Mata Hari, the Beautiful Spy

Mata Hari: if she lived today, she might well be a YouTube star. Born Margaretha Geertruide Zelle in 1876 in the Dutch town of Leeuwarden, she went on to forge a new identity for herself and became highly successful at selling that identity as a brand. The name “Mata Hari” still resonates to day. A hundred years after her death, it still evokes a unique combination of eroticism and espionage.

All the sources agree – and, it should be noted, every photograph we have of her confirms – that Mata Hari was a beautiful woman with that “certain something”. With great resourcefulness, she found a way of using her beauty and allure to survive in a world dominated by men. Yet the path she chose led her ultimately to face a firing squad of French soldiers. On 15 October 1917, in a field near the Château de Vincennes, she was executed as a German spy.

Just over forty years earlier she was born the daughter of a milliner, from whom she inherited a certain talent for showmanship and – one might even say – imposture. Her father enjoyed periodic spells of prosperity from dabbling in speculation but when he became permanently impoverished, Margaretha was expected to stand on her own two feet. At 15 she was sent to a pedagogical institute to train as a kindergarten teacher. It was a career for which, as everyone who knew her agreed, she was completely unsuited.

From this situation there was only one escape: marriage to a well-to-do man. Margaretha replied to an advertisement for a bride placed by a very much older army officer by the name of Campbell MacLeod. She married him and travelled with him to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), where she fell in love with and soaked up Indonesian culture. Her marriage, however, was a failure. Of the two children the couple had together, one died in Asia from poisoning; the other returned with her parents to Europe in 1903 and, after their divorce, lived with her father.

A successful seller of dreams

And what did Margaretha do? She went to Paris – with no money, no education and no family. But it was here that her talent came to the fore. She invented a completely new identity for herself; she became a fictional character: Mata Hari, a Javanese princess. In Paris, her novel and exotic veil dance soon made her a star by playing to the erotic fantasies of white men. For a few years she was able to make a good living, sometimes finding patrons who supported her both on and off stage. Soon, however, her style of dance began to be copied by other women, and Mata Hari found herself increasingly obliged to supplement her income as a dancer by selling her favours.

When the First World War began in 1914, Mata Hari broke off a tour of Germany. As a citizen of a neutral country, however, she was still able to travel, and over the next few years this became an asset that opened new avenues of income. In September 1916, the French secret service recruited Mata Hari as a spy – she was to entice secrets out of German officers. But, unbeknown to them, the dancer had already long since been in the service of the Germans and was eavesdropping on her friends among the Allies. In February 1917 she was arrested by the French military and, after a swift trial, executed.

From dream-seller to scapegoat

The reports which Mata Hari had delivered to the secret services contained hardly any valuable information. Nevertheless, she was obliged to pay for her activity as a double agent with her life. Her death had another, symbolic purpose: it was hoped that her execution as a spy would instil confidence among the French people. In 1917 things were not going well for the French army; the spring offensives on the Chemin des Dames had failed and the French military had been shaken by mutinies. Victory was still nowhere in sight and, so too, neither was an end to a war which had already dragged on for three years. Spies and secret agents, secretly working underground against France, provided a welcome explanation for military failure; one which was readily believed and perpetuated among the wider population. As had already happened in 1914, during the first months of the war, France became gripped by a paranoid fear of espionage. It was for this reason that Mata Hari was condemned after a trial lasting only one day – it was absolutely imperative that the French authorities be seen clamping down on spies.

The danger posed by spies was far from imaginary. The First World War was also a war between rival secret services. As in every modern war, information could have a decisive influence on theoutcome. The fact that Mata Hari spied for both the Germans and for the French is part of her enduring appeal. Her life mixed sex with suspense, a combination which is still successfully exploited by spy films all over the world.

