Fred Stein and the “Pariser Tageblatt” Affair

Ulrike Kuschel | 9 June 2021

Fred Stein began in 1934 to work as a portrait and press photographer in Paris. The curator of the exhibition “Report from Exile – Photographs by Fred Stein”, Ulrike Kuschel, sheds light on Stein’s membership in the Association of German Journalists in Emigration within the context of the “Pariser Tageblatt” affair.

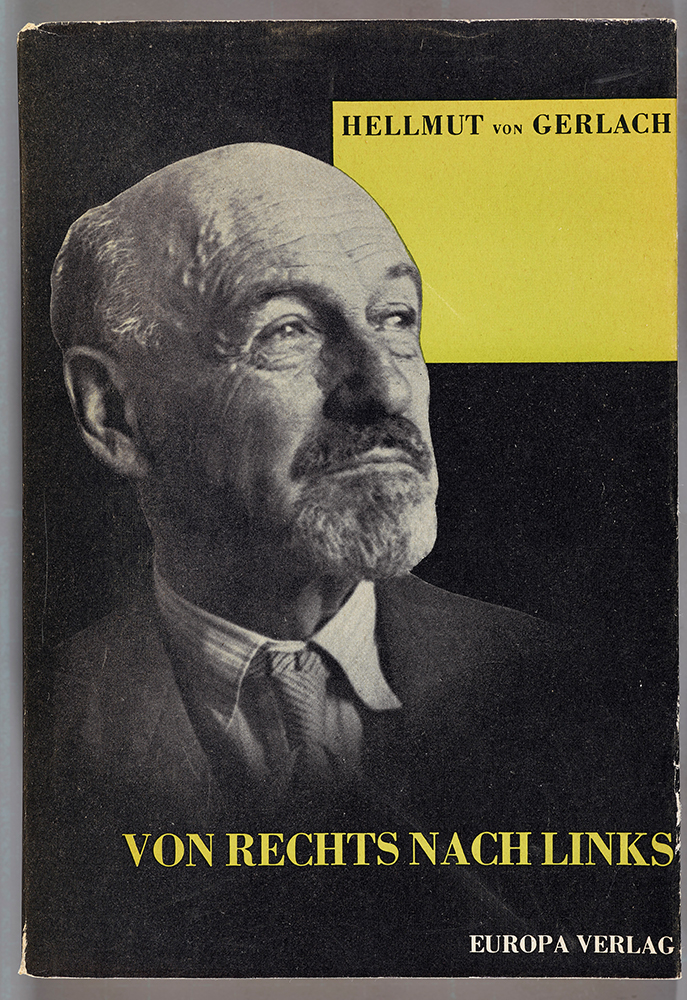

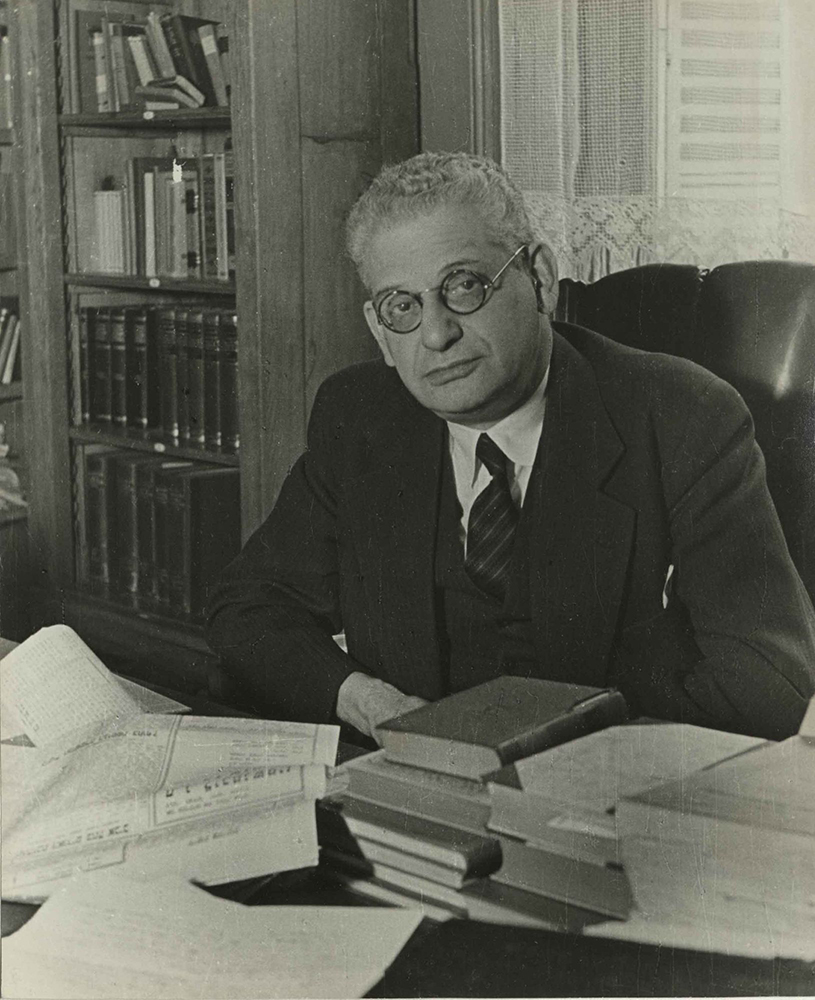

In 1935, the “Press photographer Alfred Stein” was unanimously accepted, together with four other colleagues, as a member of the Association des Journalistes Allemands Émigrés (Association of German Journalists in Emigration), as the undated protocol of a meeting of the executive board notes.[i] The members of the association who were responsible for approving new applications for membership included, alongside Georg Bernhard (1875–1944), chairman of the board, one of the most eminent economic journalists of the Weimar Republic and editor-in-chief of the “Pariser Tageblatt”; Leopold Schwarzschild (1891–1950), publisher of the “Neues Tage-Buch”; the art critic Paul Westheim (1886–1963); the publicist and politician Hellmut von Gerlach (1866–1935); and the journalist Milly Zirker (1888–1971).

Hellmut von Gerlach: Von Rechts nach Links, Europa-Verlag Zürich, 1937. The photo on the book jacket is one of the portraits made by Fred Stein © DHM, Photo: Indra Desnica

