A talk about the Enlightenment with the literary Enlightenment author Angela Steidele

19 February 2025

“Unfortunately, the Enlightenment soon stepped on its own foot. But before that it had already given us the instruments with which to think.”

Between the covers of her novel Aufklärung (Enlightenment) Angela Steidele finds room not only for the characteristics and diversity of topics of the Enlightenment, but also for its distinct features, which she portrays with love and humour in the conversations and thoughts of the novel’s characters. At the same time she tells us something about our present.

On the occasion of the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”, Stephanie von Steinsdorff spoke with her about literary, philosophical and musical counterpoints as characteristics of the Enlightenment, about language in general which “cannot be overestimated in its importance”, about emancipation, and about the idea that one can “take a wrong turn” as happened in the 19th century, and what that has to do with enlightenment and our present day.

Frau Steidele, what fascinates you about the 18th century?

I am in love with the eighteenth as the century of worldly wisdom, the sciences, optimism and awakening, and the readiness to accept new thinking. And I don’t like the 19th century, for it made a wrong turn, repressed women again, invented the nation state. Many of the good things we can draw on today have to do with the 18th century, and much of what we should discard has to do with the 19th century. This is certainly an extremely simplified statement, for the Enlightenment soon stepped on it own foot. But before that it had already given us the instruments with which to think, with which we can recognise why the Enlightenment betrayed itself. And this added value of critical thinking – this is the gift that the 18th century gave us and where we can continue to pursue our own thoughts.

At what point do you think it went off on a manifestly wrong tangent?

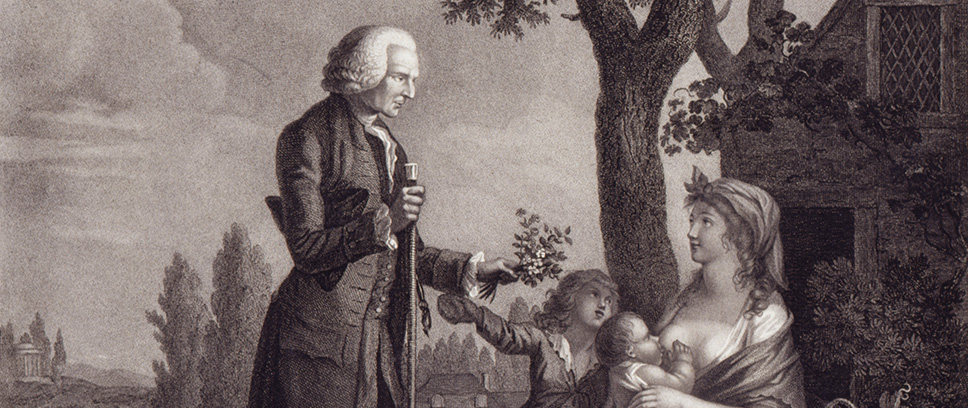

Rousseau marks a decisive caesura. With secularisation the male representatives of the Enlightenment noticed that they had run out of arguments as to why the woman should be subject to the man: If there’s no God, there’s no Eve to clean up after Adam and give him a pretty home – like Rousseau’s Sophie for Émile. The early and middle Enlightenment, by contrast, knew the ideal of the educated gentlewoman. For one or two generations the window was wide open, and an Emilie du Châtelet, an Olympe de Gouges, a Luise Gottsched could peer through that window, or a Laura Bassi in Italy. After Rousseau and his epigons, every woman who publicised in the 19th century had to apologise in the preface: No, no, my husband is well taken care of, my children are happy after I’ve finished washing up, and in my last leisure hours I’ve managed to write this novel. It’s agonizing.

In your novel you describe Johann Sebastian Bach’s music as Enlightenment music, although Bach is conventionally known as a Baroque musician. Does Bach’s music contain a feature that is characteristic of the Enlightenment?

I understand Bach as an Enlightenment musician. With the Tempered Clavier and the Art of the Fuge, for example, he presented essays, but in tones, not in words. The central element is the counterpoint, where there is not one main voice and the rest is only accompaniment, but rather all voices contribute together to the thought of the music: Sometimes the tenor steps forward, sometimes the bass, sometimes the soprano, or then the duet with the middle voices forms the central element. In this contending, questioning, answering, further thinking, adopting, one can recognise a musical metaphor of the Enlightenment. We are used to the light metaphor, but it is only a visual metaphor – counterpoint is the musical metaphor of the Enlightenment. And Bach’s music, i.e., the counterpoint, inspired me in particular to the composition of the novel itself, which is also counterpointed, in other words, polyphonic: many-voiced, rich in figures, with numerous scenes where a lot is spoken and debated, and where the thought is carried on jointly. The novel also doesn’t have one distinct central character. At the beginning Dorothea Bach says that she is writing a book about Luise Gottsched, but actually in the course of the book she might become the main character herself, because as the narrator, she certainly has the principal voice. These are all attempts at a literary adaptation of counterpoint.

Why did you choose the time of the Enlightenment for your novel and in what way does the female perspective play a special role?

I have been singing and playing Bach all my life and in my dissertation almost 25 years ago, I had to do with Luise Gottsched. Even then it was clear to me: Johann Sebastian Bach and the Gottscheds lived next to each other at the same time in Leipzig for thirty years. It was a time when Leipzig was the centre of the German-language Enlightenment. But we are so used to understanding Bach as a Baroque musician. How does that go together? How does the St. Matthew Passion fit into the Enlightenment? I knew that there was a fantastic story in there somewhere, but I could only dig it out when I was in despair about our times, when I encountered the neo-irrationalisms that we’ve been subjected to in the last ten or fifteen years. Twenty years ago, you didn’t have to explain why vaccinations are sensible. On the contrary, worldwide we were really glad that illnesses had been eradicated. And all of a sudden we have to spend our valuable time to justify things that science has already clarified for us. – For my novel it was clear to me that it could only be written from the viewpoint of a marginalised figure who has dropped out, who the enlightened thinkers had not paid attention to. I could have chosen a Jewish or a Black perspective to think about the Enlightenment and not to repeat its mistakes. But I chose a female figure, because I have greater access to a feminist character.

The first-person narrator Dorothea Bach adopts a supplementary voice to the story that opposes that of Johann Christoph Gottsched. Is that an expression of protest in literary form?

Yes. Gottsched led a marriage, very exceptional, as an intellectual tandem– according to our standards Luise Gottsched should have stood on the title page of his books. At the same time, the biography that he wrote about her after her death is outrageous from today’s point of view, because he writes more about himself than about his wife. This outrage was also once felt by the private Angela Steidele.

By the use of “gendering” [in the German language] you form a bridge from the 18th century to today. Why did you use modern gendering in your novel?

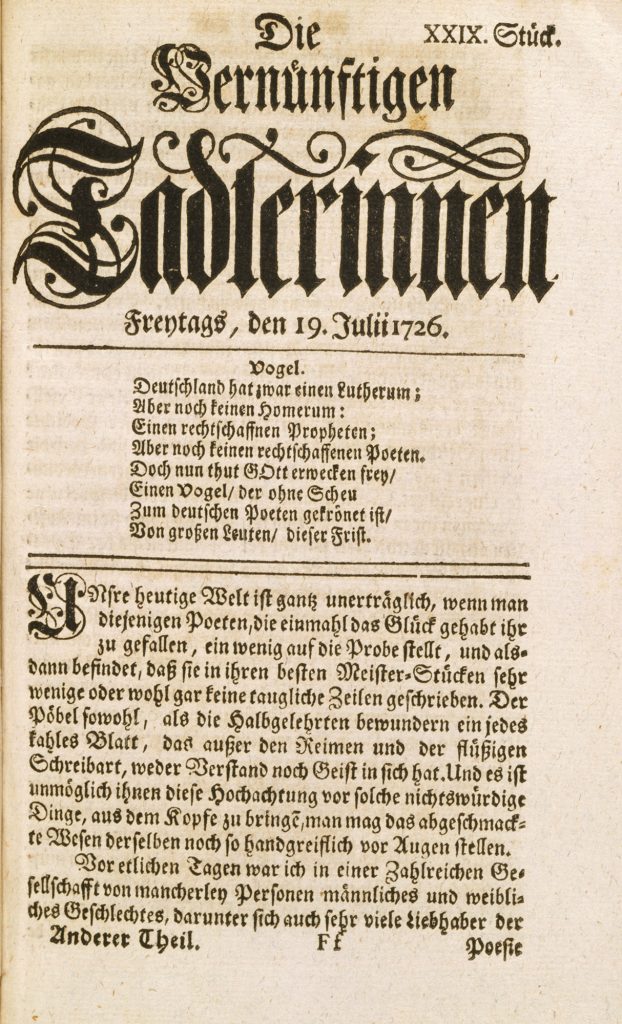

The importance of language can not be overestimated. Language as a system of references always means something else, it doesn’t stand for itself and is not a neutral instrument. For me it was a devilish treat to mirror our time in that of the past, because the 18th century “gendered” more or differently than we do – just savour that for a moment. Female surnames like “Madame Gottschedin” or “Madame Bachin” were gendered. That is historical reality, and the place in the novel when Christiana Mariana von Ziegler, Luise Gottsched and Dorothea Bach quarrel about the use of language in the “Vernünftige Tadlerinnen” (Reasonable Female Critics), it’s all in the original: “Verwandtinnen” (female relatives) or “Bekanntinnen” (female acquaintances) are words that I found there. I wanted to get that across in the novel “Aufklärung. Ein Roman”: a joy in speaking. Joy in well-meaning speaking is joy in thinking, and please let us do it amicably: it is possible. When hate gets into the act, it is no longer about language. It’s always about something else.

What does it mean in our current era to draw on the thoughts of the Enlightenment?

If we take the ideals of the Enlightenment seriously, we have to develop our democracy further and make it happen that all people are equal. Unfortunately, we are again experiencing a time when people are becoming less equal, worldwide, but also in our own society. Here you can get sad inspiration from the 18th century. For me part of the plight of the Enlightenment is that the enlightened thinkers liked to fight against irrationality, but they liked even more to fight against other enlightened thinkers. Hate is no invention of our time, even though it has taken on special forms and degrees. But to battle against each other and clobber each other with the most dreadful pamphlets – that’s unfortunately something that people back then could also do. The medium and the access to forms of publication have changed, but unfortunately the hate has not.

Angela SteideleAngela Steidele thinks in novels, biographies and essays about history as the present time, about art as science and love as provocation. Research scientifically – write literarily is her hallmark. Her latest work, Aufklärung. Ein Roman (2022), was nominated for the Prize of the Leipzig Book Fair (category: fiction). In 2023 she was awarded the Klopstock Prize for New Literature for the body of her literary work to date. |