What´s that for? A premium medal for parents willing to have their children vaccinated

Saro Gorgis | 27 November 2024

In the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century” there is a premium medal from the DHM collection that celebrates the medicinal progress in smallpox immunisation and is awarded to parents who allowed their children to be vaccinated. Saro Gorgis, research associate for the exhibition, explains what vaccination has to do with the Enlightenment and why medals were issued to accompany the state’s campaigns for vaccination.

The 18th century is sometimes called the century of smallpox. Even more than the plague, cholera or wars, it was smallpox – also known as variola for the virus that causes it – which was responsible for a stark decimation of the population between the 16th and 18th centuries. The death rate lay on average between 10-20%,[i] whereby children were most seriously affected. The virus raged disastrously on the American continent as well. Brought there by Europeans, it was used as a biological weapon of war against First Nations in the 18th century to break their resistance to colonisation.[ii]

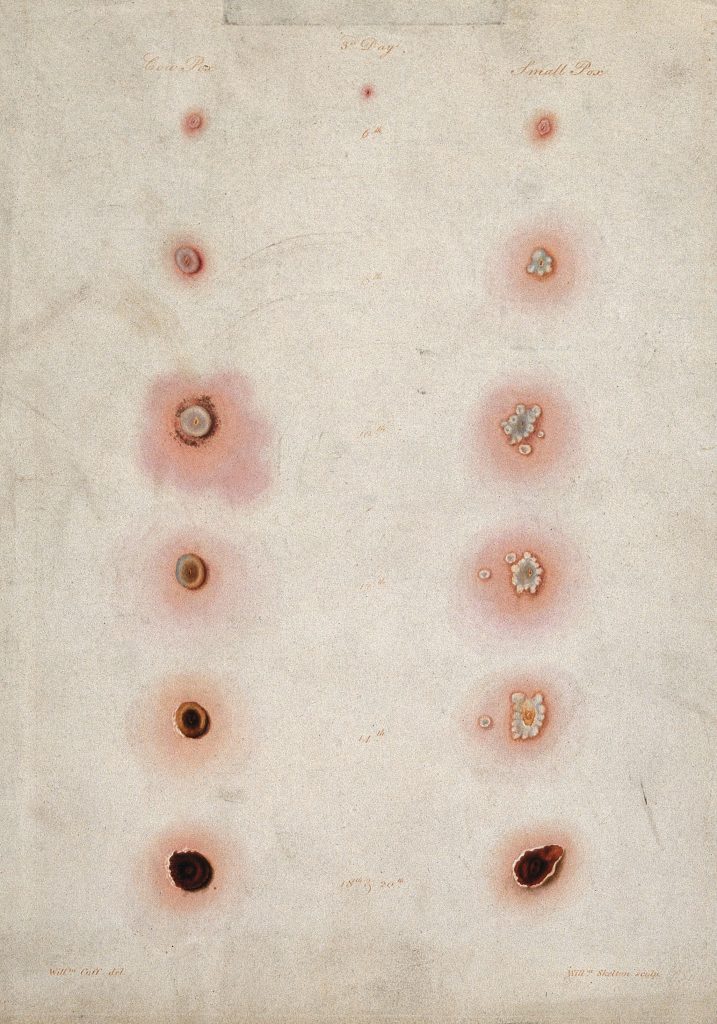

One of the earliest methods of protection against smallpox was a procedure known as variolation, which came from Asia to Europe at the beginning of the 18th century and was first widely used in England: A small amount of pocks from a person with a mild case of smallpox was inserted into a small cut in a child’s flesh in order to create a controlled infection and thus immunise them. The English country doctor Edward Jenner (1749–1823) set a further medical milestone with a far less risky method of vaccination (the name comes from the Latin vacca – cow). In 1796 Jenner had observed that the pus of the considerably milder cowpox also triggered an immunisation against the life-threatening human smallpox. The cowpox lymph was either inoculated directly from arm to arm or placed in a glass tube and sent to a physician or medical layperson for further use. There it was extracted by means of a so-called vaccination thread soaked in the lymph. The secretion was then applied to a small cut in the flesh made with a lancet.[iii]

While the variolation method had already washed a wave of Enlightenment writings onto the market – Voltaire and Kant were among those who participated in the debates –, around 1800 even more flyers, newspaper and magazine articles, brochures and books promoted the new inoculation procedure for vaccination. Alongside agricultural topics, popular medicinal education had become the principal object of rural edification.[iv] Only a few scholars thought that developments were going too quickly, among them the Jewish Enlightenment advocate, physician and philosopher Marcus Herz (1747–1803), who warned against an “overhasty grafting of animal manure”.[v] Although other Jewish scholars and rabbis welcomed the new method, for Herz the vaccination also represented a metaphysical problem of crossing the physical boundary between animal and human life. Edward Jenner’s accidental, empirical discovery also contradicted Herz’s rational understanding of science and medicine: the causes of illnesses should be identified and cured with the help of logical analogies, he believed.[vi]

Borne by an unimpeded faith in progress and the conviction that one is responsible for one’s own fate, many other Enlightenment thinkers hoped, on the other hand, for a speedy eradication of the dreaded disease – and for a change in the mindset of the population.

But the general public could not be convinced by printed works alone. Neither medical arguments and statistics nor theological-moral and emotionalised appeals to the parents brought about a major change. Uneven alphabetisation, high vaccination costs, legitimate fears of side effects and infectious diseases, but also traditional attitudes and notions – often dismissed by Enlightenment thinkers as “prejudice” or “superstition” – hampered the acceptance of vaccinations. Smallpox was seen by the rural population as a necessary and natural phenomenon of human development, a process of maturing and cleansing that was needed for the reproduction of the bodily fluids known as the four humours, or seen as natural birth control, but also as God’s punishment or a test of one’s faith.[vii] Similar to when the lightning rod was introduced towards the middle of the century, people were afraid that by accepting this medical achievement they would invite the wrath of God by deliberately defying His Providence.

