“Roads not Taken” on 9 November 1918

6 November 2024

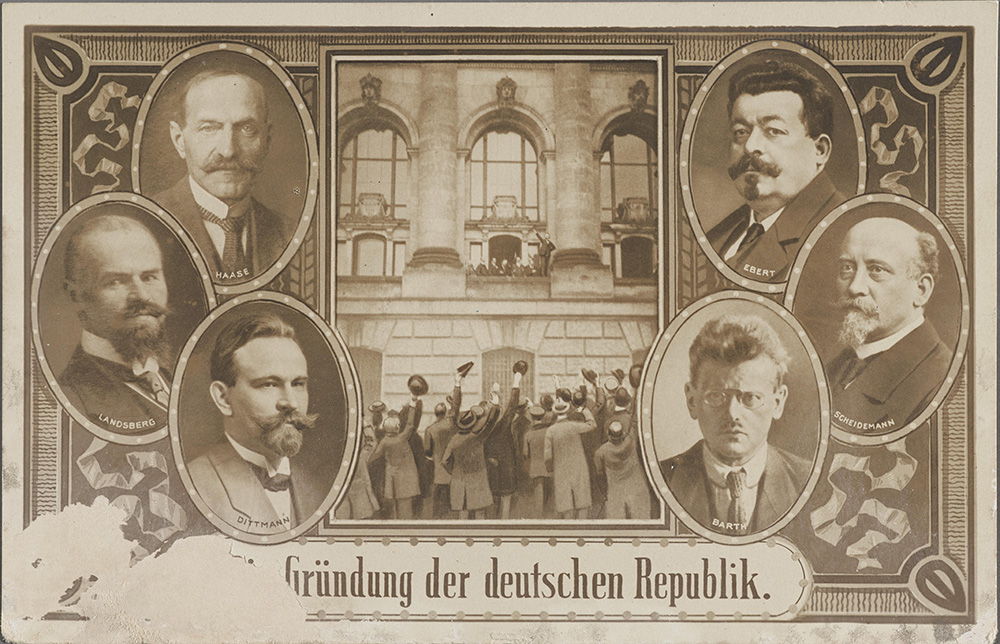

The word “republic” resounds from mouth to mouth – this was the headline of the 8 pm evening newspaper on 9 November 1918. Many speeches were held from the Reichstag Building on this day.[1] One of the most famous ones was that of Philipp Scheidemann, who until the morning of that famous day was still a state secretary in the parliamentary-backed imperial government. There are different versions of the exact text of his “proclamation”. The authenticity of the only known and preserved photograph that shows the “historic moment”, as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, published by Verlag Ullstein, wrote, has also frequently been doubted. In fact the “knowledge” that this iconic photo had been manipulated has apparently become part of the collective memory of the date 9 November 1918.

The Revolution of 1918 is one of the 14 turning points in German history taken up in the DHM exhibition “Roads not Taken”. On the occasion of the second anniversary of the opening of the exhibition, which runs until 11 January 2025, Dr Lili Reyels, curator of the exhibition, spoke with Dr Katrin Bomhoff of the ullstein bild collection about the authenticity of the photograph, the way it came about, and the process of its publication.

Lili Reyels: Dr Bomhoff, what can be said about the original photograph that is preserved in your collection?

Katrin Bomhoff: It is a very small photograph, measuring 3.8 x 5.5 cm, printed on approximately postcard-size photo paper. We do not know whether the negative, which is not extant as far as we know, was printed at Ullstein as a contact print in the present standard postcard size. The reverse side contains a contemporary picture caption: “The first proclamation of the new republic by Philipp Scheidemann from the balcony of the Reichstag Building.” The photographer, Erich Greiser, Berlin/Lichtenberg, is also named and there are several inventory and archive numbers. On the lower right is the number 47/1918, representing the date of its first publication; the newspaper itself is not named – at Ullstein it was clear that this meant that it was published in the highest-circulation newspaper, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ), on 24 November 1918.[2]

LR: How can we imagine the publication process of the picture at the time?

KB: The scene in the photo was enlarged in the newspaper, then measuring 11.2 x 15.5 cm, and cut off on all sides so that the detail itself was enlarged. In the newspaper there is also conspicuous luminous highlighting that brings out the silhouette of the speaker on the balustrade vis-à-vis the columns. It is one of the reasons why the photo was thought to be a montage. That it is probably Scheidemann in the picture is only revealed in the caption. It can be assumed that the photographer Erich Greiser brought the photograph directly to the editorial office – this gave the publisher something the competition did not have: an illustration of the “historic moment”. “We are in a position to show the rare photograph to our readers today,” wrote the BIZ on 24 November 1918. The intertwining of image and text strengthened the legitimation of the “German Republic” – Scheidemann’s proclamation occurred only two hours before the proclamation of the “Räterepublik” (Soviet Republic) by Karl Liebknecht, of which no photograph exists, however. Thus, not only Erich Greiser, but the publisher Ullstein made photographic history.

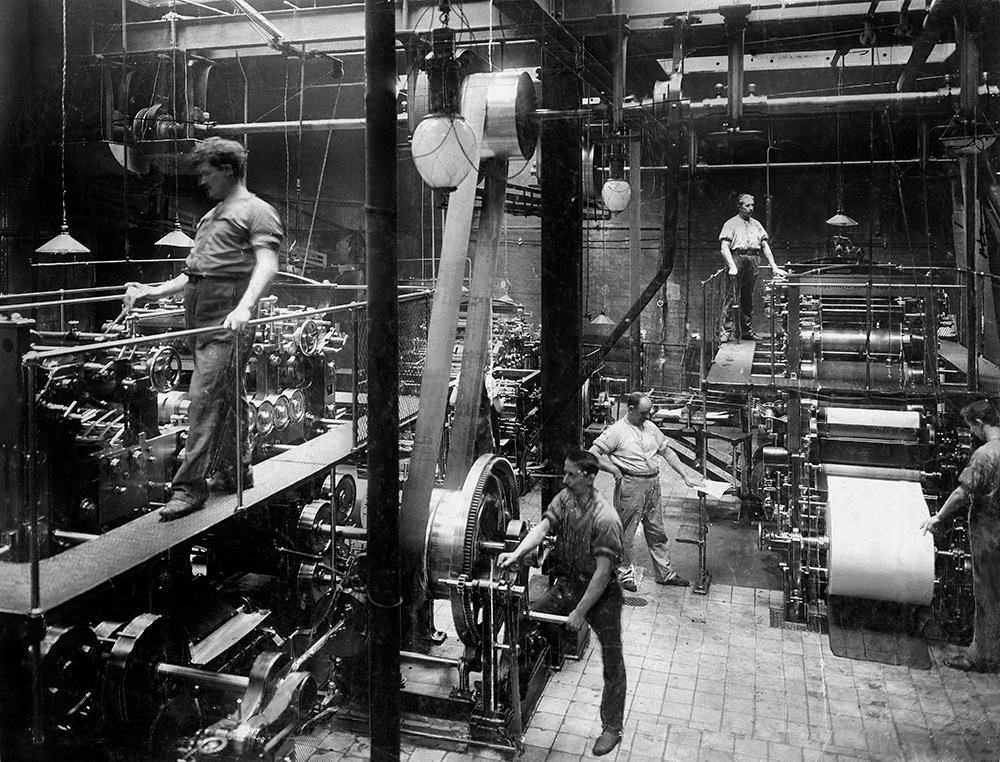

LR: How did the printing process function technically at Ullstein?

KB: The newspaper was printed on a rotary press. The first rotary machine, which could print pictures and text simultaneously, was used from 1902 on to publish the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. This functioned according to the printing principle “round on round”. The photo was reproduced using an autotype or halftone process. By printing on cylinders that are constantly turning in one direction it is possible to work more quickly than with a sheetfed press, thus achieving a higher circulation. Karl Korff, later editor-in-chief of the newspaper, described the development: “When the World War broke out, the ‘Illustrirte’ had grown to a circulation of almost one million copies, during the trench warfare it was rounded down from the million circulation number, then sank during the time of inflation to 450,000, and finally rose again, reaching 1.75 million by the end of 1926 and thus a peak that had never before been achieved in the German newspaper business.”[3]

LR: How did the collaboration between editors and photographers function?

KB: The Verlag Ullstein worked very deliberately and successfully on its strategy of retaining good press photographers. In the 1920s more and more exclusive contracts were concluded, whereby large photo agencies had already been established by the turn of the century. Street photography took the place of studio photography. In a programmatic article “The Photographer as Journalist”, the BIZ wrote on 14 December 1919: “The photographer wanders around the world for you and brings it near to you. He (stands) amidst the exchange of fire between Spartakus and the government troops. And he does all this so that you can be everywhere where you could not be otherwise (…).”[4] It was a decisive time for the press agencies and for press photography, and it was at this time that the Ullstein photo archive was formed. The fact that amateur photographers like Erich Greiser could get a chance to publish a photo of such an important event is unusual. We know of some amateur photos of the revolution, and the number of amateur photographers had grown considerably during the World War. At this time there were many pictures of the different speakers,[5] but professional press photographers were usually on hand when Liebknecht, Ebert or Scheidemann spoke in public. Greiser’s photograph is singular.

LR: What do you think of the assumption that the photo is a montage?

KB: Statements about the authenticity of the picture can be based among other things on the location of the photographer when he “snapped” the photo. As the photography historian Dr Ludger Derenthal from the Museum for Photography in Berlin assumes[6] and has explained in an interview[7] with the ullstein bild collection, Greiser probably stood with a folding roll film camera on the back parapet of the broad access ramp to the portal of the Reichstag. Today the ramp is no longer accessible. According to Derenthal, an indication that it is not a montage is the fact that a bit of the front parapet of the ramp shines through the crowd of cheering spectators in the picture. It is also unlikely that it is a montage because the photograph itself is technically too poor for that. There are compelling photo montages from that time, especially with lead pictures of the newspaper. Possible retouching could occur where cannon smoke is added, for example, or other scenes are manipulated to illustrate the fighting. On the other hand, Greiser’s photo is relatively blurry compared with professional photographs and somewhat underexposed. Furthermore: What would have had to take place in the editorial office or with the photographer in order to falsify the photo? The picture would have had to be rephotographed and the rephotographed photo would then have to be manipulated. If it had been retouched, we probably could see it directly on the photo print.

LR: Why do you think the photo has iconic quality?

KB: On the one hand, precisely because of the charm of the picture, that it is more or less a snapshot that captures an important moment. The photo was published very soon after Scheidemann’s appearance at the Reichstag. But above all, there is the symbolic charge emanating from the situation, not from the speaker. The picture was widely disseminated on postcards and reproductions, which were very popular at the time. The comparison with later postcards shows that the photo found in the Ullstein photo archive is as close as it can get to the original lost negative.

LR: How can we imaging your work with such a famous photo in the archive? What requests are received at ullstein bild?

KB: The photo is regularly requested by schoolbook publishers, newspaper companies and TV broadcasters, for example. Very often we are confronted with the assumption that the picture is a montage or a forgery. And we are pleased to lend this original photograph for exhibitions, like other unique photos from the Ullstein Collection at ullstein bild.[8]

[1] Cf. Mühlhausen, Walter: Die Ausrufung der Republik am 9. November 1918 durch Philipp Scheidemann, p. 31, Erfurt 2022

[2] Ullstein Verlag & Co, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung from 24 November 1918, No. 47, p. 372

[3] Kurt Korff, Die ’Berliner Illustrirte’, in: 50 Jahre Ullstein – 1877-1927, Berlin 1927, p. 301

[4] Bomhoff, Katrin: Berliner Revolutionsfotografien in der Sammlung Ullstein Bild, in: Derenthal, Ludger, Förster, Evelyn, Kaufhold, Enno: Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919. Fotografie, Film, Unterhaltungskultur, p. 95, Dortmund 2018

[5] Cf. https://www.axelspringer-syndication.de/artikel/berlin-der-revolution

[6] Derenthal, Ludger: “Ein historischer Augenblick”. Philipp Scheidemann am 9.11.1918 auf dem Balkon des Reichstagsgebäudes, fotografiert von Erich Greiser (unpublished manuscript of a lecture at a conference in the Museum for Photography, Berlin, 1 March 2019, kindly made available by the author.)

[7] https://www.axelspringer-syndication.de/artikel/ausrufung-der-republik-1918

[8] https://www.axelspringer-syndication.de/angebot/ausstellungen