What´s that for? Two Chemical Drawings by Marie Lavoisier

Nina Markert | 12 December 2024

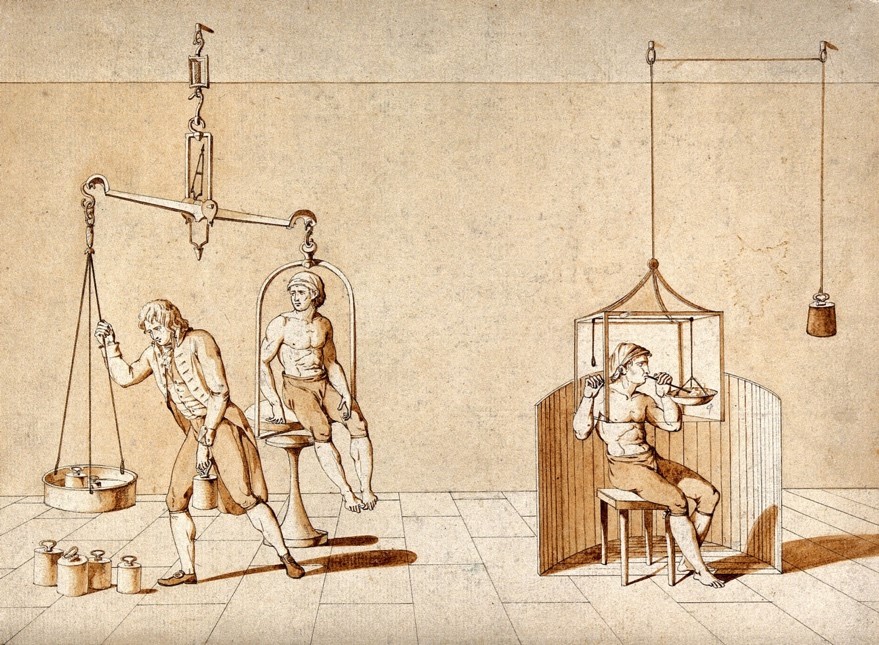

A bare-chested man sits in an oversized barrel and breathes through a tube. Three men are standing around him: one measures his pulse, another is occupied with the barrel, and a third speaks with a woman, who – equipped with pen and paper – appears to be documenting the event. Nina Markert, student assistant in the DHM department of special exhibitions, explains the story behind the scene.

If we think about chemical experiments, we envision people wearing laboratory smocks and safety glasses and busy with pipettes and test tubes. So it is hard to imagine that this drawing represents a chemical laboratory. Yet the picture shown here was part of an extensive series of experiments on human breathing carried out by the chemist Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743–1794) in the early 1790s with his younger colleague Armand-Jean François Seguin (1767–1835) in Paris. According to protocols, Seguin often served as the test person and can be identified here as the “man in the barrel”. The two persons facing each other are Lavoisier and his wife Marie.[i] Antoine Lavoisier had already made a name for himself by determining the role of the then newly discovered element oxygen in the process of combustion. In the course of precise and systematic measurements he also proved that the mass of materials in chemical reactions remains constant. He formulated the latter finding, known to this day as the law of conservation of mass, in 1789 in his main work Traité élémentaire de la chimie. With the system of nomenclature of chemical elements which he also described in his Traité, Antoine Lavoisier is considered the founder of modern chemistry.

Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier was the unofficial “manager” of the laboratory. As was normally the case with well-to-do women in the 18th century, access to education and science was opened primarily through experimenting in a home environment. After marrying Antoine Lavoisier – she was only 13 years old at the time – she was introduced to the work in the laboratory and learned English and Latin in order to be able to translate scientific treatises for her husband. His laboratory books are pervaded with her handwriting and detailed, true-to-scale sketches of experimental setups and instruments. In this way she contributed to the formulation, dissemination, and thus empirical verifiability of the experiments – a quality criterion that marks scientific works to this day.[ii]

The drawings from the 1790s shown here are ascribed to Marie Lavoisier. They attest to her artistic training but served in particular to illustrate her husband’s essays on respiration that were later published together under the title Mémoires de physique et chimie. However, the death of the chemist by guillotine in the turmoil of the Reign of Terror in 1794 and the subsequent conflict between Marie Lavoisier and Armand Seguin about copyright claims prevented an official publication of the book. In 1805, Marie finally circulated the work without acknowledgement of Seguin’s participation and without illustrations, which would have disclosed his cooperation.[iii] An exact description of the illustrations has therefore not come down to us and the precise process of the experiments remains obscure. The aim of the chemists – as far as can be deduced from other sources – was to develop a theory that would explain the process of respiration in a biological context. To this end they tried, among other things, to quantify the intake of oxygen and the emission of carbon dioxide during breathing. In the experiment, the latter occurred by direct exhalation into a bowl with a lime solution. The reaction of the solution with carbon dioxide produced calcium oxide, or lime, which could then be weighed. Seguin himself was weighed before and after every experiment in order to determine the amount of hydrogen that was depleted through breathing.[iv] Antoine Lavoisier and Seguin also determined that during breathing, physical exertion had an influence on the amount of hydrogen consumed and in the end on the combustion of nutrition, thus leading to questions in the field of biochemical metabolism.[v]

When the Lavoisiers were not working in the laboratory, they hosted a salon in which experiments and instruments were demonstrated and current theories discussed. The report of a guest from the year 1787 suggests that Marie Lavoisier was perceived as a “scientific lady”.[vi] Alongside tea and coffee, which were served in the salon, “her conversation on Mr. Kirwan’s Essay on Phlogiston, which she is translating from the English, and on other subjects, which a woman of understanding, that works with her husband in his laboratory, knows how to adorn, was the best repast.”[vii] From various references like this one we get an idea of the scientific work of women in the 18th century. Since the publications of Antoine Lavoisier do not mention the participation of his wife, her drawings take on a special importance. In them her contribution is documented for posterity.

After the death of her husband, Marie Lavoisier continued to organise the discussion and experiment evenings and managed the generous instrument collection, which is now preserved in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris. One of the precision scales that was used in Lavoisier’s laboratory between 1768 and 1789 can be seen until 6 April 2025 in the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century” in the Deutsches Historisches Museum.

[i] Cf. Marco Beretta, Imaging the Experiments on Respiration and Transpiration of Lavoisier and Seguin. Two Unknown Drawings by Madame Lavoisier, in: Nuncius 27 (2012), pp. 163–191, here: p. 188.

[ii] The reproducibility of experiments had practical limits: only a few science enthusiasts had the financial means to buy the expensive instruments. Antoine Lavoisier could only afford to carry out his experiments due to his work as royal tax collector.

[iii] Cf. Beretta,p. 191.

[iv] Cf. Ibid., p. 188.

[v] Vgl. Philipp Ball, Experimente. Die Chemie der Atmung, online article from 03.07.2024, URL: https://www.haupt.ch/magazin/natur/experimente/?srsltid=AfmBOoqTG-8N0ynOYmdiCEDIizO_ImAkWAhy87vV5IbiskxJhBH-0ZSd, Access: 11.11.2024.

[vi] Arthur Young, Travels During the Years 1787, 1788 and 1789, London 1792, p. 64f. Cit. from: Marco Beretta/Paolo Brenni, The Arsenal of Eighteenth-Century Chemistry. The Laboratories of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, Leiden/Boston 2022, p. 67.

[vii] Ibid. The essay by Richard Kirwan (1733–1812) deals with ideas that Lavoisier was able to refute through his experiments.

|

|

Nina MarkertNina Markert is a student assistant in the department of special exhibitions at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |