Chauvinism in Sheep’s Clothing. A look at the women of the Enlightenment and how they have influenced us

Harriet Merrow | 6 March 2025

When we think of the Enlightenment, we think of the demand for equality and emancipation. But did that also apply to women? The answer is ambivalent: on the one hand, we find a chauvinism pretending to be enlightened, on the other, strong women who carved out a place for themselves in society. On the occasion of International Women’s Day 2025, Harriet Merrow, project assistant on the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”, focuses on the different roles of women in that era.

The question “What is Enlightenment?” stems from a footnote in a critical contribution about civil marriage in the Berlinische Monatsschrift from December 1783. It was posed by the conservative theologian Johann Friedrich Zöllner (1753–1804). In his essay “Is It Advisable to Sanction Marriage through Religion?” the pastor warned against the threatening decline of morals if the wedding of two people wanting to get married no longer takes place as a religious act (but is sanctioned only by civil law) and asks in a footnote: “What is Enlightenment? This question, which is almost as important as: What is truth?, should be answered before one begins to enlighten! And I have not found it answered anywhere!”

The attempt to introduce civil marriage mostly had to do with the enlightenment ideal of religious tolerance (in this form of marriage, couples could be of different confessions or even different religions). But to see the marriage contract as a contract sanctioned by the state could also have useful implications for the wives. A wedding that was no longer conducted “in the eyes of God” could also be separated without divine blessing and that would mean greater freedom in getting divorced. “Mutual aversion” or “non-conformity of character”[i] now belonged to the grounds for separation and a “relationship based on partnership”[ii] between the married couple was aspired to. To consider oneself enlightened in the 18th century also meant to express one’s understanding of marriage rights and obligations in accord with the “high civilisational standard of the age.”[iii] So, is the Enlightenment with its debates about civil marriage the great leveller between the sexes? That is not quite the case. The woman as partner in marriage and life was idealised in the educated bourgeois milieu as a “cultivated” sparring partner, but she did not achieve partial – much less a complete – equal status.

Instead, the leading Enlightenment thinkers saw the woman as standing “outside of the bourgeois society of mature, equitable citizens”[iv]; the ideal of the coequal companion was performative and was very likely found more appealing in theory than in practice. The good wife should receive a basic education so that she could hold her own in conversation and be amusing – but her ambitions should seldom go too far. In the satirical copperplate engraving “The Learned Lady” by Johann Heinrich Ramberg (1763–1840), the artist jokingly exaggerates the risks that a distraction from the household and care of the children though a pursuit of learning would bring. The example of civil marriage and the role of women in times of the Enlightenment clearly illustrates the conflicting priorities that characterised the view of the equality of man and woman in this epoch. One could speak of a chauvinism posing as enlightened or a chauvinism in sheep’s clothing. At the same time – and this, too, distinguished the Enlightenment – there were women who would not accept the status quo and fought for their place in society.

“What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”, which is named after Zöllner’s meanwhile world-famous, oft quoted footnote question, explores this social context and presents stories of women in all rooms of the exhibition – women are not just accidental products of the 18th century: without them the Enlightenment can “only insufficiently be depicted and understood.”[v] In this way the exhibition reflects on a purely structural level the fact that women were able to make their mark in this philosophical, largely male-dominated age in many different ways. Visitors will find enlightened female protagonists not only in the section “Gender Models”, but in all other rooms of the exhibition as well, including “The Rule of Reason”, “The Search for Knowledge and the New Science” and “Statesmanship and Political Liberty”.

Among the academically engaged women presented in “What is Enlightenment?” – whose lives need to be much more intensively researched – are, for example, Émilie du Châtelet (1706–1749), Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier (1758–1836), and Dorothea Christiane Erxleben (1715–1762). While the Marquise du Châtelet devoted her life to Newton’s physics and translated, annotated, and brought his works to the French public, Marie-Anne Lavoisier participated in the chemical experiments of her 15-years-older husband Antoine. With her detailed documentation of the experimental setups in his laboratory and translations of scientific publications, she contributed decisively to the wording and empirical verifiability of the findings even after his death. Dorothea Erxleben, who was only allowed to study medicine if accompanied by a male relative, addressed herself in 1741 to Friedrich II (1712–1786) with a request to be allowed to study at university. At his behest she was admitted to the Reform University in Halle. More than a decade later, at age 39, she submitted her dissertation and in 1754 became the first woman in Germany to get her doctorate in medicine.

The exhibition also deals with women involved in the arts during the Enlightenment period, including the poet Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784), the author Luise Gottsched (1713–1762), and the painter Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782). The poetry book of the repeatedly discriminated, enslaved Phillis Wheatley, which appeared in 1773, made her the first author of African origin to have published in America under her own name.[vi] The “Gottschedin”, as Luise Gottsched was known in Germany, already published several theatre plays under her own name in the first half of the 18th century. What’s more: literary research now assumes that she actually wrote some of the works of her husband, Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766) – for example, numerous passages in the moralistic weekly “Die vernünftigen Tadlerinnen”.

