Collecting, Preserving, Researching: A look behind the scenes of the collection work of the Deutsches Historisches Museum

Fritz Backhaus | 18 December 2024

The following article is an introduction to a new series on the collection work of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM), describing and expanding on various aspects of this activity. It deals with core questions such as the decision for or against the acquisition of certain objects, the different ways in which they are found and acquired, the changing research questions posed by the objects in the collection, the ways the provenance and origin of the objects can be traced, and many other aspects.

Fritz Backhaus, director of the DHM department of collections since December 2017, deals with the complex reasons for deciding to take an object into the DHM collections and throws light on the various aspects that lead to such decisions as well as the fundamental premises involved in acquiring objects for a history museum in Germany and the consequences this has for a museum’s collections.

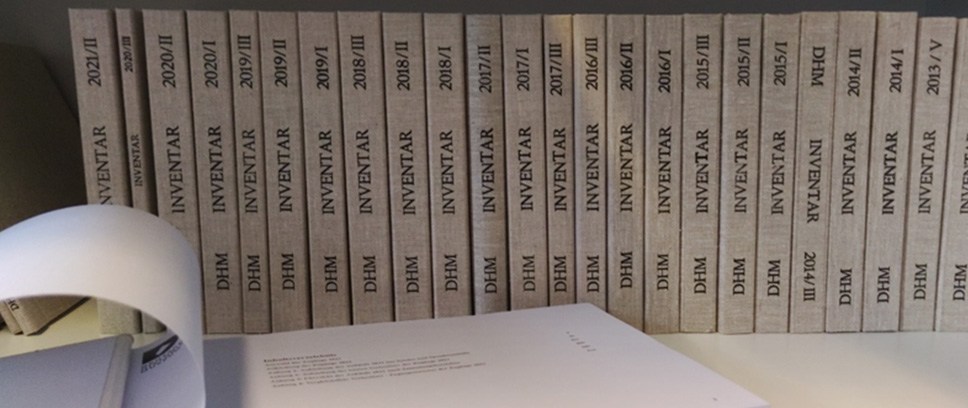

In June 2024, it was again my responsibility to sign the inventory book for the year 2023. Under the further signatures of the head of Central Documentation, Dr Brigitte Reineke, and the relevant staff member Nina Bätzing, the book documented the acquisition of 5,673 objects: a three-volume, solidly bound official document that records the annual growth of the museum’s possessions in a legally binding manner. Every year it is a special act, because it connects the work of the museum with the promise to create something for “posterity” and to carry on the series in our collection that began with the inventory book of the year 1883.

If we add all of the eight inventory books together that I have signed, they record the acquisition of more than 50,000 objects. Less than half of them were purchases from auctions and private clients, and up to two-thirds of a yearly acquisition were from donations. This high share shows the trust the DHM enjoys, because many of those bestowals have to do with the past and the personal memories of the donors or their families and are connected for them with positive or negative emotions.

Altogether some 786,000 collection objects are listed in our database. In addition there are probably around two- to three-hundred-thousand objects in the collection that stem above all from the time of the former East German Museum für Deutsche Geschichte (MfDG) and have not yet been transferred to the digital list. When you first hear these numbers and realise the annual growth, you might think of Grimm’s fairy tale of the “Magic Porridge Pot”. When a magic spell is spoken, everyone is happy that the porridge grows and grows, but when they forget the spell on how to halt the growth, it no longer stops and ends up covering the entire city. Collecting in the museum therefore also means that we have to think about the “limits of growth”. On the other hand, every new acquisition triggers our curiosity and enriches our knowledge of the past. Or else it is a testimony from our time that will later expand the knowledge of future generations about our world.

Behind the new annual additions there are therefore decisions that have to be prepared and made by the heads of the different collections. The colleagues sift through dozens of auction catalogues and hundreds of sales or donation offers, and then make their appraisals and recommendations for objects that might be acquired. This can also go hand in hand with intensive personal discussions with those who offer the objects, because with historical objects it is crucial to document their context, which defines their historical importance. But – and this can meet with incomprehension – after careful consideration we sometimes have to turn down donation offers.

