What’s that for? One of Richard Wagner’s House Slippers

Franziska Gallusser | 25 May 2022

A silk slipper by Richard Wagner is on loan to the exhibition “Richard Wagner and the Nationalization of Feeling”. Guest author Franziska Gallusser tells us more about the object and how it came to be in Lucerne’s Richard Wagner Museum.

Penchant or Obsession?

In 1866 Richard Wagner moved into what he called his “Tribschen idyll” (named after the spit of land on the outskirts of Lucerne), where he could devote himself entirely both to completing his tetralogy The Ring and to starting a happy family life after having recently fallen in love with Cosima, who would soon be with their second child. However, what is often overlooked in this chapter of his biography is that Wagner also devoted himself wholeheartedly to yet another occupation – namely the furnishing and remodelling of the new domicile. It proved an expensive and time-consuming hobby that was ultimately outstripped by another: the ordering and designing of bespoke clothes cut from fine fabrics. What exactly this sartorial penchant entailed becomes clear from Wagner’s private correspondence with his chosen “finery maker” Bertha Goldwag, which was released to the public in 1877, while the composer was still alive. Wagner ordered silk shirts, jackets, stockings, his iconic velvet berets, nightgowns, but also blankets, cushions, curtains and much more besides from Goldwag, who was his finery-supplier for the best part of a decade, from the early 1860s until 1868. She also made bespoke slippers for Wagner, which she probably produced with generous lining of fur and cotton wool, as the composer often complained of having cold feet. And we have those cold feet to thank for the slipper before us in the exhibition today – which, as an exhibit, is all the more interesting because it was most likely fashioned to Wagner’s precise instructions as per choice of fabric and design. There is also a chance, however, that the slipper was the work of his Lucerne housekeeper Verena Stocker-Weidmann, known from letters as “Vreneli”, who also continued to make clothes for him after his time in Tribschen.

Of Ailments and Fetishes

For the past 150 years, scholars have espoused various theories on Wagner’s “obsession” with fine fabrics. Some share the view that Wagner’s extravagant style of dress was an expression of his very particular tastes and that he purposefully donned such fabrics as a status symbol. Others, meanwhile, hold a much more prosaic view: the composer had little choice but to shroud himself in velvet and silk because he had a long-suffering ailment of the skin – shingles – and therefore had an allergic reaction to cotton and, most certainly, wool. However, this historical diagnosis is flawed in many respects, for even though records show that Wagner did indeed suffer from the disease at several points in his life, we know from the composer’s own manuscripts on the state of his health that he was not plagued by the horrible rash all the way through his life. The slipper is therefore a clear example of Wagner adorning himself in such fabrics because he liked them. For even an extended bout of shingles would not have been reason alone to force Wagner to seek remedy in such elaborate and delicately coloured ornament of slipper, made of no lesser fabric than silk. In this, the slipper is just one of many indicators of Wagner’s general fashion taste. His ‘feminine’ choice of footwear could be seen as a sign of a fetish or even transvestism. Wagner probably wore dresses and women’s underwear in secret. There are numerous records of eyewitness accounts stating that his inclination for wearing clothing that others would have found recherché was not limited to the private sphere. Oddly enough, we also know that he would react with smarting sensitivity whenever the matter of his choice of attire was brought up. For example, his beloved Cosima notes in her diary entry of 24 January 1869: “Unfortunately, R.’s passion for silks gave me cause to make a remark that I should rather have refrained from uttering, because it brought on one of his upset spells.” In the early 20th century, a few decades after his death, Wagner’s extravagant taste in clothes and in particular his intimate knowledge of textiles, their manufacture, and needlework was even interpreted by some as a sign of bisexuality.