The artistic career of Anna Therbusch – particularly in a time when it was hardly possible for women to be admitted to art academies – is remarkable. The Berlin artist even received commissions from the European nobility, and from the time she was taken into the Académie Royale in Paris in 1767, she signed her works “Peintre du Roi de France”, “Artist of the French King”.

Alongside scientific pursuits, it is often social change that is closely connected with our image of the Enlightenment. And so it is hardly surprising that the time was also marked by sociocritical, politically engaged female thinkers. Among them, for example, are the French revolutionary Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793) and the English women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797). De Gouges not only took a stand for the equal rights of man and woman, but is also an example of a white woman who fought against the racism of her time in her writings and theatre plays. She also called for the introduction of a divorce law.[vii]

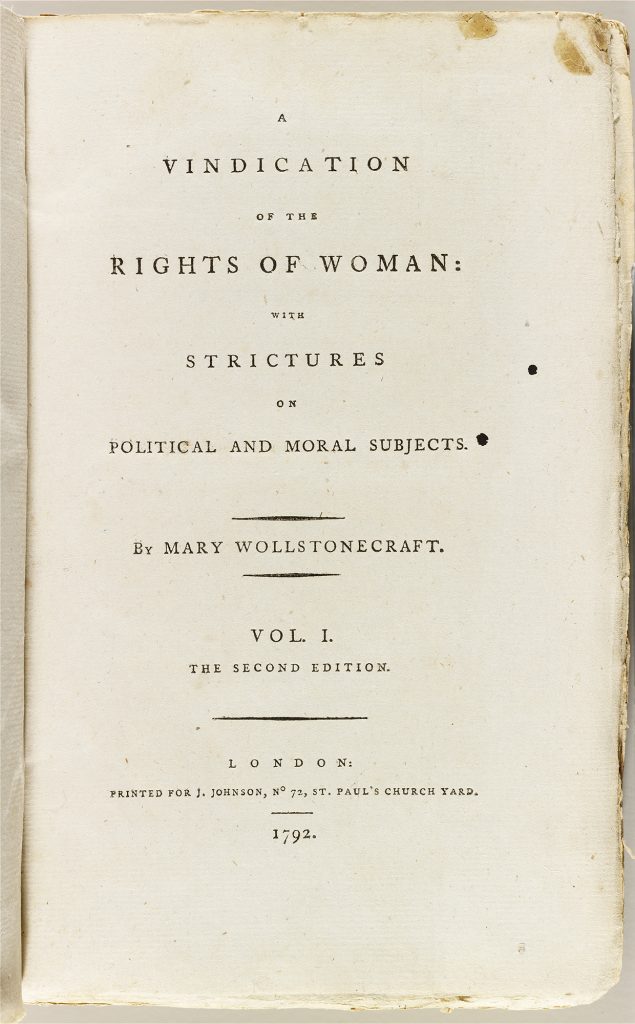

Mary Wollstonecraft, whose principal work from 1792, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, is cited at the beginning of the exhibition, also took a strong stand against reducing women to the role of the devoted wife – with or without the right to get a divorce. The noted philosopher and translator Mary Shelley, also known as the author and “mother” of Frankenstein, lived for years with the father of her first child without getting married. She only experienced the start of her influence on the struggles for equal rights in the European sphere, since she died early of childbed fever. Her argumentation that women have a capacity for reason equal to that of men influenced the following generations.

The women of the Enlightenment had a heavy load to carry in an era of chauvinism in sheep’s clothing and could seldom rely on gaining the recognition they deserved for their work. Thanks to decades of research by (often explicitly feminist-motivated) historians, their stories can still be understood today and form part of the fundament of the modern women’s movement, of which an internationally networked group of women socialists introduced the first International Women’s Day in 1911, nearly a century after the fading of the Enlightenment cause. It is a sad irony that the two countries, France and England, which with Wollstonecraft and de Gouges brought forth the most radical champions of women’s rights, were comparatively late in introducing women’s suffrage, namely in 1928 in Britain and 1944 in France.

[i] Buchholz, Stephan: „Ehe“, in: Schneiders, Werner (ed.), Lexikon der Aufklärung, München 2001: pp. 87–88.

[ii] Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara: Die Aufklärung, 5. Aufl. Stuttgart 2021: p. 147.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Meyer, Annette: Die Epoche der Aufklärung, 2. Aufl. Berlin 2018, p. 189.

[v] Ibid., p. 188.

[vi] Cf. Bissig, Florian: „Einleitung“, in: Wheatley, Phillis: Nie mehr, Amerika! Gedichte und Briefe. Aus dem Englische von Florian Bissig, Berlin 2023, p. 13.

[vii] Cf. Stokowski, Margarete: „Freiheit, Gleichheit, Gerechtigkeit“, in: De Gouges, Olympe: Die Rechte der Frau und andere Texte: Stuttgart 2022: pp. 74–75.

|

|

Harriet MerrowHarriet Merrow is the project assistant at the Deutsches Historisches Museum for the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the Eighteenth Century”. |