Fred Stein probably had many different reasons for joining the Association of German Journalists in Emigration. In his mid-twenties, he had given as the primary reason for fleeing Germany that he was politically endangered;[ii] in exile he wanted to continue his political engagement and participated, for example, in the activities of the “Anti-Hitler Youth”.[iii] Moreover, the journalists’ association, whose members Bernhard, Kurt Caro, Richard Dyck, Hans Jacob and Erich Kaiser made up almost the entire staff of the later founded “Pariser Tageszeitung”, gave him access to a circle that included many prominent journalists, intellectuals and writers – an important step for the young, self-taught photographer, who needed to have contact with the press. Not least of all, the association helped to cope with elementary personal problems that confronted the often stateless and penniless refugees, such as by donating clothes or helping to acquire identification papers.

In November 1935, Stein requested support from Georg Bernhard and Milly Zirker, who had belonged to the intimate circle of the “Weltbühne”, published by Carl von Ossietzky. Stein wanted to join the “international journalist organisation”[iv] as well as the Association Professionnelle de la Presse Étrangère en France, because, as he wrote, “for my jobs at current occasions I am almost handicapped without the necessary credentials.”[v] Bernhard thereupon wrote to the Fédération internationale des journalistes, of which he had been chairman for a time:[vi] “M. Stein, journalist and member of our organisation, has the honour of requesting you herewith to confirm his status as a journalist. He needs it for the renewal of his identification card.” [vii] Bernhard also offered to sponsor Stein’s application to the Association Professionnelle der la Presse Étrangère.[viii]

