Moses before Moses

Stefan Moses was one of the great photographers of the Federal Republic. Germany and the Germans remained his main subject to the end of his life. Our exhibition “The Exotic Country. Photo reportages by Stefan Moses” follows his career. Prof. Dr. Christoph Stölzl, president of the Franz Liszt academy of music in Weimar and founding director of the Deutsches Historisches Museum, describes in his opening speech of the exhibition, excerpts of which we are publishing here, the career of Stefan Moses before he became the most famous photo chronicler of the Federal Republic.

In 1928 Stefan Moses was born into a well-educated, middle-class family in Liegnitz, Silesia. The Jewish background on the side of his father’s family, who had long since distanced themselves from any form of religious orthodoxy, soon led to the inescapable fate of isolation, persecution and in the end mortal danger. Part of the Moses family and many friends and acquaintances took the path of emigration. After the shock of the November pogrom, mother and son moved from Liegnitz to the purportedly safer, because anonymous city of Breslau. But there, in 1944, the state authorities intervened. Moses landed in the Ostlinde forced labour camp and came within an inch of being crushed in the jaws of terror. But by a stroke of luck amidst his misfortune Stefan managed to flee from the camp in February 1945. In the summer of that year we find him with his mother, swept by the waves of destiny from East to West, in Jena. Here he completed his training in photography with Grete Bodlée, a photographer of children.

Youngest theatre photographer in Germany

From 1947 to 1949 Moses was the youngest theatre photographer in Germany, working at the National Theatre in Weimar, and was thus involved in the pan-German re-emergence of theatre life. As a photographer Stefan Moses had begun working with children, himself still half a child in those dark times. Now for three years the magic world of theatre became his aesthetic laboratory. And he experienced the transformation of his familiar actor colleagues into their roles, which sometimes acted as masks.

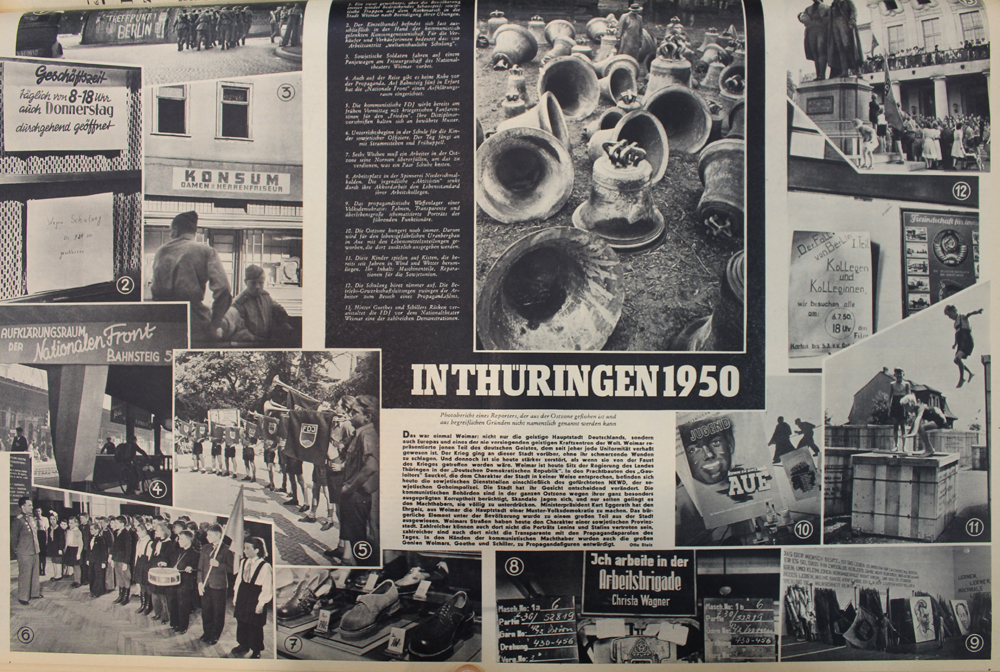

The Weimar years are also the time when Moses took his first steps as a photo reporter and photo chronicler. He often captured scenes that did not fit into the required optimistic picture of communism. His irrepressible curiosity for the everyday, the average and for different physiognomies can already be felt here. A talent for the human image begins to take its first cautious steps at this time.

