Austria’s “Anschluss” with Germany in 1938

The situation for German-speaking Jews had worsened even prior to the pogroms of November 1938. Known as the “Anschluss”, Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938 led to a considerable increase in violence and public discrimination against Austria’s Jewish population. The historian Miriam Bistrovic, who works for the Berlin branch of the New York-based Leo Baeck Institute, traces the events of these crucial few days in an article she has written for this blog. She is also one of the people behind the virtual calendar, 1938Projekt – Post from the Past, where you can learn more about the experiences of Jews at the time of the “Anschluss”.

“The president of the Republic of Austria has asked me to communicate to the Austrian people that we will not put up any resistance to violence,” announced Kurt Schuschnigg in a radio address on the evening of 11 March 1938. He strenuously denied claims that uprisings were taking place or that the government was no longer in control of the situation. A few hours previously, he had resigned as Austrian chancellor and was now asking both the military and civilian population to refrain from any form of resistance in the event of a German invasion.

Panorama Vienna, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Vienna Jewish Community Collection AR 2432, F 24082.

Austria had been put under increasing pressure during the previous months. Following the Berchtesgaden Agreement of 12 February 1938, the country was forced to acquiesce to Adolf Hitler’s demands that Arthur Seyss-Inquart be appointed interior and security minister, and for Austrian National Socialists to be included in government. However, Kurt Schuschnigg had on 24 February 1934 spoken in defence of Austrian independence to the rapturous applause of his audience in the national parliament in Vienna, uttering the call-to-arms: “And therefore, comrades: until death: red-white-red” [the colours of the Austrian flag]. The tense political situation between Germany and Austria escalated when Kurt Schuschnigg announced on 9 March 1938 that a plebiscite on the future independence of the country would be held the following Sunday. The procedural irregularities of the planned plebiscite gave his opponents an opportunity to act. Germany gave Austria a deadline to respond to its ultimatum, demanding that the German Reich be given a say in determining the Austrian government, and threatening to send in troops if the terms were not met. As is clear from the speech broadcast on the Austrian RAVAG radio network, neither Kurt Schuschnigg nor President Wilhelm Miklas were in any doubt about Adolf Hitler’s determination to make good on his threat. Schuschnigg therefore ended his powerful address on 11 March 1938 with a heartfelt wish: “God protect Austria”. While the former chancellor continued to enjoin his compatriots to “wait and see what decisions are made over the coming hours”,[1] Austrian National Socialists were already asserting their control over public spaces. In a hurried display of obedience to the Nazi regime, they raised swastikas on public buildings and attacked Jews openly on the street. “There is now a new day of mourning to add to the annals of our history,” wrote the Jewish law student Paul Steiner (born in Vienna in 1913) in his diary that very evening.[2]

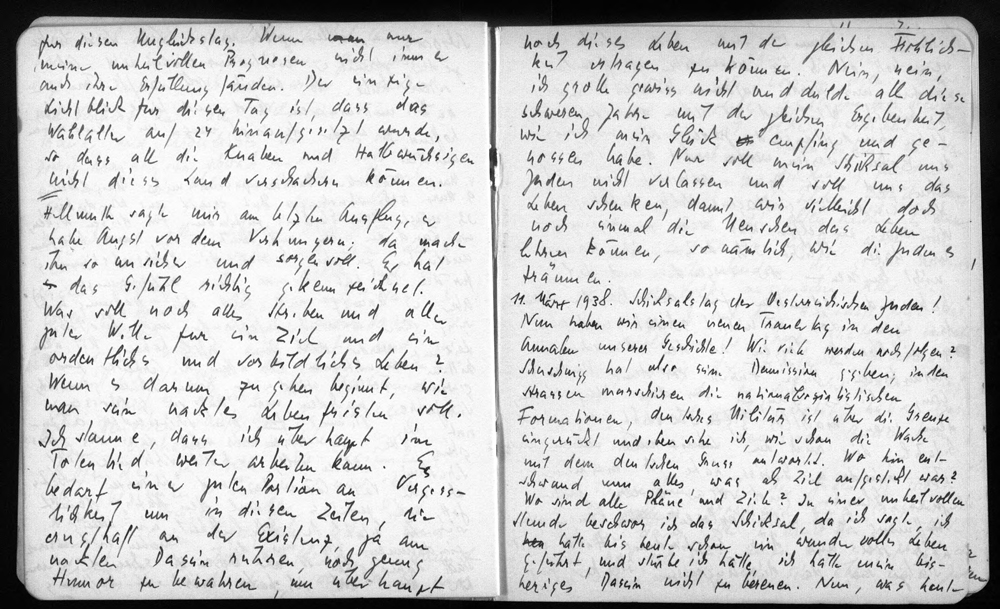

Diary Paul Steiner, Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin, Paul Steiner Collection AR 25208, Diary No. 7, February 2, 1938 – April 18, 1939.

German troops cross the Austrian border

The German military had by this stage already received orders to invade. In the early hours of 12 March 1938, German troops crossed the Austrian border. In accordance with Kurt Schuschnigg’s resignation speech, the Austrian army offered up no resistance. Indeed, the same applied to large sections of the civilian population on encountering the Wehrmacht. According to the reports of eyewitnesses, the arriving soldiers were instead treated to a joyous welcome.

Escalating violence and public discrimination

Following Adolf Hitler’s arrival in Linz on 13 March 1938, the “Law on the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich” (RGBI. I 1938, p. 237) was submitted. Wilhelm Miklas refused to give the law his presidential assent and resigned, after which the power of disposition passed to the recently appointed chancellor, Arthur Seyss-Inquart. It was his signature that passed the act into law. Austria’s “Anschluss” with the German Reich had been officially implemented.

This was immediately followed by attacks on Jewish men and woman. There was a wave of looting and “wild aryanizations”, a term used to describe the indiscriminate theft of businesses and private property from their Jewish owners. From mid-March, businesses and department stores placed newspaper advertisements announcing that they were now “Aryan” – Jewish employees having been summarily dismissed after many years of service. The “Act for the Defence of Public Servants” of 15 March 1938 meant that anyone categorized as a Jew by the terms of the Nuremberg Laws was dismissed from the civil service, and so deprived of what they had assumed to be financially secure livelihoods. Physical violence and public humiliation became an “everyday experience” for Jewish Austrian men and women. There was a sudden surge in the suicide rate. Above all, it was the notorious “scrubbing corps” (Reibpartien), in which Jews were forced to clean the streets with brushes – or even their bare hands and caustic soap – that became etched in survivors’ memories. These public humiliations were conducted in the presence of gleeful onlookers and often in the immediate vicinity of the affected person’s home or business. Those initiating the violence included close neighbours of the people being humiliated, whom they sometimes accosted on the street and spontaneously coerced to join one of the “scrubbing corps”.

Advertisement of the NSDAP for the plebiscite about the “Anschluss” of Austria, Berlin 1938 © DHM

On 10 April 1938, a plebiscite on Austrian independence was held to coincide with the last parliamentary elections to the Reichstag. The result of the vote was clear: an overwhelming majority of German and Austrian voters (99 percent and 99.7 percent respectively) gave their retrospective approval to the “Anschluss”.

Sources

[1] Kurt Schuschnigg’s final radio address as Austrian chancellor, 11 March 1938; http://www.mediathek.at/atom/015C6FC2-2C9-0036F-00000D00-015B7F64 (last downloaded 12 February 2018).

[2] Paul Steiner’s diary, Paul Steiner Collection AR 25208, Box 1, Folder 7, http://www.lbi.org/digibaeck/results/?qtype=pid&term=476154 (last downloaded 12 February 2018).

Dr. Miriam BistrovicDr. Miriam Bistrovic is a historian and art historian. Since late 2013, she has headed the Berlin branch of the Leo-Baeck-Institute New York|Berlin, coordinating the organization’s activities in Germany. Her most recent project is the online calendar and the related touring exhibition, “1938Projekt – Posts from the Past”. |