A Slipper Makes Its Way Home

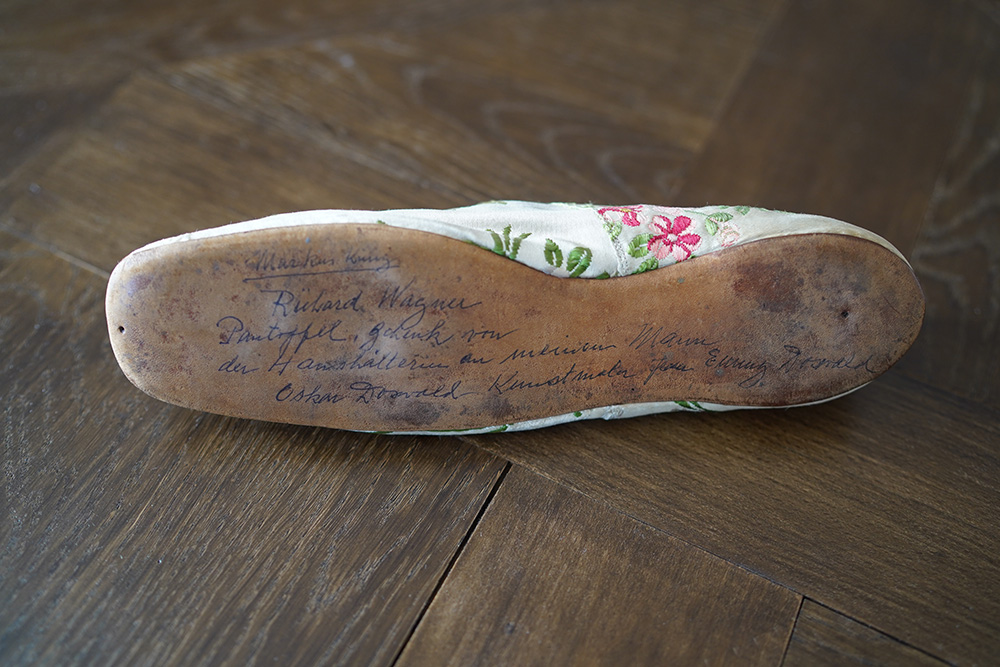

When and how the slipper found its way to Wagner’s foot is unfortunately no longer known to us. But there are more unanswered questions attached to the slipper than just that. For example, one question that instantly arises is: what happened to the other slipper of the pair? The surviving object at least bears an inscription on the sole that connects it with Wagner: “Markus Küng. Richard Wagner’s slipper, gift from the housekeeper to my husband Oskar Doswald – painter. Frau Emmy Doswald.”

When he moved away from Tribschen, Wagner gave the housekeeper he had hired there, “Vreneli”, some personal items as a gift. The slipper was probably one of them. Vreneli presumably subsequently passed on the slipper to Oskar Doswald – and it was his wife who inscribed the sole and in turn passed it on to Markus A. Marljeffsky (born Markus Küng), the son of the painter Walter Küng. The Swiss Richard Wagner-Gesellschaft acquired the slipper and donated it to the Richard Wagner Museum in Lucerne in summer 2009 – where it can be admired – that is when it isn’t away on northerly peregrinations

Further Reading (selection)

Laurence Dreyfus, Wagner and the erotic Impulse, Cambridge etc. 2010.

Ludwig Karpath, Zu den Briefen Richard Wagners an seine Putzmacherin. Unterredungen mit der Putzmacherin Bertha, Berlin 1906.

Paul Simon Kranz, Richard Wagner und «das Weibliche». Zu den Interdependenzen von Philosophie, Leben und frühem Werk (= Frankfurter Wagner-Kontexte 4), Baden-Baden 2021.

Franziska GallusserFranziska Gallusser recently joined the staff at the Richard Wagner Museum in Lucerne in May 2021. She graduated in musicology at the University of Leipzig and at the Sorbonne (Université de Paris IV) and received her doctorate from the Institute of Musicology at the University of Zurich with her dissertation on late Hindemith. From 2019 to 2021 she worked at the Richard-Strauss-Institut near the German-Austrian border. Besides her work at the museum, she is also active at the Tonhalle Zürich, the principal concert hall in German-speaking Switzerland. |