But what are these decisions based on? In the foundation’s statues of 2010, it is stipulated that the DHM should present the “entire German history in its European context” and that “the acquisition of realia on German history as well as their inventorying, documentation and, if necessary, their restoration” shall serve among other things the “fulfilment of this aim”. On closer examination, this seemingly clear objective raises a great many questions: When does German history begin? With the Teutons and Romans, the Franks and Charlemagne, or with the Humanists of the 16th century who first sought to describe and define what something like Germany could consist of? Why only the “European context”? What about Germany’s colonial history, the emigrants to America, the textile factories opened by Germans in Bangladesh, the global effects of the fossil fuels burnt in Germany, the role of Germany in the Near East conflict? And as to German history: What topics does the adjective “entire” comprise – political, social, technical, artistic, economic …? And finally: What are, after all, the realia that we should be collecting, preserving and researching?

The original concept was developed above all to differentiate real and visual testimonies of the past from historical archive material and written records – the main sources of historiography, which are preserved primarily in archives. Realia, on the other hand, are held – if they do not end up in private collections – above all in museums, which developed out of the art and curiosity collections of the Early Modern Age and the bourgeois clubs and associations that were founded in the 19th century. The seemingly old-fashioned term “realia” is connected with the opening up of historiography to the findings of the sciences that have to do with things, such as archaeology, the cultural and visual sciences, European ethnology, or many of the natural sciences.

The variety of what realia can be is reflected in the structure of our collection: manual and technical devices, advertising panels, toys, clothing, flags, paintings, sculptures, posters, graphics, photos, furniture, cutlery, books, rare prints, documents, coins, medals, securities, weapons, uniforms – a list that could go on and on. It is remarkable that there is actually no specific group of objects that are found only in the DHM – our collections coincide with those of art and arts-and-crafts museums, museums of European ethnology, archaeological museums as well as museums for communications, photography, posters or military objects. And there is (almost) no object group that is not represented in our museum, and that is its strength and singularity. The aim is not comprehensiveness, but rather diversity.

Today the museum houses a copious and multifaceted collection which in its broad diversity reflects German history and provides a source for an unlimited number of historical questions. It is remarkable that the DHM’s basic concepts from the 1980s were clear from the very beginning, namely that the museum would compile a collection, but would remain open to discussion about what, exactly, was to be collected; in other words, it was decided to refrain from formulating an explicit collection conception. The extensive concept for the planned Permanent Exhibition served as orientation for the acquisitions that were to be made. It comprised more than one hundred different topics and a time frame from the early Middle Ages to the 20th century.[1] The focus of the collecting activity – as remembered by the original collection staff – was above all the planned thematic rooms on social history, but the core of the concept was the aim to create a material base for the Permanent Exhibition. Everyone was also conscious of the fact that despite an opulent initial acquisition budget, it would take decades to build up a significant collection.

Three years after the founding of the museum, the fall of the Berlin Wall made the planning obsolete. The last government of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) transferred the title and contents of the Zeughaus and the collection of the East German MfDG, founded in 1952, to the planned Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) in West Berlin: half a million “Sachzeugnisse” (the term of the MfDG for realia), ranging from primitive society and feudalism to the socialist society of the GDR.[2] It also included the collection of weapons, uniforms, military badges and visual images that had come down from the army museum, which had been dissolved in 1945. It had been opened in 1883 as the Prussian military museum for the glory of the Hohenzollern dynasty. The MfDG had taken over the stocks of the Zeughaus containing the weapons arsenal of the Prussian military that had been collected since the beginning of the 18th century. The aim of the collection of the MfDG was to provide evidence that would represent a Marxist-Leninist concept of history, but it is obvious that the staff brought together a spectrum of historical exponents that went far beyond these ideological guidelines. Our present collection therefore represents many different concepts of history: from the founding of the Hall of Honour of the Hohenzollern, to the National Socialist army museum, the socialist museum of German history, and finally to the present-day DHM with its liberal-democratic basis and an open concept of history.

