New Publications and Rare Books

At this time of year, numerous reviews of new book releases appear in the literary sections of the German-language press, with major newspapers even devoting entire supplements to them. The reason for this flurry of activity is the Leipzig Book Fair. One of a librarian’s chief tasks is to decide which of these books, for example, bear sufficiently important historical witness to join a library’s collection. To mark this annual flood of new book releases, Matthias Miller, head-librarian at the Deutsche Historisches Museum, shines a light on some of the jewels of his library’s collection.

When this year’s book fair, or Buchmesse, in Leipzig opens its doors on 15 March, there will once again be thousands of newly published books gracing exhibitors’ shelves. Exhibitors will be hoping for their books to be discovered and taken home by visitors whose interest has been piqued. Many books will remain unread, a portion will be considered “niche”, and just a few – typically works of literary fiction – will become bestsellers. Reading books, whether for pleasure or as part of an academic education, is a centuries-old communication process between author and reader. The author has thoughts, which he or she then relates to the reader. Ever since the invention of the printing press and moveable type in the mid-15th century, the resulting product has served the mass-dissemination of ideas, theories, truths, and fake news. Historical watersheds such as the Reformation, the revolutions of 1848, or the student uprisings of 1968, would have been unimaginable without printed books. Books have therefore often lit the fuses for revolutions.

So often pronounced dead, the continued existence of the printed book (and the huge popularity it still enjoys throughout the world) derives from the fact that a real media revolution – analogous to the transition from clay tablet to papyrus scroll, papyrus scroll to manuscript codex, or manuscript to printed book – has not yet really taken place. After all, ebooks essentially recreate the print version via other means. Put simply, this is not a big enough shift to constitute a media revolution.

The librarian as forester

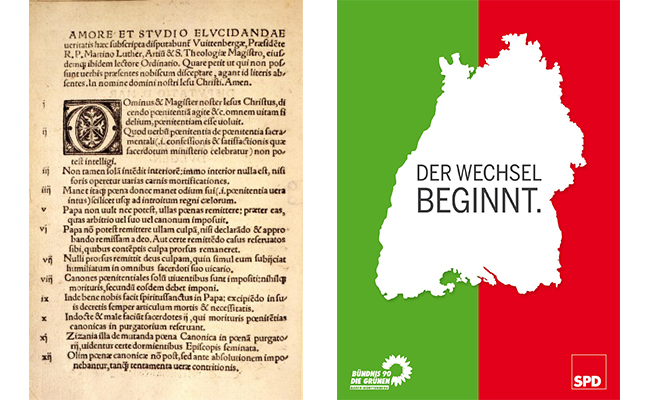

While serving as a commercial venue for touting the latest books, the fair can also be thought of as a cradle of literature in which the latest publications are launched into the world. Meanwhile, libraries have to make do with being known as the books’ resting place. Yet much of what has been produced by the printing press over the centuries only survives in libraries, and so they (alongside archives and museums) must surely be understood as repositories of knowledge and, by extension, the memory of humankind. In fulfilling this role, the library of the Deutsches Historisches Museum has a twofold mission: firstly, to acquire modern research literature on German history published throughout the world – an important resource for preparing exhibitions, curating collections, and as reference works for our affiliated specialist library for restoration. Secondly, the library acquires primary sources on German history for its Collection of Manuscripts/Old and Valuable Prints – in other words, manuscripts and printed works created contemporaneously to historical events. These might encompass anything from the first printing of Martin Luther’s “95 Theses” from 1517 (shelf mark: R 55/911.3) through to the coalition agreement in 2011 between the Greens and the SPD in Baden-Württemberg, when the Green Party won more votes than the traditional left, the Social Democrats, for the first time in state elections.

Left: “95 Theses”, Martin Luther, 1517 (R 55/911.3); Right: Coalition agreement between the Greens and the SPD in Baden-Württemberg, 2011 (Signatur: A 11/839)

Often, it is impossible to predict whether a book will attain historical significance, and in this respect the work of the librarian is like that of the forester: just as foresters will in all likelihood not be around to see the benefits of the trees they plant in 2018, books that a librarian acquires for a collection today will likely have to wait another 100 years before they are historically significant enough to be exhibited.

Anniversaries herald new publications

This year marks a number of important anniversaries. Let us take the start of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618, and the bicentenary of Karl Marx’s birth, as two such examples. In their respective periods, both events produced a plethora of publications that would today be termed “primary sources”, as they depict or reflect historical events with direct immediacy.

The Deutsches Historisches Museum’s library has 308 books printed in the period 1618–1648 alone. The rumour that the causes of the Thirty Years’ War could be traced back to the appearance of a comet in 1618 proved particularly persistent, and in 1648 a broadsheet was published, whose title translates as:

Concerning the German Thirty Years’ War, which began in anno 1618 and by the grace of God ended in anno 1648; just as God had in 1618 announced a thirty-year war with the appearance of a terrifyingly lit comet, which was visible over Europe for thirty days (shelf mark: R 92/2250).

Known today as C1618, the comet could be seen in the skies for thirty days during Advent in 1618. In the light of events that proceeded the Defenestration of Prague (the catalyst for the decades-long war), the phenomenon was not interpreted as a return of the Star of Bethlehem and the promise of salvation, but rather an as omen of looming war. This is also how Andreas Bähr, a historian of the early modern period, interprets contemporary reactions to the comet in his recently published book, “Der grausame Komet. Himmelzeichen und Weltgeschehen im Dreißigjährigen Krieg” (whose title translates as: “The Dreadful Comet: Celestial Signs and Terrestrial Events in the Thirty Years’ War”). This book will be displayed on the Rowohlt publishers’ stand at the Leipzig Book Fair, and can already be looked up at the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s library (shelf mark 18/315).

Left: Broadsheet, Von dem dreyssigjährigen Teutschen-Kriege, welcher sich Anno 1618. angefangen vnd durch Gottes Gnade Anno 1648. geendiget hat; Eben als wann Gott durch den 1618. erschröcklich leuchtenden Cometen, welcher dreyssig Tage über Europam gesehen worden, einen dreyssigjährigen Krieg verkündiget hätte …, 1648 (R 92/2250); Right: Andreas Bähr, “Der grausame Komet. Himmelzeichen und Weltgeschehen im Dreißigjährigen Krieg”, Rowohlt 2018 (18/315).

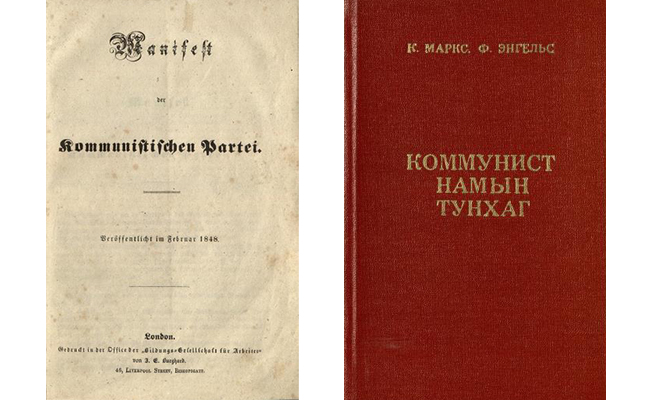

When Karl Marx was born in 1818, no one could possibly have imagined that one day he would turn the world upside down with his revolutionary writing, which for a number of decades in the 20th century divided the world into two opposing blocks. The library of the Deutsches Historisches Museum not only owns a copy of the extremely rare 1848 first edition of the “Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei” (“Manifesto of the Communist Party”), which Marx co-authored with Friedrich Engels, but also another 118 modern editions of the work in a total of 45 languages, including Mongolian and Japanese (shelf marks: 51/57<mongol. 1968> and 51/57<japan.>).

Left: Marx, Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party”, 1848 (R 92/2958); Right: Marx, Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party”, Mongol edition (51/57)

Modern biographies of Karl Marx are currently being published at a rate of nearly once a month. They include the German translation of Gareth Stedman Jones’s comprehensive study “Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion” (translated as “Karl Marx. Die Biographie”, published by S. Fischer in 2017, pp. 644), “Marx. Der Unvollendete” (“Karl Marx: The Incomplete Man”) by Jürgen Messe (Bertelsmann 2017, pp. 655), and “Karl Marx. Politik in eigener Sache” (“Karl Marx: Politics in His Own Interests”) by Wolfgang Schieder (Theiss 2018, pp. 239). You can find all these recent works at the Leipzig Book Fair and at the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s library (shelf marks 17/1673 and 17/1898).

Left: “Karl Marx. Die Biographie”, Gareth Stedman Jones, S. Fischer 2017 (17/1898); Right: “Karl Marx. Politik in eigener Sache”, Wolfgang Schieder, Theiss 2018 (in acquisition)

If you are interested in history and are looking for old and the very latest literature on past and current questions about history, then you are very welcome to come and visit the library of the Deutsches Historisches Museum! (Open Monday to Friday, 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.)