To increase people’s willingness to be vaccinated, it was therefore necessary to resort to more subtle methods and inducements. Clergymen swayed a large circle of people through enlightened preaching. Public instructional readings and public vaccinations were carried out at the marketplace, the central venue for the communication of popular enlightenment. The Duchy of Braunschweig financed vaccinations free of charge,[viii] as did the “Königlich-Preussische-Schutzblatter-Impfinstitut”, founded in Berlin in 1802. Every Sunday from noon until 2 o’clock in the afternoon, this Royal Prussian smallpox vaccination institute welcomed citizens who were willing to be vaccinated.

The elite classes of society, particularly the aristocrats and members of the royal houses, who were already active in mid-century as promoters and opinion makers, also played an important role in popularising vaccination. For example, after overcoming the disease, Empress Maria Theresia (1717–1818) effectively promoted the cause by having her own children publicly vaccinated and by establishing an inoculation house in Vienna for the population. After her wondrous recovery the imperial medallist Anton Franz Widemann minted a celebratory medal in 1767, inscribed DEO CONSERVATORI AUGUSTAE [God, Saviour of the Empress] and dated OB REDDITAM PATRIAE / MATREM 22 IVLII / MDCCLXVII [On the occasion of the recovered Mother of the Fatherland, 22 July 1767]. The front side shows a bust with a right-side profile of Maria Theresia, while a kneeling religious figure on the reverse swings an incense burner before an altar.[ix]

In the Early Modern Age medals were popular collector’s items and objects of value. They could be used to spread visual and verbal messages internationally. It is therefore no wonder that medallions were minted in connection with anti-smallpox prophylaxis and distributed as a material vaccination incentive.[x] A medal with a bust of the “discoverer of preventive vaccination”, Edward Jenner, was minted by the Loos family in their Berlin mint.[xi] On the reverse, children dance around a cow that is being adorned with floral wreathes by a genius in the clouds. The figure is circumscribed by the words EHRE SEY GOTT IN DER HÖHE / UND FREUDE / AUF ERDEN [Glory to God and Joy on Earth]. The medal was destined for parents who willingly had their children vaccinated.[xii]

Individual states gradually introduced mandatory vaccination against smallpox. In 1807 the Kingdom of Bavaria was the first state to require immunisation. In Prussia compulsory vaccination was first enacted in the Reich Vaccination Law of 1874.[xiii] Russia, Spain and Portugal did not have laws requiring immunisation.[xiv] Without such a legal obligation, government authorities and popular educators had to depend on reasoning and creative strategies to promote vaccination acceptance. Many years were to pass before the WHO declared the world free of smallpox, in 1979. Until this day, smallpox is the only infectious disease to be eradicated from the global map by systematic scientific efforts.

[i] Cf. Marcus Sonntag, Pockenimpfung und Aufklärung. Die Popularisierung der Inokulation und Vakzination. Impfkampagne im 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhundert, Bremen 2014, p. 14.

[ii] Cf. Andrew M. Wehrman, The Contagion of Liberty. The Politics of Smallpox in the American Revolution, Baltimore, Maryland 2022, p. 33.

[iii] Cf. Roland Schewe und Barbara Leven, “Scharf, spitz und durchsichtig. Seltene Impfutensilien, ihre Geschichte(n) und ein unerwartetes Paradoxon”, in: KulturGut. Aus der Forschung des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, III. Quartal, H. 70. (2021), p. 10, DOI: https://doi.org/10.11588/kg.2021.70.82667

[iv] Cf. Holger Böning, Medizinische Volksaufklärung und Öffentlichkeit, in: Internationales Archiv für Sozialgeschichte der deutschen Literatur, Bd. 15, H. 1 (1990), p. 7.

[v] D. Marcus Herz an den D. Dohmeyer, Leibarzt des Prinzen August von England über die Brutalimpfung und deren Vergleichung mit der humanen. Zweiter, verbesserter Abdruck, Berlin 1801, p. 12.

[vi] Herz 1801, p. 32; Cf. David B. Ruderman, “Some Jewish Responses to Smallpox Prevention in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century: A New Perspective on the Modernization of European Jewry”, in: Aleph, Nr. 2 (2002), p. 140.

[vii] Cf. Sonntag 2014, p. 50.

[viii] Cf. Sonntag 2014, p. 137.

[ix] Cf. Eduard Holzmaier: Katalog der Sammlung Dr. Josef Brettauer, Medicina in Nummis, Wien 1937, Cf. Nr. 1571.

[x] Cf. Marien C. Biederbick, “Medaillen als Mittel der Impfpopularisierung”, in: VIRUS – Beiträge zur Sozialgeschichte der Medizin, Nr. 20 (2021).

[xi] Cf. Klaus Sommer, Die Medaillen des königlich Preußischen Hof-Medailleurs Daniel Friedrich Loos und seines Ateliers, Osnabrück 1981, A 104.

[xii] Cf. Ibid. Sommer 1981, A 104; Münch 1994, p. 74.

[xiii] Cf. Wolfram Kerscher, Der preußische Weg zum Impfzwang. Die Entwicklung der preußischen Pockenschutzimpfung 1750–1874, Bonn, 2011, p. 65.

[xiv] Cf. Ibid. 72.

|

|

Saro GorgisSaro Gorgis is a research assistant for the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th century” at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |