The collection of securities gives us insight into history

Lili Reyels | 8 January 2025

The blog series on the collection work of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) deals with core questions such as the decision for or against the acquisition of certain objects, the different ways in which they are found and acquired, the changing research questions posed by the objects in the collection, the provenance and origin of the objects, and many other aspects.

How and why did it come to an extensive and ongoing bestowal and cooperation contract between an institution of the federal government and the Deutsches Historisches Museum? Dr Lili Reyels, head of the DHM collection of financial and economic history until the end of 2024, examines this question based on one of the most spectacular extant collections of historical securities, the so-called “Reichsbank treasure”.

What is the “Reichsbank treasure” and how did it come about?

The fact that the major part of the German securities, stocks and bonds was located in Berlin-Mitte towards the end of the Second World War was due to a decree of the Reich Minister of Finance from 1942, according to which all such securities occurring in the German Reich were to be delivered to the German Reichsbank or the Prussian Staatsbank (State Bank) in Berlin. The securities survived the aerial attacks in the Berlin bank vaults until the end of April 1945, when the banking institutes in the centre of Berlin came under the control of the Soviet occupation authorities. After the head of the occupation of the city of Berlin had forbidden all banking business activities on 28 April 1945, the Allied Kommandatura decreed in August that all organisations and private persons in the area of Greater Berlin must deliver all foreign securities to the Berlin Stadtbank (City Bank), which was also located in Berlin-Mitte. It thus happened that when the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was founded in 1949, not only the vast holdings of the Reichsbank and the Prussian Staatsbank, but also almost all available securities in Berlin were located in the eastern section of the city. This huge stock of historical securities – the “Reichsbank treasure” – originally comprised more than 25 million stocks and bonds from Germany and 5 to 10 million other foreign securities.

Why is this collection of securities so interesting for the DHM?

These securities represent a considerable part of the capital assets of the German population from the period before 1945, virtually a time capsule containing the investments of the contemporaries in the past future of their time. Thus, alongside the industrialisation of the German Empire and the period of inflation, the Nazi dictatorship is also contained or documented in these holdings, and in this way it is possible, for example, to follow the Aryanisation in the area of registered bonds as well as the economic exploitation of the occupied countries and territories during the Second World War. Alongside the vast “economic mass”, the stock of paper securities is also interesting from an iconographic standpoint, because they contain national allegories, illustrations of historical business practices, and notes on company histories. Our knowledge of securities issues has been considerably expanded, particularly in regard to the time between 1930 and 1945.[1] Further findings could evolve in the area of the work of the GDR ministries. In 1951 the supervision of all bank vaults in East Berlin was transferred to the treasury administration within the GDR Ministry of Finance. In 1969 the Office for the Legal Protection of the Assets of the GDR took over the administration of these holdings and began bit by bit to tap into them. At the beginning of the 1980s, the so-called KoKo, the area of “Commercial Coordination” within the Ministry for Foreign Trade of the GDR, realised that the historical securities in the “Reichsbank treasure” could be used as a source to acquire foreign currency. By 1989 many securities had come into private hands. A planned sale of a major part of the stocks by the then head of the KoKo, Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, did not take place. But what then followed is a further chapter of German history.

After the reunification of Germany, the newly founded Federal Office for the Clarification of Unsettled Property Issues (BARoV), later Federal Office for Central Services and Unsettled Property Issues (BADV), attempted to return the securities to their former owners. Around 10,000 stocks were distributed according to applications that had been made. The BADV received the exploitation rights for the stocks that had not been claimed. In the case of the sale of historical securities, it is provided by law that the federal government should use the proceeds for the rectification of National Socialist injustice and for financial damages committed by the GDR and place this money in the compensation fund. Since 2003, the securities have been auctioned off in several batches.[2]

How did a cross sectional collection of “Reichsbank treasure” come to the DHM?

In the meantime the legal status of a large portion of the stocks and bonds has been clarified and most of the securities have lost their validity – have become worthless as so-called nonvaleurs. Alongside the legislative brief to exploit the securities, part of the federal concept for the DHM collection is to preserve the knowledge of the quantities of securities for the future and to display individual specimens of them for the public. In this connection, the BADV concluded an agreement with the DHM to exhibit a cross section of the papers in the museum. Even before 1990, both the East German Museum for German History (MfDG) and the DHM had already begun collecting historical securities as testimonies to industrial and political history – insofar as they had been on the market. After it became known that the BADV had taken the securities out of the collective custody of the former German Reichsbank, the DHM attempted to secure a cross section of the collection free of charge for the museum. The first portion of securities were transferred to DHM ownership in 2013, and since then, new batches have regularly been added, successively removed from the vault and prepared for transfer by colleagues of the BADV, and then selected and taken into our collection by the head of the DHM collection on financial and economic history. Therefore we no longer speak of a stock or supply – a more or less accidentally accumulated mass of securities – but instead of a collection that has been deliberately chosen and assembled in order to illustrate this dimension of German history.

Interesting examples in the collection of financial and economic history

The collection of securities gives us direct insight into history. For instance, the interest-free treasury bond of the German Reich issued in 1943 is an example of the engagement of the Reichsbank and debt management in the service of the wartime economy. Since the Reichsbank was under the direct control of Adolf Hitler from 1939 on, he was able to grant loans to the German Reich himself.

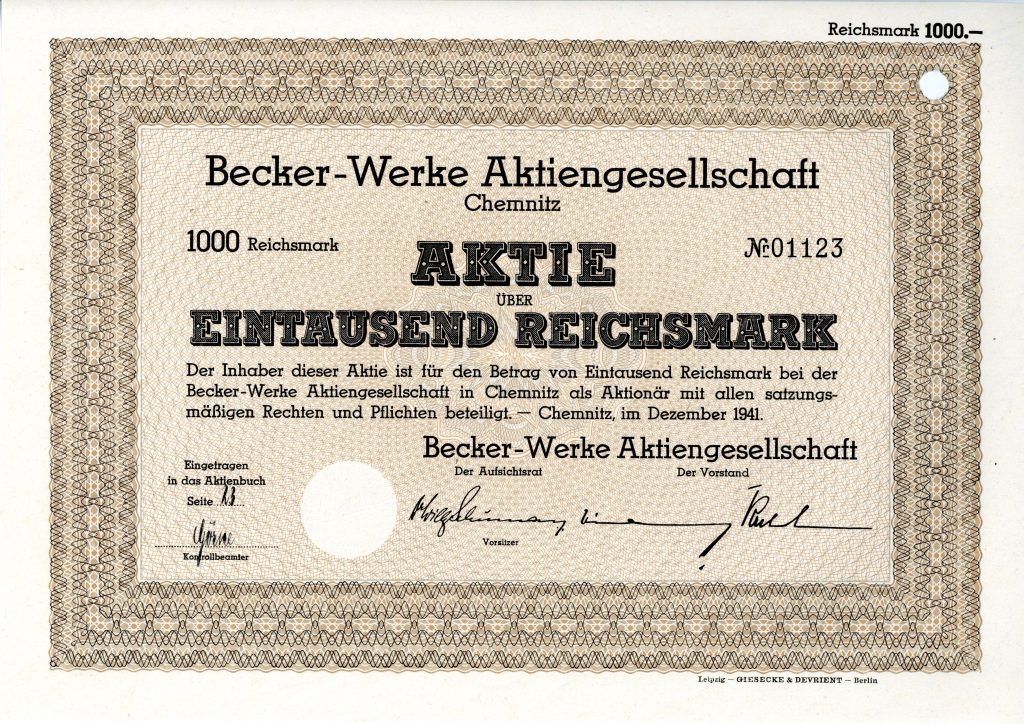

One the few direct pieces of evidence of the “Aryanisation” of Jewish enterprises in the handbook of the German stock corporations is the security of the Becker-Werke AG. Originally founded in 1883 as a glove factory, it became the OHG Eduard Becker Söhne company in 1924, which was then carried over into the Eduard Becker Söhne AG in May 1927. Alongside the two brothers Karl and Arthur Becker, the lawyer Dr Arthur Weiner was among the members of the supervisory board. After he was murdered, the brothers emigrated to Holland in 1933. In the course of the next years, the former chairman of the board, Fritz Kirch, and the procurator Otto Wolfsheimer were excluded from the firm. On 10 June 1938 the company was “aryanised” and renamed Becker-Werke AG.

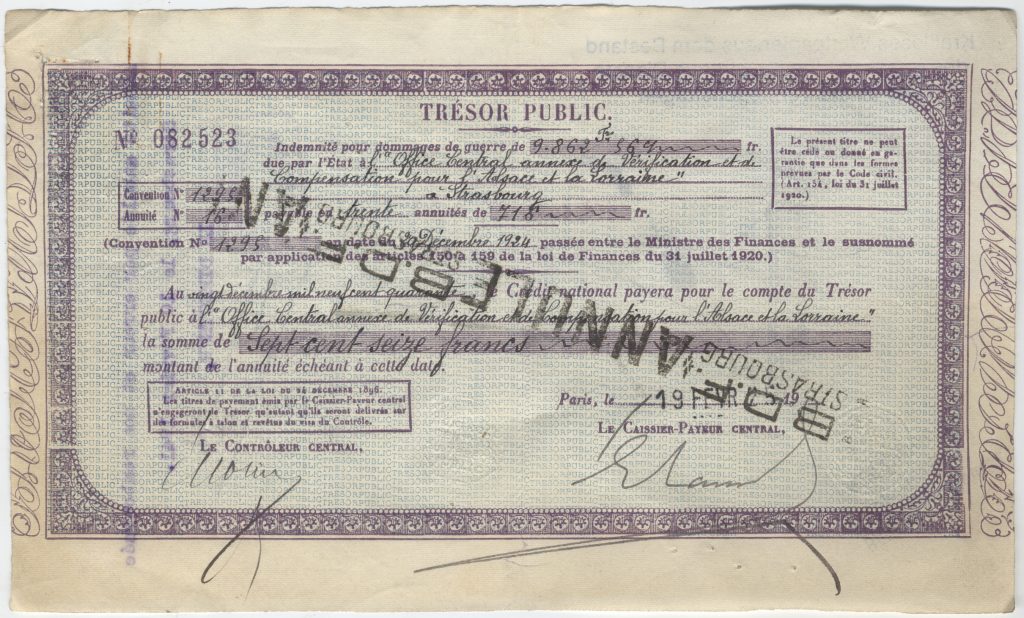

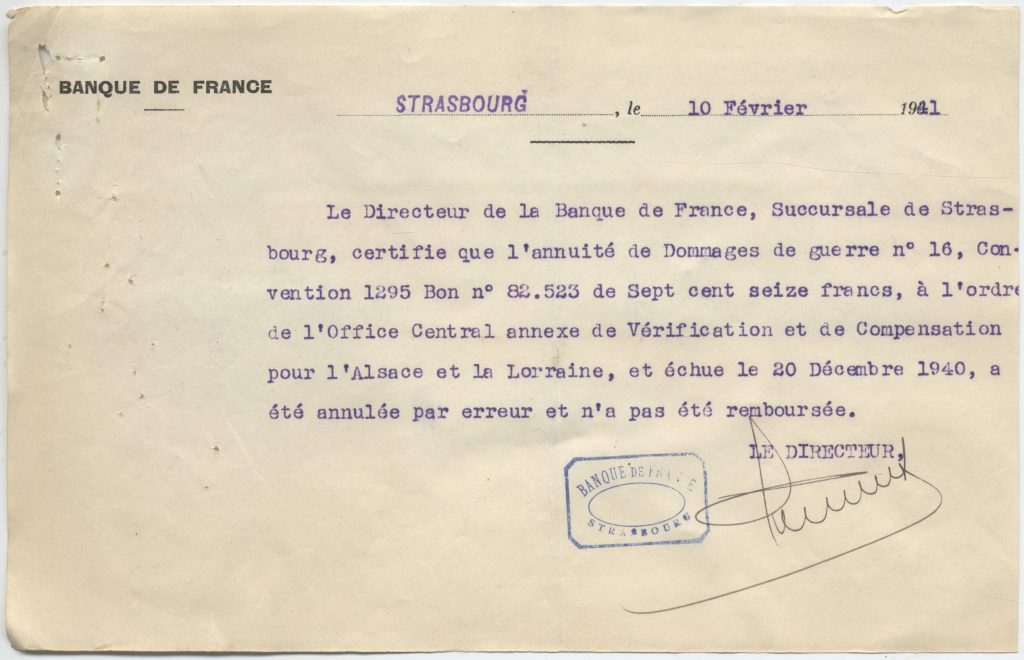

On 20 December 1940, the reparations from the First World War in regard to Alsace-Lorraine were due from the French Treasury, but a note in German states that the payment “[can] not currently be honoured” – “all payments from France [are] blocked”. This was a consequence of the German occupation of France since summer 1940, which had the result that the French economy and state finances were placed in the service of the German Reich.

______________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Cf. Christian Stoess: Der Reichsbankschatz, in: Vorträge zur Geldgeschichte im Geldmuseum 2, Frankfurt a. M. 2005, pp. 55-75.

[2] Constanze Budde-Hermann: Der Reichsbankschatz. Das Schicksal der Reichsbank, Wertpapierbereinigung und Perspektiven der Sammlung, in Archiv und Wirtschaft, 53, Jg. 2020, Sonderheft, pp. 50-56.

|

|

Dr. Lili ReyelsDr Lili Reyels is the former head of the DHM collection on financial and economic history |