The Eye of Reason

The “artificial eye” of Stephan Zick as leitmotif of the exhibition

Wolfgang Cortjaens | 23 October 2024

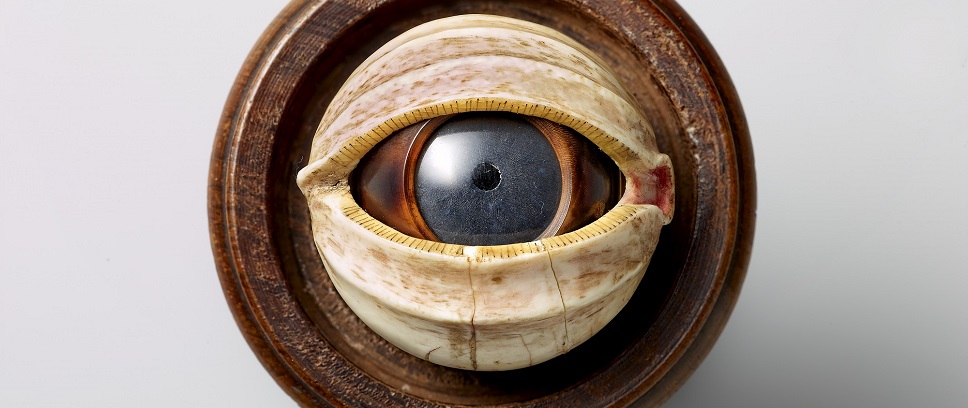

The fixed, reptile-like stare of an artificial glass eye, surrounded by the veined skin of the eyelids and embedded in a ring-shaped wooden holder, is the equally disconcerting and captivating central advertising motif of the current temporary DHM exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”. As such it adorns the catalogue, the poster, and all other promotion materials. But it is only in the exhibition that visitors encounter the respective object in it entirety and can recognise its context.

It is a life-sized anatomical model of a human eye, held in a walnut wood housing perched atop a profiled ivory base, which can be closed by means of a dismountable lid.[1]

The “artificial eye” can be taken out of the housing in which it is resting, unscrewed in three places, and dismantled into eight individual pieces. The eyelid and the half-shell with the finely painted veins are made of ivory, the screw-on receptacle of horn. During assembly in the run-up to the exhibition, the restorer in charge discovered for the first time that the upper shell, which holds the glass lens in place, is made of tortoiseshell, the shell material of the hawksbill turtle, which was also used to make combs and other everyday objects in the past. This material was probably used because of its translucent colour.

Upon closer examination it becomes clear that the surprisingly realistic effects are due to rather simple construction techniques, such as placing painted paper behind the transparent glass “rainbow” (iris). Contrary to other model eyes made in the same workshop whose containers and bases are usually made of precious ivory,[2] the housing of the DHM object consists of turned walnut wood; also unlike comparable examples in which the eyeball can be moved by means of a stick attached to the rear side, the mounting of the displayed object is static. From an anatomical point of view, the eyeball is not correctly designed, but is slightly larger than usual.

No other epoch of intellectual history has devoted itself in comparable variety and intensity to the metaphor of light than the Enlightenment: “… the eye, which could see and examine things, became the privileged sensory organ.”[3] But also the condition of “not being able to see” was increasingly discussed in medicine, science and philosophy, for instance in Diderot’s essay “Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See” (1749), which is located in the exhibition directly next to the “artificial eye”.[4] In the letter Diderot departs from earlier Enlightenment thinkers for whom blindness was a sign of immaturity or underdevelopment; using the example of four blind persons he cites the relief of blindness as a “de-sensualised perception model of sensory perception through blindness as aesthetic staging of aesthetic experience.”[5] Touch for the purpose of sensory experience of the physical world as well as one’s own body became the effective pedagogical method of perception as well as of self-perception. Herder took up this line of thought in his “Physio-Aesthetics”; in the exhibition the tactile stations and the mirror/photo station with the two grimacing “character heads” of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt take reference to Herder’s thoughts on haptics.