In the year 1950, when after the founding of the GDR the SED began tightening the reins of state control of art, Moses sensed that he would not be able to breathe freely in the “worker and peasant state”. And so he undertook the leap into the West, to Munich. It almost took the form of a farewell to Germany – understandable after what he had gone through as a child. In Munich two visas for Chicago had already been prepared, procured by a helpful uncle who had emigrated earlier. But his uncle waited in vain.

“… it was impossible for me to leave this Germany that I had hardly really begun to know.”

An instinct whispered to him to stay in order to take pictures of the people who, like him, had survived the war. He wanted to be in Germany, and only here, when the new age began, “full of anticipation and hope for new freedoms, new life, democracy and new luck. [I was] terrifically curious about all that was coming […], the incalculable future where you would sail with the rapidly floating clouds, with pictures in your mind and a Leica in your hand.”

“The good Lord sent me to Munich”

Moses’s first photo stories were published in Munich in the weekend supplements of the Neue Zeitung, a newspaper founded by the American occupation forces and devoted to re-education, the building of a liberal, cosmopolitan Germany. It was the ideal starting point for a young photographer with boundless desire to discover people and talents.

Wochenendbeilage der Neuen Zeitung, 26. August 1950

Between 1950 and 1960 Moses worked as a photo reporter for the magazines of the Kindler publishing house, Das Schöne and Revue, which like the magazine stern that was founded around the same time, emulated the leading American model, Life magazine, which for its part had largely been created by Jewish photographers that had been driven out of Germany after 1933. The years before television brought the magazines huge circulations, many pages of advertisements, and the role of an influential forum for political discourse.

Kindler sent the young Moses in the 1950s first to New York and then on an extensive trip though Europe which he undertook with the young author and actor Walter Rilla, who had been living in exile in England. The result of this exploration of faces, gestures, conditions, landscapes and architectures was a book with the title from a Goethe quotation from the prologue to Faust: “Herrlich wie am ersten Tag” (Fair as on the primal day) – a visual plaidoyer for the indestructability of European humanity, irregardless of the different political conditions in East and West, South and North. And then came 1956: the bloody uprising in Hungary that shook all of Europe. Moses captured the eerie scenes of the bitterly sombre Budapest autumn.

In the genius troop of stern

In 1960 editor-in-chief Henri Nannen brought Moses from Munich to stern. This ushered in the legendary heyday of German “human touch” photography – photo journalism as a “moral institution”. At stern Moses experienced the “exciting, delightful, young years with new people, new languages and new freedoms. No one could or wanted to stop us from formulating the global language of photography in a more intelligent way in our pictures. We were now the new ‘image makers’. These were productive years. We experienced an atmosphere of renewal. In 1960 we could already hear the hopeful sixties rolling in.”

The stern of the 1950s and 1960s was famous for its reportages from around the world. But in the case of Moses, who was there from the beginning – in Israel, for example, where he met relatives who had emigrated, or in South America – the viewpoint changed: the more he got to know about the exotic lands abroad, the more he became conscious of the fact that his terra incognita was not far afield, but rather very close by: Germany became for him, as he once expressed it, the “most exotic country”. He became more and more fascinated with the Janus-faced homeland that had shown him the hideous face of terror in his youth and was now putting on a demonstratively harmless face as it pottered around with its “economic miracle”. In retrospect he remarked that Germany for him was “just as exotic as Caracas, Kathmandu or the Congo, full of unexplored places.” On a trip to England for stern, which was to yield a survey of the state of British society, the idea was born to create a large-scale visual sociology of the Germans.

The most exotic country in the world

In the seamless progression of stern commissions for reportages on, for example, the different nuances of religion in Germany, on German festivities from the popular “monster carnival” (Thomas Mann) of the Munich Oktoberfest to the elitist-conspiratorial cult site of Bayreuth, on the Biotop Bonn, on the associations and clubs of Germans in their regions, on duelling students’ societies or even on skat players, the idea gradually took shape to put together a careful study of the Germans, systematically planned as a long-term work with portraits staged in alternating dramaturgical concepts. What were the post-war faces now like, the faces he clearly remembered from pre-war times and the war? Their shapes, their attire, their postures?

From 1962 to 1964 Stefan Moses travelled through the Federal Republic and sought out people who with their features, their bearing, their clothing could tell an entire story without words. At the end of his strenuous tour he brought back an extensive panorama of the West Germans such as no one since the legendary undertaking of August Sander in the 1920s had succeeded in doing. Those were the climactic years of the feeling of an “economic miracle”. What an immense effort the re-emergence of the West German half of the nation had cost can be seen – despite the occasional smiles – in the deeply earnest faces of the people who revealed their personality to Moses. A decade later the Federal Republic had changed radically in the wake of the ’68 cultural revolution. Moses’s “Germans” are a last look at the real “post-war society”.

Moses and the grey cloth

The basic idea behind Moses’s concept was to slip into the seemingly anachronistic role of a 19th century travelling photographer. Instead of using a studio he had a large grey felt cloth as a background, which allowed him to create a new, private, quasi magically defined space wherever he went. Wherever a face or work clothes fascinated him he simply hung up the cloth and invited the people to stand before the camera. He came upon them on the street and at carnivals, in factory halls or cemeteries, in offices and restaurants, at railway stations and churches. And a miracle happened: from one moment to the next inconspicuous “average people” were turned into unique individuals. Every person, be their function in society ever so marginal, gained the inalienable dignity that had recently become the central promise of the West German constitution. It was perhaps the first time that someone had convincingly underlined this constitutional pledge.

Emigrants

It is not surprising that the subject of emigration winds through the work of Stefan Moses like a silver thread. For herein come together the continuity and disruptions of German history, but also the fate of German Jewry in an exemplary way. The fate of his own family was also closely linked to the topic. Already in 1949, as theatre photographer in Weimar, he had photographed Thomas and Katja Mann, who had returned to Germany on the occasion of the Goethe anniversary celebration. From these first portraits of emigrants until the last ones he took in the year 2003 it was the people who had been forced to leave Germany after 1933 for whom Moses felt empathy stemming from his own biography. He had been able to reach 99 prominent personages, but had missed many others he had wanted to portray: they were spread throughout the world, while others had died too soon. Moses calls his emigrant portraits “something like the lost continent of Atlantis”. At the same time he is conscious of the fact that some irretrievable factor disappeared with these faces: German destinies as dramatic, tragic and heroic as will never again come to pass.

Ephemerality and humanity

In our short life one can only engage oneself for one thing, Moses once remarked. He chose to explore the most interesting thing: his immediate surroundings, his “homeland” Germany. The longer this second component of the work of Stefan Moses, the major portraits, is present in the world, the clearer it becomes that they have little to do with traditional “documentarism”. His Germans are likenesses and images of potentialities at the same time. Thus they live from the chameleon-like ambiguity of photography, which since its invention has been many things at the same time and in varying amalgamations: document and artwork, diary and epos, elusiveness and consolidation, reality and semblance, monument and demontage, convention and surprise – this is, to be brief, perhaps the best method of tracking down the unfathomable secret of that which is human.

|

Prof. Dr. Christoph StölzlProf. Dr. Christoph Stölzl is one of the most prominent German cultural historians. Born in Bavaria in 1944, he began his career with research on the history of European national movements. In 1987 he became founding director of the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin and in 1991 opened the first exhibition of the museum in the Zeughaus with portraits that Stefan Moses had made of people in the GDR during the dramatic events of 1989/90. Since 2010 he has been president of the Franz Liszt academy of music in Weimar. |