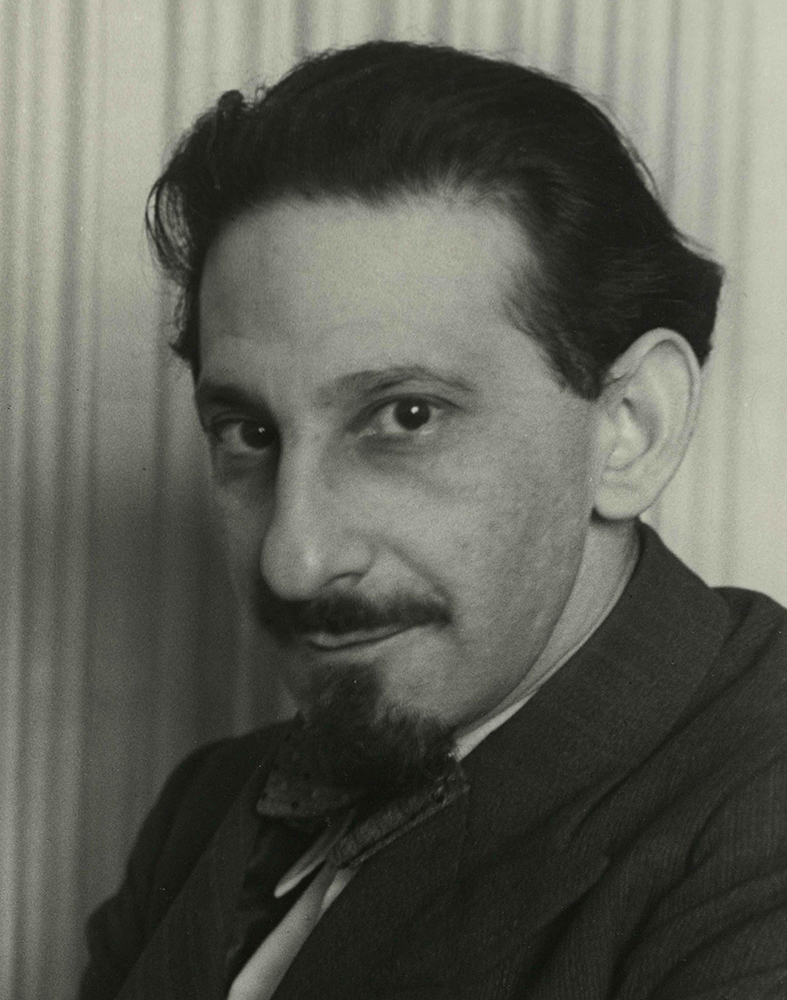

Georg Bernhard, Paris, 1936, Frankfurt am Main, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, EB autograph 1009 © Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

The fact that Stein listed Milly Zirker as a reference in a questionnaire for recognition as a refugee in 1936[ix] is further evidence of the long-lasting, not only professional support he received from the Association of German Journalists in Emigration and its board members.