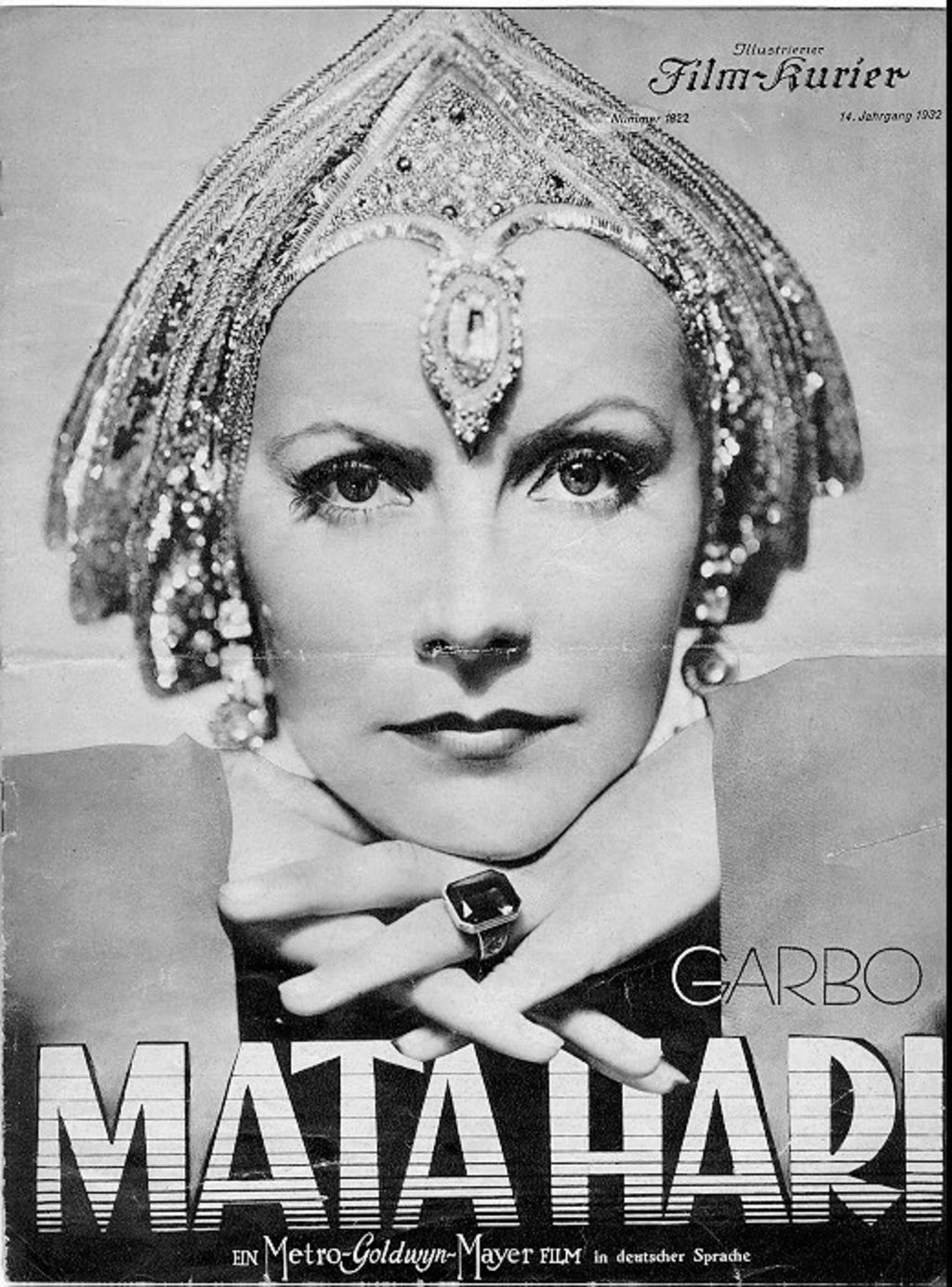

The image of the seductive spy, living a perilous life between warfronts, proved stronger than death. Mata Haris’ legend began to take shape immediately after her execution: rumours circulated that she had managed to escape death, thanks to her powers of seduction. It was the films that were made about her life after the war, however, that really cemented her legend. In 1920 Asta Nielsen starred as the spy in a German silent movie, and in 1927 another German film followed, this time with sound. But it was the film of 1932, with its masterly portrayal by the “divine” Greta Garbo, that made Mata Hari truly world famous.

Film programme for “Mata Hari” with Greta Garbo, Illustrierter Film-Kurier Nr. 1822, Film-Kurier GmbH, Print, Berlin, 1932 © DHM

Mata Hari’s life has been reinterpreted in many different ways. In his 1964 screenplay for the film “Mata Hari – Agent H21”, in which Mata Hari is played by Jeanne Moreau, Francois Truffaut highlights the fragility of her personality. In other interpretations, for instance the 2017 film “Tanz in den Tod” (Dance into Death), shown this summer by the German public broadcaster, ARD, she is portrayed as a woman who – like her boss in the German secret service, “Fräulein Doktor” Elsbeth Schragmüller (1887–1940) – has the toughness to succeed in a male profession.

One thing remains clear though: even a hundred years after her death, she is still nothing less than a legend.