The curious “artificial eye” – half anatomical model, half art chamber object – stands for the practice of mutual exchange between science and handicrafts that became so extremely characteristic of the entire Early Modern Age.[6] With the development of the first microscope and telescope at the beginning of the 17th century, the field of optics gradually became established as a scientific discipline of its own. Isaac Newton (1642–1727) made an essential contribution to it; his writings and sketches on optics form an important point of reference in the exhibition, where they are represented by original manuscripts lent from Cambridge University Library. New studies on light refraction and light propagation – Newton’s corpuscular theory of light, according to which light is made up of tiny particles or corpuscles – was later amended by the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) in his Traité de la lumière (1690), the first theory of light waves (the so-called Huyghens–Fresnel Principle), which inevitably raised questions about the processing of visual information in the eye. The anatomy and functioning of the eye were still largely unknown in the 18th century. It was first thanks to the invention of precise optical instruments that ophthalmology (medical eye care) became an independent field of study. The ivory artist Stephan Zick (1639–1759), who came from a Nuremberg dynasty of artistic turners, specialised in eye and ear models made of ivory, precious wood or horn as well as small-scale, full-body models with removable organs and sometimes movable parts.

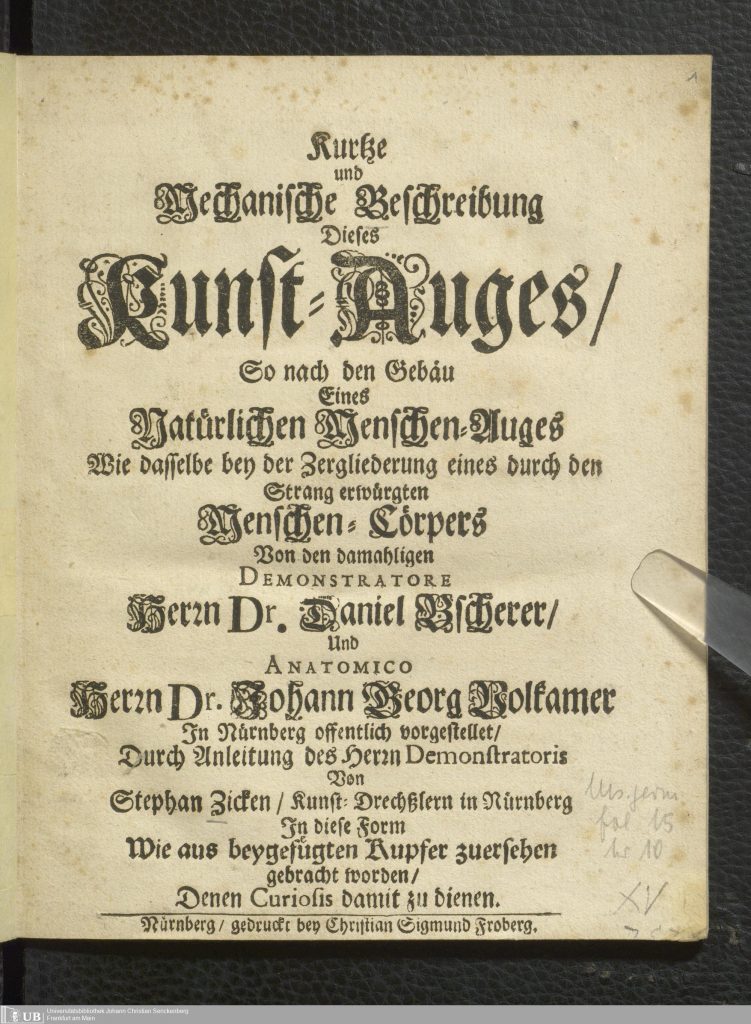

Zick’s model eye was verifiably used in medical practices “for the benefit and teaching of anatomy”. On the cover page of a text accompanying the model eye, Kurtze und mechanische Beschreibung Dieses Kunst-Auges (Short and mechanical description of this artificial eye, ca. 1700), which he probably wrote himself, Zick validated his range of products by referring to the anatomical research of two renowned Nuremberg medical professionals: the physician and botanist Johann Georg Vol(c)kamer the Younger (1662–1744), who had been appointed to the section of anatomical demonstrations of the “Collegium medicum” in 1686, and Nuremberg city doctor Daniel Bscherer (1656–1718).[7] Both owed their knowledge of the structure of the human eye to the public dissection of a hanged man, as mentioned in the longer title of the text.

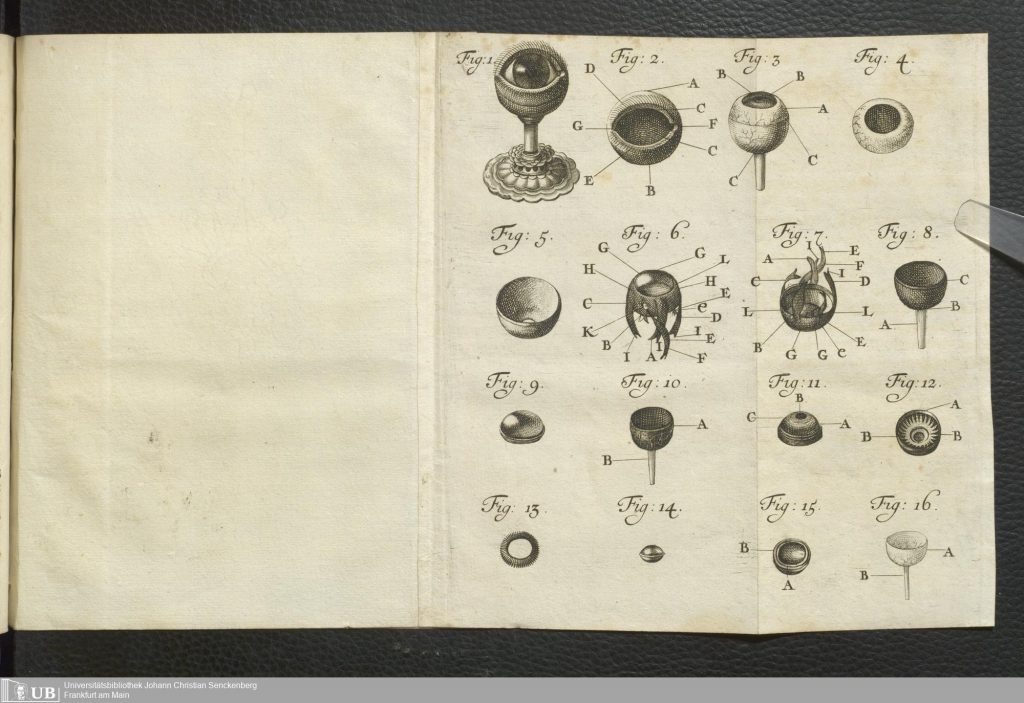

On the basis of the research by Volkamer and Bscherer, Zick’s publication describes the individual components of the human eye and the “artificial eye” and illustrates them with an appended copperplate engraving.

The scientific vocabulary corresponds to a large extent to current German usage, for example the “hornförmige Häutlein” is now called “Hornhaut” (Tunica cornea), but the lens (now “Linse” or “Lens crystallina”) was then known as “Christallinische Feuchtigkeit” (crystalline wetness) and the anterior eye chamber, whose “aqueous humour” serves to moisten the lens and cornea, was called “Gläserne Feuchtigkeit” or “glassy wetness”. Zick’s “artificial eye” brings together several central themes of the exhibition: during this mechanistic age the constantly growing interest in the function and internal structure of the human body, the fascination with optical phenomena including various “sight machines” (among them the perspective theatre and peep-box in the exhibition), as well as the experimental projections and the mirror images.[8] A telling example of this interest is Zick’s identification of the “Netz-Häutlein” (cornea) as the “leading tool of sight” onto which, like a “white sheet spread over a dark chamber (Cameram obscuram)”, the “things of the visible world” are cast and “taken in as in a mirror”.[9] Zick and his colleagues were indeed still a great distance away from comprehending the complex optical processes. This is clearly shown in the concluding statements about the processing of visual information: “… of which the beams thrown in by the crystalline and glassy wetness are brought into different movements / by which manifold movements many things and shapes are seen by the imagination and interpreted by the understanding.”[10] Noteworthy in this connection is the use of the contrasting terms “imagination” and “understanding”. This recalls the increasingly intensive conflict between the positions of empiricism (Locke, Voltaire, Diderot), according to which all knowledge can be deduced from inner or external sensual experience, and those of rationalism (Leibniz, Wolff, Kant), that postulated a knowledge a priori. In the text by the artistic turner from Nuremberg, reason also appears as the decisive instance of judgement, thus allowing an interpretation of the model eye as pars pro toto for the groundbreakingly innovative, scrutinising knowledge of seeing, which contrary to the curiosity cabinets and wonder chambers of the early modern age that were devoted primarily to the amazement of the spectators, helped to found a science based on the desire to penetrate the physiological processes.

Illustrations

Ill. 1, 2, 3, 4: Anatomical model of a human eye in a holder, Stephan Zick (?) (1639–1715), Nuremberg, ca. 1700, walnut wood, horn, carved and turned, glass, paper, Deutsches Historisches Museum: 1991/2641

Ill. 5: Anatomical teaching model of a pregnant woman, Stephan Zick (1639–1715), Nuremberg, ca. 1680/1700, ivory (figure, pillow), wood, leather, satin, trimming (case), Deutsches Historisches Museum: KG 96/27

Ill. 6, 7: Short and mechanical description of this artificial eye …, Nuremberg (ca. 1700), Permalink: urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:2-229185 (accessed 14.10.2024)

[1] Cf. Leonore Koschnick, “Modell des menschlichen Auges mit Behältnis”, in: Bilder und Zeugnisse deutscher Geschichte. Aus den Sammlungen des Deutschen Historischen Museums, Berlin 1995, p. 187; Wolfgang Cortjaens, “Model of a human eye in a cup”, in: Raphael Gross und Liliane Weissberg (eds.): What is Enlightenment? Questions for the Eighteenth Century, Munich 2024, p. 93.

[2] Cf. for example the model eye on a spiral-shaped, turned ivory base in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nuremberg (Inv.-Nr. WI2282), cf. Susanne Thürigen, “Gläserne Augen”, in: Sabine TIedke (ed.): Meisterwerke aus Glas, Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums 2023, Kat. 25, p. 106f.

[3] Liliane Weissberg, “Asking Questions”, in: Gross/Weissberg 2024 (as in Fn. 1), p. 13–26, here: p. 16. On the light metaphor see in particular the articles there by Horst Bredekamp and Daniel Fulda.

[4] Denis Diderot: Lettres sur les Aveugles: A l’Usage de Ceux Qui Voyent, London 1749, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Sign. Nf 9532.

[5] Cf. Kai Nonnenmacher, Das schwarze Licht der Moderne. Zur Ästhetikgeschichte der Blindheit, Tübingen 2006, p. 5; on Diderot esp. pp. 47–92.

[6] Cf. Frank Matthias Kammel and Johannes Pommeranz: “Das Modell als Kunstwerk”, in: Frank Matthias (ed.): Leibniz und die Leichtigkeit des Denkens. Historische Modelle: Kunstwerke Medien Visionen, Nuremberg 2016, p. 134. In 1727 the Nuremberg merchant Johann Magnus Volkamer (1671–1752), a grandson of the botanist and owner of a “small art chamber”, still numbered among the “admirable things” in his collection several “artfully turned ivory pieces by old Zick and his son”. Cf. Neickel, Museographia oder Anleitung zum rechten Begriff und nützlicher Anlegung der Museorum, oder Raritäten-Kammern, Leipzig 1727, p. 167.

[7] Cf. Kurtze und mechanische Beschreibung Dieses Kunst-Auges, So nach den Gebäu Eines Natürlichen Menschen-Auges Wie dasselbe bey der Zergliederung eines durch den Strang erwürgten Menschen-Cörpers Von den damahligen Demonstratore Herrn Dr. Daniel Bscherer/ Und Anatomico Herrn Dr. Johann Georg Volkamer/ In Nürnberg offentlich vorgestellet/ Durch Anleitung des Herrn Demonstratoris Von Stephan Zicken/ Kunst-Drechßlern in Nürnberg In diese Form Wie aus beygefügten Kupfer zuersehen gebracht worden ; Denen Curiosis damit zu dienen, Nuremberg, printed by Christian Sigmund Froberg, the Younger [ca. 1700]. Digitalisied by the University Library J.C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main [2015]: Permalink: urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:2-229185 (accessed on 14.10.2024).

[8] Cf. Ulrike Boskamp, “Nachbilder, nicht komplementär. Augenexperimente, Sehlüste und Modelle des Farbensehens im 18. Jahrhundert”, in: Werner Busch und Carolin Meister (ed.): Nachbilder. Das Gedächtnis des Auges in der Kunst, Zürich 2011, pp. 49–70.

[9] As in footnote 4, p. 20.

[10] Ibid.