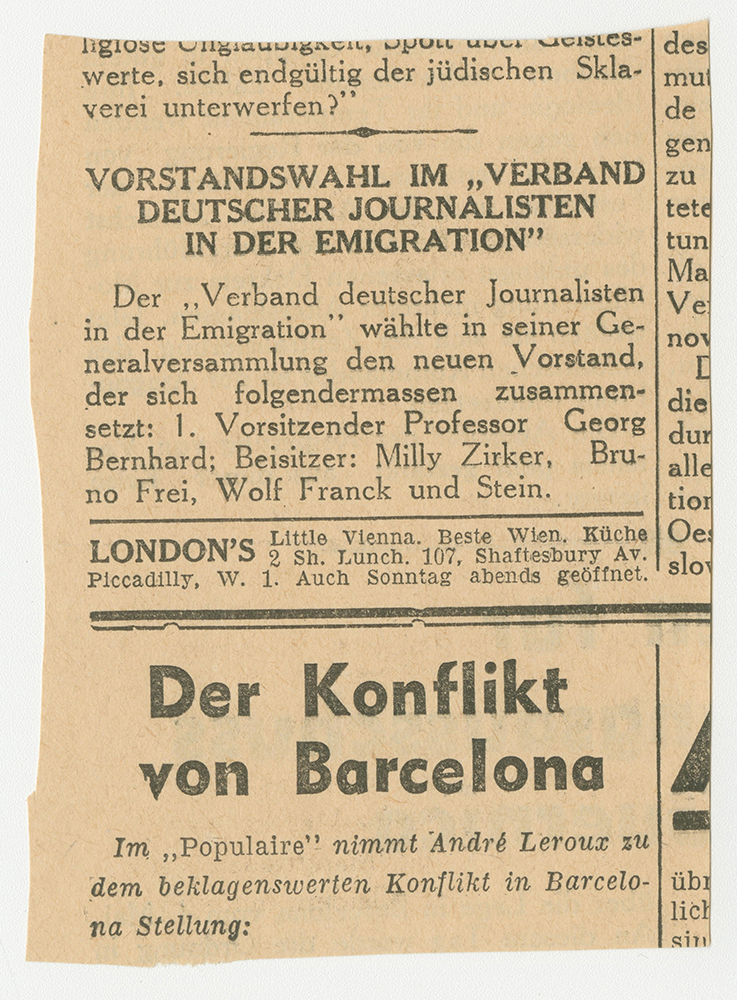

Only a year and a half later, in May 1937, Stein was elected to the journalists’ new executive board, as is documented in an article in the “Pariser Tageszeitung” headlined “Board member election in the ‘Association of German Journalists in Emigration’”.[x] However, the seemingly insignificant announcement found in the estate of the writer Maximilian Scheer, himself a member of the Association of German Journalists in Emigration, raises new questions. How did it happen that Stein, a 28-year-old photographer, was elected to the board? There is reason to believe that he first decided to run for the post after the old board came under pressure due to the “Pariser Tageblatt” affair and called for a new election.

Pariser Tageszeitung, 7 May 1937, p. 2 © Berlin, Akademie der Künste, Maximilian-Scheer-Archiv, Maximilian Scheer 1130

What was the “Pariser Tageblatt” affair about, this “German exile scandal par excellence”?[xi]

The “Pariser Tageblatt”, the longest-running daily newspaper of the German-language exile scene, was founded in December 1933 in Paris. In the first issue, editor-in-chief Georg Bernhard guaranteed with his “life achievement” for the fundamental democratic convictions of the newspaper and formulated the claim “[not to be] an ‘emigrant paper’, but rather a newspaper for all Germans […] who live outside of the power sphere of the Third Reich and do not want to relinquish their right to think whatever they want.”[xii] However, between the publisher, Vladimir Poliakoff,[xiii] a Russian businessman, and the editorial staff under Georg Bernhard, it came to differences in the view of the paper’s orientation. In the fight against the mutual adversary, the editors were willing to work together with other emigrant groups and organisations who did not necessarily share their liberal and democratic position.[xiv] In 1936 the editorial staff decided to part with their politically more moderate publisher, who opposed this cooperation. In a “statement” in the “Pariser Tageblatt”, it was claimed that Poliakoff had negotiated with the head of the press and propaganda department of the German Embassy in Paris and wanted the newspaper to “assume a more loyal position towards Hitler and his endeavours.”[xv] In order to “prevent the successful outcome of the coup by the Hitler propaganda office”,[xvi] the editors took over the newspaper, which they published as of 12 June 1936 under the new name “Pariser Tageszeitung”. Poliakoff’s attempts to continue the “Pariser Tageblatt” with a new editorial staff were successfully thwarted.

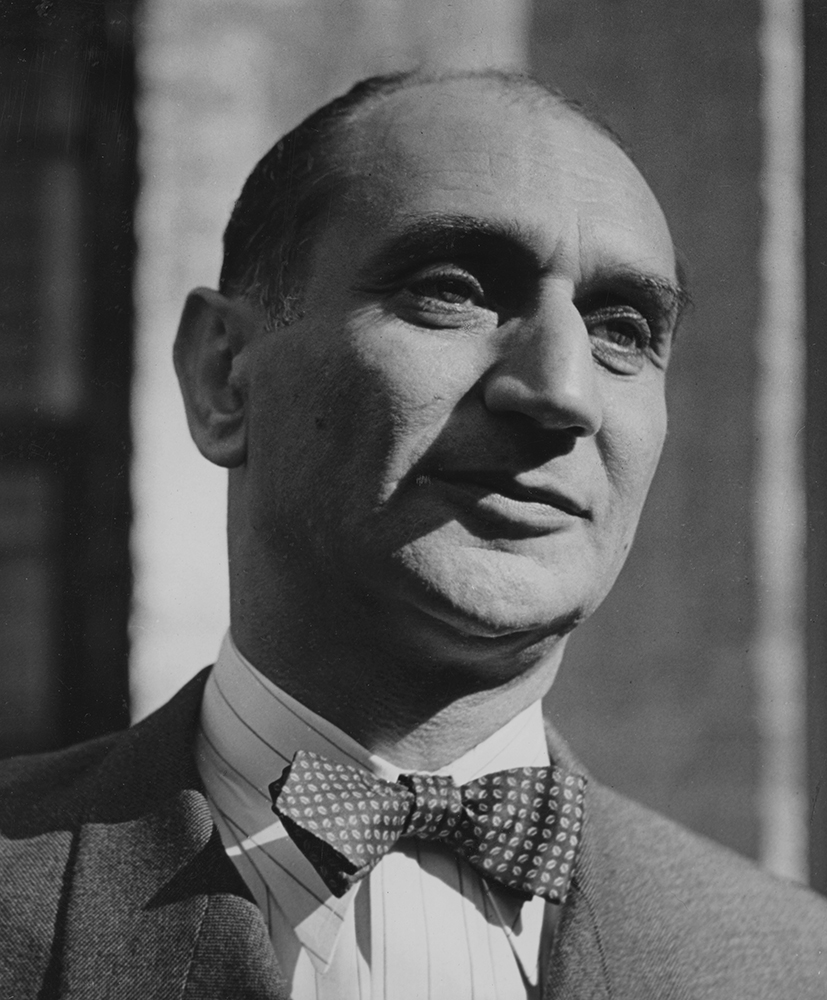

Shortly thereafter, Leopold Schwarzschild wrote an article in the “Neues Tage-Buch” accusing Bernhard, a fellow board member of the journalists’ association, and the newspaper’s editor Kurt Caro of having launched “knowingly false”[xvii] and unsubstantiated accusations against the publisher Poliakoff, whom he thus attempted to exonerate. Thereupon, Bernhard and Caro for their part accused Schwarzschild of trying to slander them. At a general assembly meeting of the Association of German Journalists in Emigration at the end of July 1936, a “commission for the examination of the Poliakoff – Pariser Tageblatt matter” was appointed in order to clear up the repeated accusations and allegations,[xviii] which no doubt partly stemmed from personal animosities. After 20 meetings, each lasting several hours,[xix] the opinions of the five commission members were still so far apart that two separate final reports were issued. The report of the majority “in the matter of Bernhard–Schwarzschild and Schwarzschild–Bernhard”, written by Ruth Fischer, Arkadi Maslow and Robert Breuer for the Bernhard side, came to the conclusion that the Bernhard party, represented by the editorial staff of the “Pariser Tageblatt”, had acted “in good faith when they broke off relations with Poliakoff and founded […] the new newspaper.”[xx] The report of the majority was published in March 1937 in the “Pariser Tageszeitung” and ended with the assessment that the matter had “caused a great deal of bad blood in certain circles of the German emigrants” and that “this effect could have been avoided.”[xxi]

Editor-in-chief Bernhard triumphed: “I can understand that Herr Schwarzschild will not be very pleased with the verdict.”[xxii]

Leopold Schwarzschild, New York, 1942 © Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

The “Report of the minority of the investigative commission in the dispute Bernhard–Caro on the one hand and Schwarzschild on the other for the Association des Journalistes Allemands Émigrés”, written by Paul Dreyfus (1880–1940), a writer and lawyer, and the pacifist Berthold Jacob (1898–1944), arrived at the opposite conclusion. Berthold and Dreyfus, representing the Schwarzschild party, judged that it had been a “deliberate” act by “Messieurs Bernhard and Caro” with the aim of ousting Poliakoff in order to install a different publisher. “It is a matter of a fight between capitalists, carried out from the one side with the means of ‘miscarriage of capital’ through libel.”[xxiii] This report, written in February 1937, was of course not published in the “Pariser Tageszeitung”.

Berthold Jacob, Paris, 1936, Frankfurt am Main, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, EB autograph 1062 © Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

In May 1937, an election of board members of the Association of German Journalists in Emigration took place, in which Bernhard, confirmed in his office of First Chairman, apparently emerged in a stronger position. The new board, however, could not be compared with that of 1935. Alongside former members Bernhard and Zinker, there were now considerably younger and less substantial members: the communist Bruno Frei (1897–1988), Wolf Franck (1902–1966), who was also a board member of the “Schutzverband Deutscher Schriftsteller” (SDS, Association for the Defence of German Writers),[xxiv] as well as Fred Stein, at age 28 the youngest. At its session at the end of May, the new board had to acknowledge that 13 members had resigned from the association,[xxv] including Leopold Schwarzschild, Berthold Jacob and Paul Dreyfus, who by quitting – according to the description in the “Pariser Tageszeitung” – “had made it impossible to carry out the pending expulsion proceedings against them.”[xxvi] At the same time, the board announced that they had entered into an agreement with the German Freedom Library run by Alfred Kantorowicz and other communist writers and journalists.

This, however, was not the end of the affair, which has still not been entirely resolved and which Lion Feuchtwanger immortalised in his novel “Exil” (1940). In July 1938, Bernhard was sentenced to a punitive fine in a defamation trial which Poliakoff had brought against him, and the “Pariser Tageszeitung” was ordered to publish the court decision. In the newspaper edition of 24 December 1938, the decision, under the headline “On the conclusion of the conflict”, was preceded by a “statement”. In it the publisher and editorial staff, from which Bernhard had retired in January 1938,[xxvii] informed the readers that they had come to the conclusion that Poliakoff “had been wronged” and that the attacks against him were “sincerely to be regretted”.[xxviii]

The executive board of the Association of German Journalists in Emigration objected to this statement. In a proposed resolution, the board, still under the chairmanship of Bernhard, called the statement a “gross deception of the public”[xxix] and stressed that they would “completely adhere to their decisions insofar as they concern the person of Prof. Georg Bernhard, which the last general assembly had confirmed by re-electing him chairman.”[xxx] However, Fred Stein rejected the resolution, with the exception of the cited last paragraph, because it “created the impression that Prof. Bernhard was in the right and Mr Poliakoff was at fault” and criticised that the resolution was not suitable “to promote the development of the association, on the contrary.”[xxxi]

Milly Zirker, 1944 © Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

Milly Zirker then sent Stein an emended, less confrontational version.[xxxii] Zirker’s hope that Stein would now approve the resolution, which the board did not plan to publish at that time,[xxxiii] was apparently not fulfilled. Stein found “no cause” to change his standpoint[xxxiv] and thus took a clear position against continuing the conflict. At all events, the carefully formulated resolutions and letters evidently concealed the vigorously waged discussions. In 1965, Stein recalled that he had already had “a confrontation with Milly Zirker in Paris before the outbreak of the war” and had wanted to step down from his functions in the journalists’ association.[xxxv] Stein, who had quite possibly joined the board of the Association of German Journalists in Emigration out of a feeling of loyalty, had had to endure the bitter experience in Paris “that the cooperation with communists in German organisations had become a farce (cultural cartel, journalists’ association, SDS, youth).”[xxxvi]

In the USA, Stein, who had been politically active since his youth, refrained from further political activities[xxxvii] but remained in contact with former colleagues from the journalists’ association, of which not only his New York portraits provide evidence. In 1943, Bernhard, whom Stein had photographed in his study in 1941, again wrote a reference for him. In it Bernhard confirmed Stein’s membership in the Association of German Journalists in Emigration and recommended him “as a good photographer”.[xxxviii]

Fred Stein, around 1961 © Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

Sources

[i] Protocol of a meeting of the board, no date (before 1 August 1935), Bundesarchiv R/8052/1, Bl.19.

[ii] Questionnaire on an application for recognition as a refugee, “Circumstances of the emigration”, 30 December 1936, Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris. Stein, who began early on to participate in socialist youth organisations, had been a member of the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP) since 1931.

[iii] Letter from Fred Stein to Georg Bernhard, 30 November 1935, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 50

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Michaela Enderle-Ristori: Markt und intellektuelles Kräftefeld: Literaturkritik im Feuilleton von „Pariser Tageblatt“ und „Pariser Tageszeitung“ (1933–1940), De Gruyter, 1997, p. 16 https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbkk4gq (accessed 19 May 2021)

[vii] “M. Stein, journaliste et membre de notre organisation, a l’honneur de vous demander par la présente de bien vouloir lui certifier sa qualité de journaliste. Il en a besoin pour le renouvellement de sa Carte d’Identité.“ Letter from the Association des Journalistes Allemands Émigrés (Georg Bernhard, Milly Zirker) to the Fédération Internationale des Journalistes (Mme. Peladan) from 18 December 1935, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 (?), German translation by Ulrike Kuschel

[viii] Letter from Georg Bernhard to Fred Stein, 2. (?) Dezember 1935, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 62

[ix] Questionnaire on an application for recognition as a refugee, “IV. Circumstances of the emigration to France”, 30 December 1936, Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris

[x] Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 2, No. 329, 7 May 1937, p. 2

[xi] Walter F. Peterson: Das Dilemma linksliberaler deutscher Journalisten im Exil. Der Fall des Pariser Tageblatts. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Jahrgang 32 (1984), Heft 2, p. 281

[xii] Pariser Tageblatt, Vol. 1, No. 1, 12 December 1933, p. 1

[xiii] Also: Vladimir Poliakoff/Poliakov /Poljakoff/Poljakow

[xiv] Walter F. Peterson: Das Dilemma linksliberaler deutscher Journalisten im Exil. Der Fall des Pariser Tageblatts. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Jahrgang 32 (1984), Heft 2, p. 288

[xv] Pariser Tageblatt, Vol. 4, No. 911, 11 June 1936, p. 1

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] „An Leopold Schwarzschild“ (“To Leopold Schwarzschild”), rejoinder by Manuel Humbert (Kurt Caro) in: Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 1, No. 28, 9 July 1936, p. 1

[xviii] „Bericht der Minderheit der Untersuchungskommission in der Streitsache Bernhard – Caro einerseits, Schwarzschild andererseits: für die Association des Journalistes Allemands Emigrés“, Paris : Association des Journalistes Allemands Émigrés, 26 February 1937. Author: Paul Dreyfus, Deutsches Exilarchiv: EB 61b/2 https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2990789 (accessed 19 May 2021)

[xix] Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 2, No. 266, 4 March 1937, p. 3

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Ibid. p. 4

[xxii] Ibid. p. 1

[xxiii] Paul Dreyfus, Berthold Jacob: „Bericht der Minderheit der Untersuchungskommission in der Streitsache Bernhard – Caro einerseits, Schwarzschild andererseits für die Association des Journalistes Allemands Emigrés“, Paris, 26 February 1937, p. 43 https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2990789 (accessed 20 May 2021)

[xxiv] Letter from Wolf Franck to Rudolf Leonhard, Paris, 17 March 1937, Berlin, Akademie der Künste, Maximilian-Scheer-Archiv, Maximilian Scheer 1395

[xxv] Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 2, No. 352, 30 May 1937, p. 2

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 3, No. 875, 24 December 1938, p. 3

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] As justification, it was stated that shortly before publication of the statement, two editors “had been ousted and that the permanent advisor to Poliakoff had joined the editorial staff”. Cf. Proposed resolution of 29 December 1938, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 117

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Statement by Fred Stein, no date (after 29 December 1938), Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 116 (front side)

[xxxii] Deleted from the formulation “Statement […], in which a stand is taken against Prof. Bernhard and for Poliakoff” were the words “and for Poliakoff”. Cf. Proposed resolution from 29 December 1938, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 117, and resolution of 4 January 1939, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 118

[xxxiii] Letter from Milly Zirker to Fred Stein, 5 January 1939, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 104

[xxxiv] Letter from Fred Stein to Milly Zirker, 15 January 1939, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R/8052/4 Bl. 116 (back side)

[xxxv] Letter from Fred Stein to Julius Epstein, 6 September 1965, Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Ibid.: „… für die gebrannten Kinder, zu denen ich gehöre, [ist] nichts mehr übrig geblieben als ‚Friends of German Labor‘ und kulturelle Arbeit wie ein Deutsch-Sprachiges Forum und Teilnahme an Goethe House etc.“ (“… for children who had once been hurt, to which I belong, [there is] nothing left except ‘Friends of German Labor’ and cultural work such as a German-language forum and participation in the Goethe House etc.”

[xxxviii] Georg Bernhard, To whom it may concern, 13 February 1943, Fred Stein Archive, Stanfordville, NY