Columbus Day

On 12 October 1492, Christopher Columbus landed on the island of Guanahani (part of the present-day Bahamas). The historian Christiana Brennecke, who curated the section on European expansion in our “Europe and the Sea” exhibition, here explains why the historic date continues to be commemorated and is even celebrated as Spain’s national holiday.

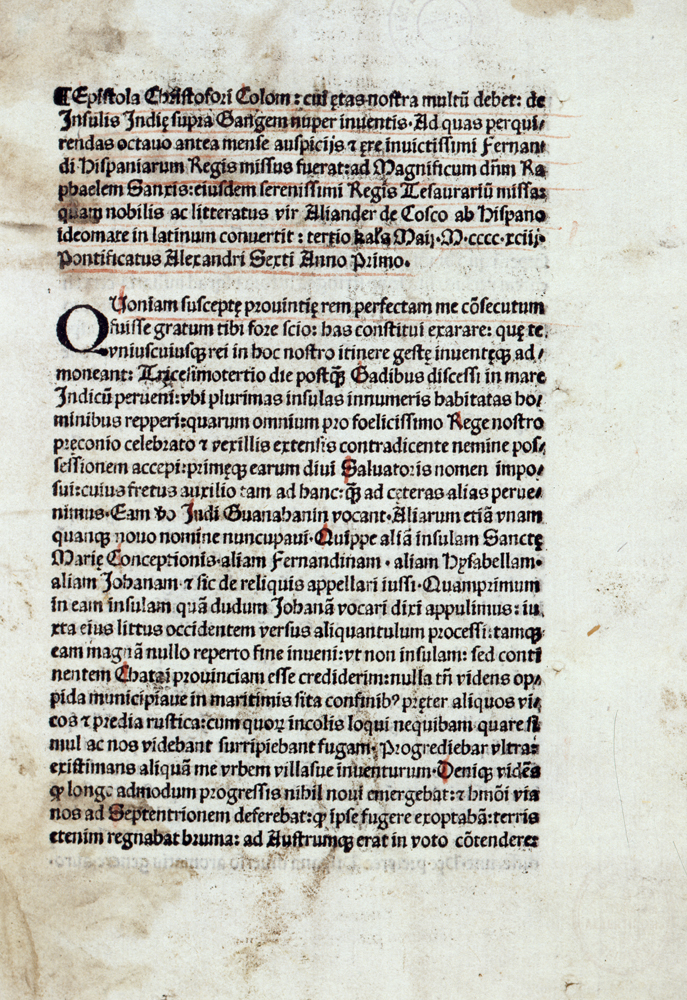

There it is, quite small and unremarkable: the first letter written by Christopher Columbus about his discoveries on the other side of the Atlantic. Originally written in Spanish, the first Latin translation of this letter (published in 1493) features in our Europe and the Sea exhibition. It marks the moment when news of the European discovery of America became public knowledge and spread with tremendous speed on the back of the thriving print trade. However, the letter contains no mention of ‘America’ or even a new continent, as, right up until his death in 1506, Columbus persisted in his belief that he had in fact landed on Asian shores. We also now know that Columbus was by no means the first person to have journeyed across the Atlantic. However, no one disputes the significance of Columbus’s first voyage or the announcement that promptly came in its wake, since news of what lay on the other side of the Atlantic proved to be an important catalyst in Europe’s continuing global expansion.

Epistola de insulis nuper inventis: Letter from Christopher Columbus to Luis de Santángel, private treasurer to King Ferdinand of Spain, after 23 April 1493, inv. no. R 53/2894, © DHM

Perceptions of 12 October 1492 through the Mirror of History

In his book Columbus and Day of Guanahani – 1492: A Turning Point in History, the historian Stefan Rinke (a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin’s Institute for Latin American Studies) traces the significance of 12 October 1492 in world history, and looks at how the event was interpreted by contemporaries and subsequent generations. The sense that 12 October 1492 heralded something ‘new’ – which, moreover, could not be easily reconciled with existing notions of the world – is evident early on in European sources. This was later vindicated, particularly after Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512) realized that the territories encountered by Columbus were in fact part of a ‘new’ continent. However, it was only over the course of the ensuing century that the events came to be understood and appraised in terms of an epochal shift. This dawning realization was closely tied up with Europe’s ongoing pursuit of territorial expansion and the far-reaching consequences of colonization. Columbus’s name initially fell into relative oblivion. It was, after all, Amerigo Vespucci who bequeathed his name to the continent. Moreover, prior to his early death, Columbus undertook three more expeditions, whose lack of success eclipsed the triumphant news of his first voyage. However, over time – and as greater access was granted to the Spanish archives – Columbus returned to public consciousness to become the global symbol of European territorial expansion in the 15th and 16th century.

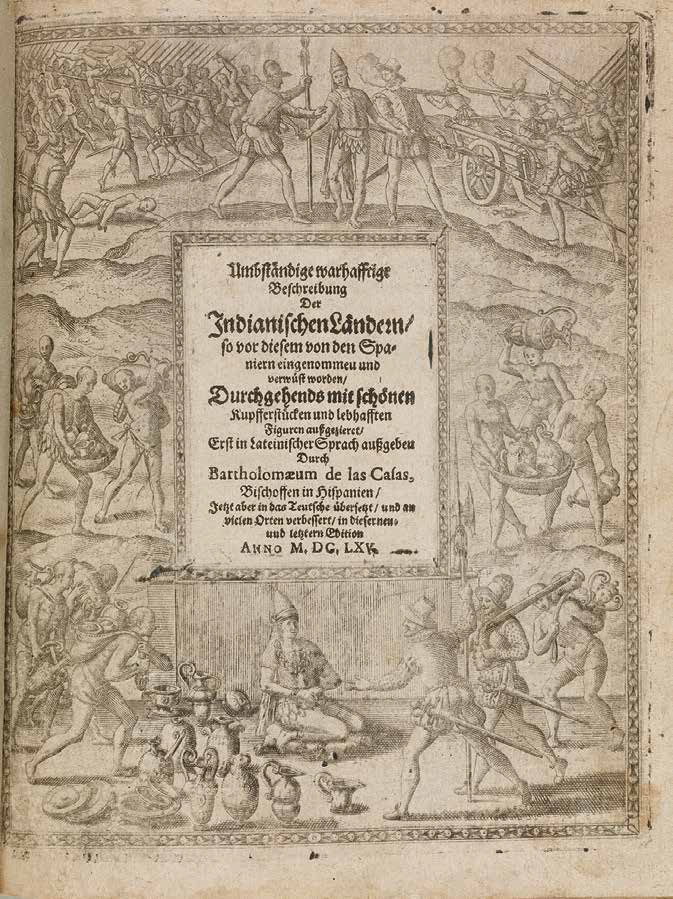

This symbolic role means that retrospective evaluations of Columbus’s personality and achievements have not only drawn on the latest developments in historical scholarship, but also the prevailing zeitgeist and political context. The United States created a new narrative and integrated Columbus into its national mythology after gaining independence from Great Britain. By contrast, the debate surrounding Columbus in Europe and Latin America became closely associated with critical perspectives on Spain’s territorial expansion. At the very latest, the publication of Bartolomé de las Casas’s visceral critique of Spanish colonialism, A Short Account of the Devastation of the Indies (Seville, 1552), marks the moment when it was no longer possible to look back at Columbus and 12 October without also considering the consequences of territorial expansion. Thereafter, interpretations that presented Columbus’s voyage as a Spanish, European, and/or Christian success story also had to contend with persistent critical voices that questioned the legitimacy of colonial expansion. However, it was some time before these criticisms were discussed extensively and in public. More recently, heated debates accompanied preparations for the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage in 1992. Critics felt that the anniversary presented a Eurocentric interpretation of events, and objected to the use of terminology such as the ‘discovery’ of America.

Bartolomé de Las Casas: Heidelberg, 1665, R55/4087.2 © DHM

Columbus Day, Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Fiesta Nacional de España – commemorations now celebrated on 12 October

Still today, shifting interpretations of 12 October 1492 continue to be reflected in the different names given to the associated commemorations. In the USA, where 12 October has been celebrated as Columbus Day since the early 20th century, the date is known in some areas as Indigenous Peoples’ Day: a reminder of the rights of indigenous peoples, for whom 12 October 1492 heralded oppression or even wholesale elimination. In Central and South America, meanwhile, the date was given a variety of different names. From the early 21st century, the date known as the ‘Day of Race’ (Día de la Raza) became the ‘Day of the Encounter between Two Worlds (Día del Encuentro de Dos Mundos), the ‘Day of Indigenous Resistance’ (Día de la Resistencia Indígena), or the ‘Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity’ (Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural) – to list just a few of the commemorations celebrated on 12 October.

So what about Spain? The former colonial power, under whose flag Columbus set sail in 1492, has adopted a more nuanced approach to its history in recent years. Nevertheless, even today, 12 October is charged with such significance for the country’s monarchy that it is celebrated as Spain’s national holiday (Fiesta Nacional de España). Here too, the date was for many years celebrated as the ‘Day of Race’ or ‘Day of Hispanic Culture’ (Día de la Hispanidad), which served to stress the country’s shared roots with the independent nations that once formed part of its empire. It was then renamed and declared Spain’s national holiday by virtue of a law passed on 7 October 1987. The choice was based, of course, on 12 October’s significance as a historical anniversary – albeit understood from a purely Spanish perspective and without dwelling on the serious consequences of colonial expansion. Instead, 12 October 1492 here signifies in a rather roundabout manner the moment at which the emergent Spanish national state embarked on a process of projecting its language and culture far beyond its European shores.