New U-Bahn stop takes you straight to the Museum

Sabine Witt | 9 July 2021

With the opening of the new U-Bahn station Museumsinsel on the U5 line, you will now travel quickly to the Museum Island in Berlin-Mitte, the heart of Berlin’s art and culture. The north exit of the metro station is right in front of the DHM’s Zeughaus. Based on objects in our collections, Sabine Witt, head of the DHM Everyday Culture collection, sheds light on the eventful history of the Berlin U-Bahn network below and above the asphalt.

The metro line U5 connects Hauptbahnhof, Berlin’s main station near the government quarter, with the traffic hub Alexanderplatz and districts further eastwards. On the one hand, it stands in a certain tradition of Berlin transport history, and yet it is also a brand-new phenomenon. 125 years ago, in autumn 1896, the ground-breaking ceremony for the Berlin elevated and underground train network took place, and in 1902, after six years of construction, the first trains rolled along the main line (now U1). That laid the cornerstone for a network which then connected the city and circle lines, which had been in operation since 1882, with the terminus and long-distance stations on the edge of the city centre.

Mobility for the young metropolis

The rapid population growth in the German Empire had turned Berlin, around 1900, into a metropolis with approx. 1.8 million inhabitants. The electric engine developed by Werner von Siemens made it possible from 1879 to manufacture electrical locomotives and thus to build up an efficient transportation system that could handle the local public traffic needs of the big city.

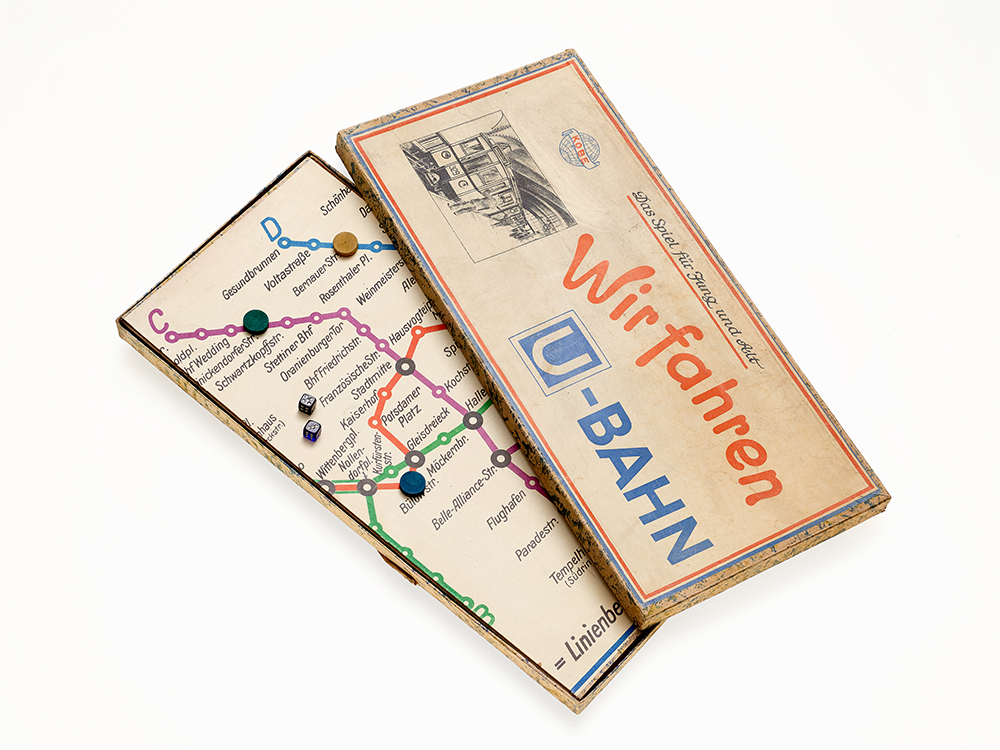

Board game „Wir fahren U-Bahn“, around 1930. Inv.-Nr. AK 93/790 © DHM

From the ground-level railway to the underground

The main line metro trains travelled above ground from the city station Warschauer Strasse over the bridge Oberbaumbrücke to Schlesisches Tor and Görlitzer Bahnhof, leading further westwards past Kottbusser Tor and Hallesches Tor to Nollendorfplatz. The negotiations with Charlottenburg, then an independent city, about continuing the line to the city railway station Zoologischer Garten and beyond proved to be difficult. For reasons of urban planning, Charlottenburg rejected the idea of building an above-ground railway on viaducts, so that the route from Nollendorfplatz had to be built as an underground railway. The counterarguments in Berlin at the time were based on the same structural challenges the city faces today: a high ground-water level, a complex substratum, running sand, as well as a certain competition within the urban infrastructure about the space available under the ground: the Berlin canalisation network had been completed only a short time earlier.

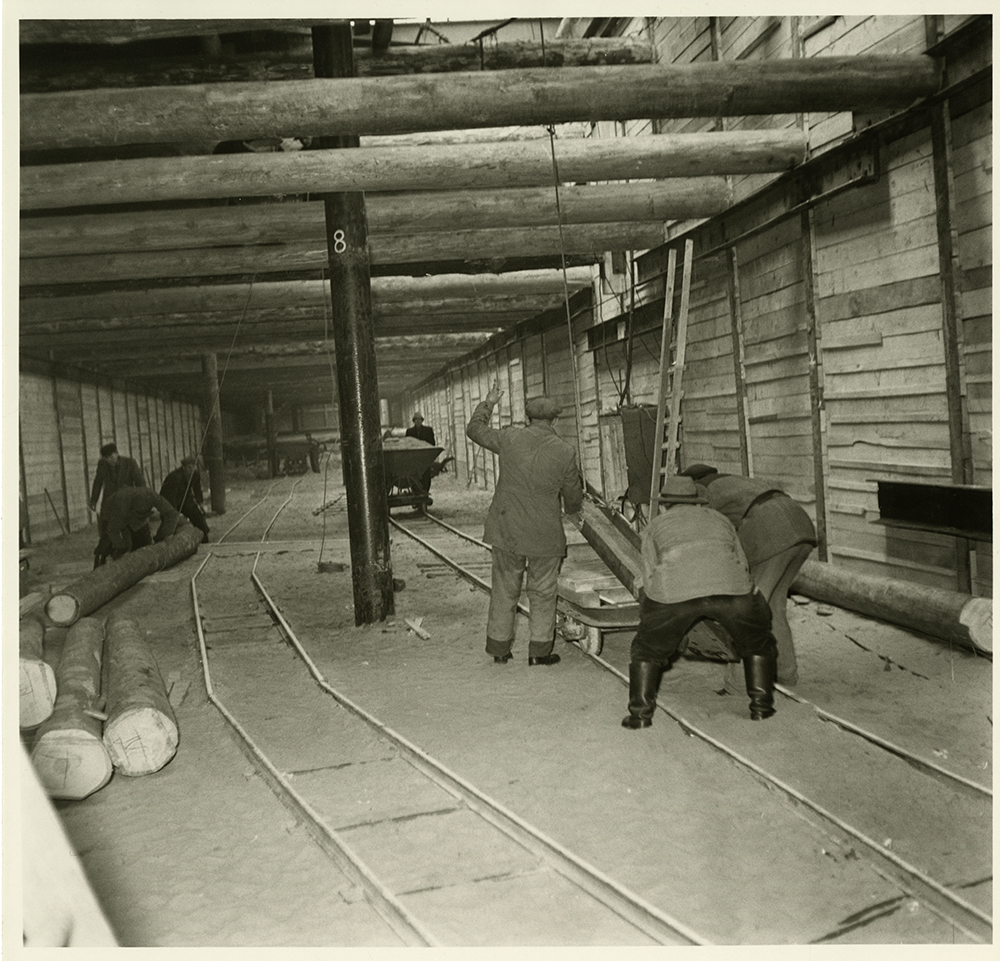

Construction work for the new underground line Seestraße – Tegel (U 6), Picture Agency Schirner, 1954. Inv.-Nr. Schirn 45072/10 © DHM

Of course, construction technology has changed over the past decades. The main line was only 11.2 km long, cost 25 million Reichsmarks, and was opened in two stages. It was followed by further lines that were developed – until Greater Berlin was established in 1920 – by the independent cities and communities of Schöneberg, Wilmersdorf and, as already noted, Charlottenburg. The “inner-city line” (now U2), which opened in 1908, made the old city centre more accessible. It wound its way below ground through difficult terrain, due to the river Spree and the Fischerinsel, from Potsdamer Bahnhof at Leipziger Platz to Spittelmarkt, until it was extended in 1913 to connect with Alexanderplatz. The current numbering of the U-Bahn lines was introduced in 1966. Until the end of the 1920s, the lines were designated by letters. The route between Alexanderplatz and Friedrichsfelde, which opened in 1930, was known as the E line, now U5.

Keep away from the Emperor’s front door!

One central road axis remained a “blank spot” on the Berlin public railway map: Unter den Linden. Only buses were allowed to ride there, including the number 1 bus line, according to old timetables. From 1894, the only North-South connection that crossed Unter den Linden was a horse-pulled tram. It led from the street Hinter der katholischen Kirche – i.e., east of St. Hedwig Cathedral and the opera house – to the “Chestnut Grove” at the Neue Wache. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to allow tramways with overhead electrical lines to be installed there, which he considered unsuitable for the representative character of the grand boulevard. Nothing should block the view between the City Palace and the historical buildings on Unter den Linden, including the Zeughaus, the opera and the cathedral. Wilhelm II was no less irritated that the western façade of the palace was hidden behind a number of older buildings at the so-called “Schlossfreiheit”. They were torn down in 1894 and replaced by the Kaiser Wilhelm National Monument. In future the new Freedom and Unity Monument is to stand there.

View from the Bauakademie to Schlossbrücke und Museumsinsel, righthand side the houses of the Schlossfreiheit. Photographische Gesellschaft Berlin, 1885. Inv.-Nr. Ph 2020717.37 © DHM

It was not until 1916 that the Linden Tunnel was built under the boulevard at this spot. Several electrical tram lines led through it, where it then branched out on the southern side. With a length of 123 metres to one branch end and 187 to the other end, it was fairly short and corresponded approximately to the length of the new U-Bahn station Museumsinsel. When the underground North-South railway (now U6) began operating in 1923, the tram connection became increasingly obsolete. It was partly closed in that year and finally abandoned in 1951.

First rate station architecture

With the (Old) Museum designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and opened in 1825, the Museumsinsel, or Museum Island, was the cultural centre of the city. In 1930, four further museums were added there. It could be reached from Bahnhof Börse (renamed Marx-Engels-Platz in 1951, and then Hackescher Markt in 1992) on the other side of the Spree. With the new Museumsinsel station, Berlin’s art and culture temples are now directly connected with the public transport system for the first time. Around 90 years ago, a “consumer temple” had already assured itself a direct connection to public transport. When it opened in 1929, the department store Karstadt on Hermannplatz had a direct underground entry to the U-Bahn station. Since 1902, its architect, Alfred Grenander, had exerted a huge influence on the buildings of Berlin’s elevated and underground rail system. He was responsible for designing most of the U-Bahn stations, each in its own individual style and colour, including the station at the traffic hub Alexanderplatz, built between 1927 and 1930, where three different lines come together.

