Stagecraft without electricity in the time of the Enlightenment: Dalberg’s stage model

Irmgard Siede | 19 March 2025

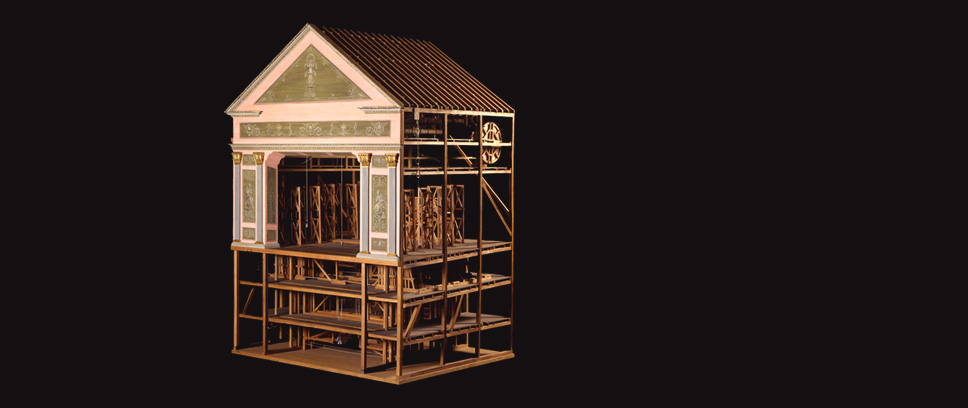

While stages now operate with the most modern technology to captivate the audience and the senses, the 18th century was also not without striking mechanical stage effects. The so-called Dalberg stage model, which is currently on loan from Mannheim in the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”, gives fascinating insights into the sophisticated stage machinery of that time. Dr Irmgard Siede from the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim (rem) tells the story behind the stage model.

Contemporary theatre has to measure up to the flood of medial images, the quick perception of pictures, and the omnipresence of special sound, smell, and light effects. To this end theatres have created elaborate stage technologies that make use of modern sound equipment, lighting apparatus and powerful motors. It’s hard to imagine, but by building and furnishing transformable stages and special effects thanks to sophisticated stage mechanisms, this was also possible to achieve at the end of the 18th century. A prime example of this is the Dalberg stage model, which is the central object of the theatre exhibition in the rem in Mannheim.

The model is named after the Dalberg family, a member of which was Wolfgang Heribert von Dalberg (1750–1805), the first intendant, or artistic director, of the Mannheim National Theatre. The urban layout of Mannheim is based on the famous squares (Quadrate). The Dalberg family first lived in a palace in Quadrat B 1, 10. Wolfgang Heribert von Dalberg rented a residence in Quadrat N 3, 4, probably in 1782, known today as the Dalberg House. He held high political offices: from 1775 as “Obrist-Silberkämmerling” (city chamberlain), in 1778 vice-president of the exchequer, from 1780 member of the Privy Council, which gave him insight into the governmental activities of the Electoral Palatinate, after which he served as president of the High Court of Appeal, the highest judicial body of the Palatinate, from 1791 to 1803.

With an electoral rescript (decree) from 1 September 1778, Dalberg was appointed superintendent of the Mannheim “National-Bühne”, which had already opened in January 1777. Thus, he was the first Intendant, or artistic director, of the house and remained in this capacity for almost 25 years, until 1803. In 1778 Dalberg had also become the superintendent of the Kurpfälzisch Deutschen Gesellschaft (Electoral Palatinate German Society). He was already active as a playwright and translator of foreign-language plays, because plays were presented in the National Theatre in the local language, thus adding to enlightenment through vivid experience. This innovative format, which was supported by the absolute prince Carl Theodor (1724–1799), was accompanied by a further innovation: A theatre committee – consisting of the intendant, actors and other persons – held discussions about theatre, which were recorded in the minutes of the sessions for eight years, from 1781 to 1789. It is very likely that they also discussed stage technology. The public continually placed higher demands and the theatre business, including stage technology, became more and more elaborate and expensive. At the same time, the “look behind the scenes” and the stage machinery was increasingly depicted in graphics and pictures. Such graphic prints usually found their way into encyclopaedias. In the theoretical discourse of the late 18th century, advanced stage technology also served as practical training in the theoretical mechanics of the Enlightenment.

There is no definite record of where the model stood in 1800. According the Aschaffenburg tradition it came from the possessions of Dalberg family. Mannheim acquired it in June 1929 from the town of Aschaffenburg for the collections of the Mannheim Palace Museum. As with a peep box, one looks into a stage house with a classicistic proscenium (the part of the stage between curtain and orchestra) and a wooden floor, the famous “planks that (should) rule the world”, which is the surface on which the play takes place. The stage is slanted slightly upwards. The perspective would normally be to the prospect, or back-cloth. The proscenium hides the upper machinery and the backdrop cars, or chariots, which are lined up on both sides. In the model, the lower machinery is three-storeys high. If you walk around the model, you can see five backdrop cars on each side, into which scenery flats, usually covered with painted canvas, can be hung. The frames extend through slits to the floor and can slide back and forth on tracks in the lower machinery. In the upper machinery a construction with a vertical main shaft and wheels, drawstrings, and weights can be seen. It serves to move the curtain, the soffits (short scenery pieces hanging from the ceiling), the stage prospect, and the scenery. The backdrop cars as well as the back prospect and soffits were connected by rope through a clever system to a central winch called the main shaft or axle tree. In this way the stage could be completely changed in a matter of seconds. Optical effects and wave movements could be created, as were noises by means of a wind machine. All this aimed to fill the audience with wonder. The scenery aisles also functioned as storage areas for the props and indirectly as lighting for the stage. Oil lamps could be hung on the frames.

In the early 20th century, the baroque stage technology was still largely extant in the Schlosstheater in Schwetzingen. Sometime before 1927 it was described by the theatre scholar Kurt Sommerfeld. This proved that the Dalberg model really represented machinery that had been built in those times.

When on 13 January 1782 Schiller’s play “The Robbers” premiered under Dalberg’s directorship in the old National Theatre in Quadrat B 3, the stage set was changed many times with the help of such mechanisms.

Dr Irmgard SiedeDr Irmgard Siede is an art historian and technical head of the collection in the rem in Mannheim. Since 2019 she has been responsible for the Mannheim theatre collection, which represents one of only five such collections in the German museum landscape. |