It would, however, come far too short to see the objects in our collection only as testimonies to various historical conceptions. Objects have their own tenacity. The hat of Napoleon, for example, once carried off in the Battle of Waterloo and preserved as testimony to the Prussian triumph, now stands for the development of the Napoleon “brand” due to its plain bicorn, an indispensable detail found in every caricature; it also stands for the modernisation of Germany under Napoleon, for the hundreds of thousands of casualties in a twenty-year-long war, for the hat fashion around 1800 – the list is by no means complete. Or let’s take the instant glue that was used in a protest action by the “Last Generation” and was recently taken into the collection. In a hundred years it might no longer be of interest as evidence of a political action, but instead as an example of a primitive glue. These examples show an essential characteristic of the objects in our museum: They don’t necessarily tell us a story – the often used colloquial formulation –, but they convey meaning, they are semiophores, as Krzysztof Pomian put it[3] – meanings that we ascribe to things and that are the basis for the decision to preserve them. The meanings that we ascribe to the objects in a museum, however, are not arbitrary. They have to be based on facts, i.e., on historical sources, and be determined on the basis of methods appropriate to the historical sciences. And therefore they also have to stand up to the critical judgement of science and the public.

Another thing that applies to museum objects: The meaning that is ascribed to an object when it is taken into the collection, together with the inventorisation, preservation, restoration and study involved, withdraws the object permanently from the economic process of the utility of things that become refuse after being used and are thrown away. In certain way, the decision to turn a thing into a museum object gives it a new, tendentially eternal life. In this way things that were waste products in the Middle Ages and thrown into the latrine can become valuable testimonies to medieval life when they are in a modern museum. That is why it is difficult for me and many of my colleagues to take away the museal attribution of meaning that was given to an object – to use the ugly term: to “de-collect” it – unless its condition has deteriorated so far that it can no longer be conserved. As custodians of a future that we cannot know, we feel the obligation to preserve things for later generations of museum visitors, the importance of which only they might be able to recognise and define. The idea behind our acquisitions is therefore the question of which things in our present world we should preserve – a difficult decision at a time when every person, from baby to old age, will own an average of some 10,000 things in the course of their life.

The meanings we ascribe to an object are closely connected with the documentation on the provenance and “history” the object has gone through. Since the 1990s, when we became more conscious of the hundreds of thousands of Nazi thefts of cultural goods, the study of the provenance and the clarification of the legitimate acquisition of the objects in a collection became a central ethical requirement in the work of the museums, first laid down in the “Washington Principles” of 1998. This issue is about the reconstruction of unlawful contexts in the acquisition of objects and, if applicable, the initiation of restitutions to the heirs of those who had been bereft and in many cases murdered. A special case in our collection applies to the exponents that were transferred to us from the MfDG, which had sometimes come from confiscations by organs of the state. We know too little about these matters. But by means of research projects which we have initiated, we are attempting to gain fundamental knowledge of the background of these objects. In this way, collecting is related to ethical and legal questions which can be summarised in a single formula: We don’t want to have stolen goods in our collection.[4]

The collection is not only an annually expanding entity, it is above all the product of a never-ending process of discussion: What turns an object into an object of the DHM? What do we preserve from our present time and how do we deal with new types of objects such as original digital products? How do we achieve a long-term preservation of objects while also reducing the pollution of our environment? How do we tap into the vast knowledge that lies buried within the objects?

What must also not be forgotten: collecting in a museum is a very practical process, since it is about materials such a wood, plastic or paper, about improving the conservation methods, and about securing the objects against theft or other catastrophes. At the same time, it is an intensive, permanent exchange of ideas about societal aims, historical concepts and the fundamentals of historical judgement – a process that is carried on by every generation and in our museum is based on 200 years of collecting.

[1] Konzeption für ein Deutsches Historisches Museum – Überarbeitete Fassung, in: Deutsches Historisches Museum. Ideen – Kontroversen – Perspektiven, ed. Christoph Stölzl, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin 1988, pp. 609 – 636

[2] On the history of the museum, see most recently: Klaudia Charlotte Lenz, Matthias Miller, Zeiten und Seiten. 200 Jahre Bibliotheken im Berliner Zeughaus, Berlin 2022; Thomas Weißbrich, Ein Berliner Zeughaus und vier deutsche Geschichtsmuseen, in: Mitteldeutsches Jahrbuch für Kultur und Geschichte 32 (2025), p. 68-77

[3] Krzysztof Pomian, Der Ursprung des Museums. Vom Sammeln, Berlin 1988

[4] Vgl. Ethische Richtlinien für Museen von ICOM, hg. von ICOM Schweiz, 2010

|

|

Fritz BackhausFritz Backhaus is the director of the DHM department of collections. |