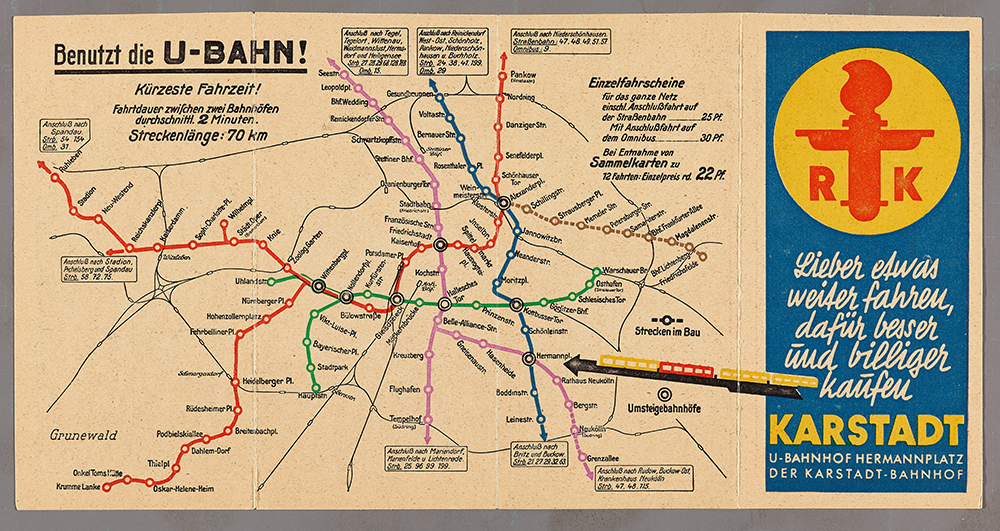

Advertising leaflet for the department store Karstadt at Hermannplatz, with line network map of the Berlin underground, 1930, Inv.-Nr. Do2 2007/669 © DHM

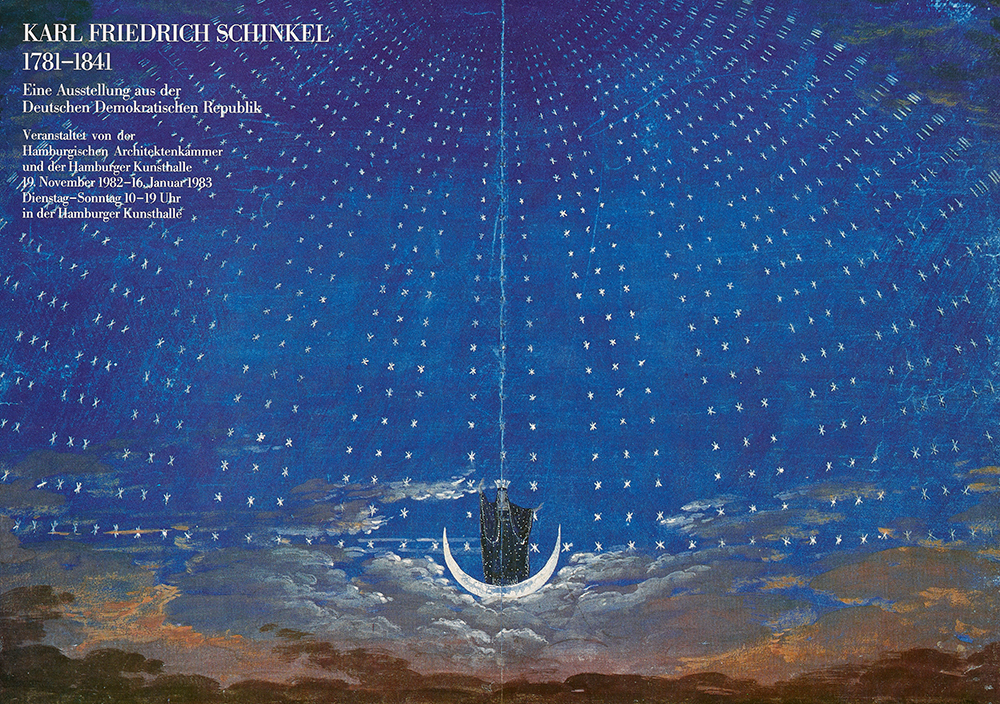

The new Museumsinsel station now presents itself as an understated reminiscence of past Berlin architectural and art history. Its architect, Max Dudler, draws expressly on the history of the location. With their deep-blue colour and 6,662 pinpoints of light, the vaulted ceilings above the tracks recall the starry sky in Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s historic stage decoration for Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute”. Only – in lieu of the Queen of the Night’s famous coloratura aria, we will hear in five-minute tact the no less distinctive warning signal of the closing of the U-Bahn doors.

Poster for an exhibition about Karl Friedrich Schinkel from the inventory of the GDR at Hamburger Kunsthalle, with Schinkels stage design for the opera „The Magic Flute“ as poster motif, 1983. Inv.-Nr. P 98/109 © DHM