Friends of the Enlightenment

The Berlin Wednesday Society (1783–1798)

Stephanie von Steinsdorff | 5 February 2025

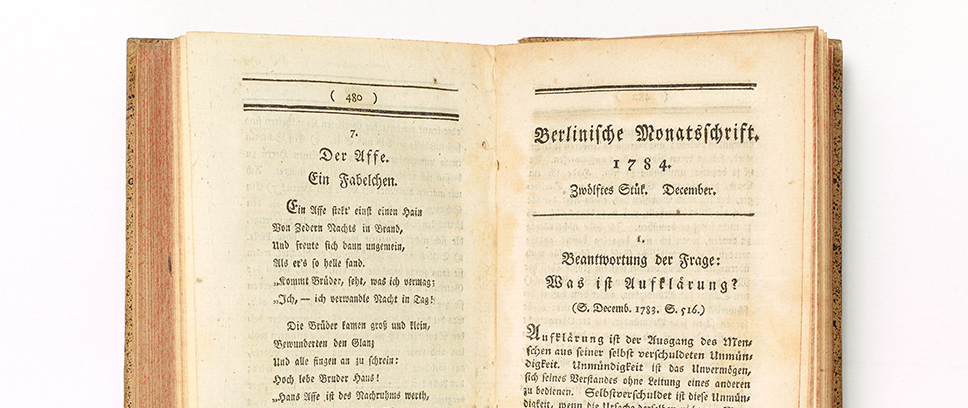

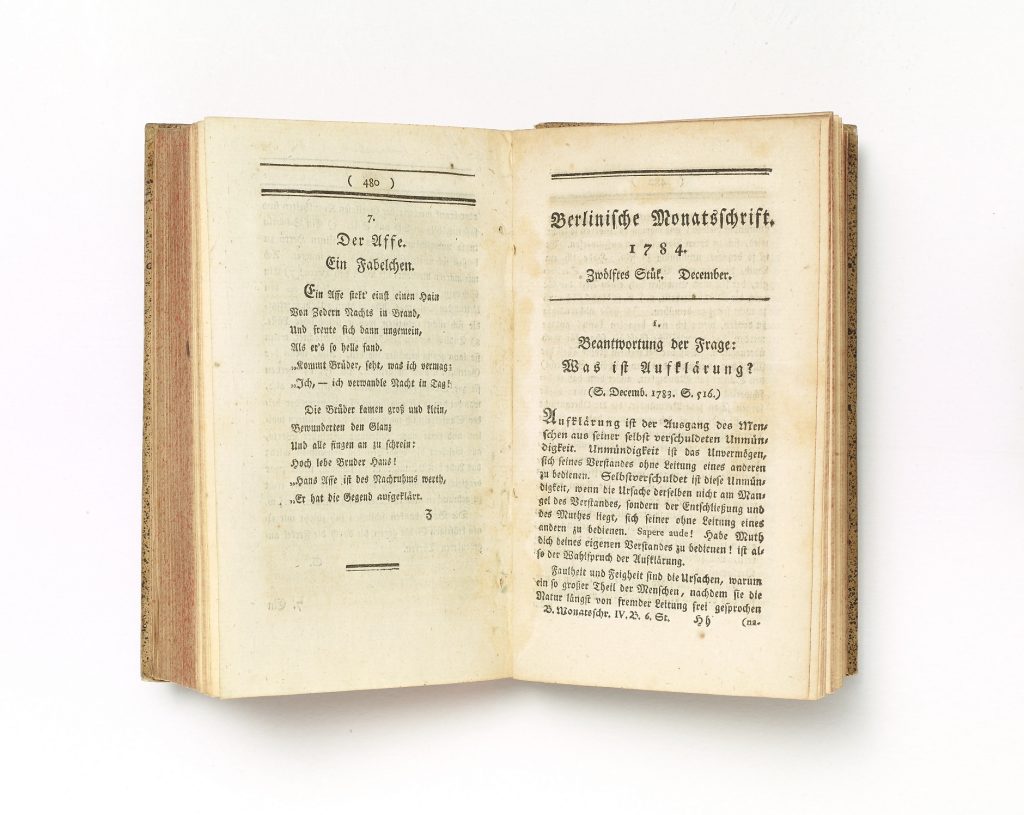

The question “What is Enlightenment?” not only provides the title for the exhibition in the DHM, but also inspired Kant’s famous response to the question, an original print of which can be seen in the museum until 6 April 2025. Kant published the essay in 1784 in the Berlinische Monatsschrift. The

monthly magazine was the mouthpiece of the Berlin Wednesday Society and enabled the public to participate in the questions that were discussed. Nearly all of the members of the Berlin Wednesday Society contributed regularly to the Berlinische Monatsschrift. But who was behind the Society and what did it contribute to the spread of the Enlightenment? Stephanie von Steinsdorff, research assistant, explores these questions in her article on the discussion series that takes its name from the Berlin Wednesday Society.

Collective thinking and discussing was their common path, “mutual and social enlightenment” their aim.[1] The members of the Society met once or twice a month at the home of one of the 24 permanent members. Among them were above all government ministers, professors, lawyers, publicists, pedagogues, philosophers, and theologians. Some names of the members are still known to us today, such as Christian Wilhelm von Dohm (1751–1820), who gained fame through his discussion of the equality of the Jews; the Berlin Enlightenment thinker, writer and book publisher Friedrich Nicolai (1733–1811); and Karl August von Struensee (1735–1804), a financial politician who carried on the enlightened social reforms initiated in Denmark by his younger brother Johann Friedrich Streunsee (1737–1772). The honorary member of the Society was among the best-known figures of the Berlin Enlightenment: Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786). Despite his widespread fame, Prussian King Friedrich II refused to let him, a Jew, become a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, although some of the Academy members supported his candidacy.[2] The Wednesday Society recognised Mendelssohn not only as a member, but insisted on giving him the status of honorary member, which can be understood as the Wednesday Society’s resistance to the royal order excluding him.

The members of the Society called themselves friends of “sound reason and common sense,”[3] but also as “Society of Friends of the Enlightenment,”[4] who wanted to converse with each other about sociopolitical topics in a protected room, thereby having self-enlightenment as their stated goal. In their discussions they should be “frank and brazen, but always unpretentious.”[5] The intimate circle also made it safe for them to carry on contentious conversations about uncomfortable topics.

“Here the members of the society were offered the opportunity to suggest a still undeveloped thought for discussion, ‘to submit it to the impartial assessment’ [of the friends], ‘to think more clearly about it and examine it from all sides’ and ‘through amicable exchange of thoughts (…) to mutually illuminate the intellect’.” [6]

Object of the discussions was “everything called knowledge and science,”[7] especially philosophical questions, whereby technical and practical discussions were to be avoided.[8] The discussions remained within the circle and were supposed to be kept secret in order to allow free discussion, because there was a “complete tolerance of all opinions, even those that appeared to be inconsistent.”[9]

The founding charter of 1783 regulated the procedure of the sessions: “[After] a preferably short lecture, a disciplined discussion should follow in which the participants […] should have their say. The gathering began at 6 pm, concluded with dinner together at 8 pm.”[10]

Today we would perhaps describe the Wednesday Society as a pre-political, but exclusive room for an active debate culture. To be sure, unlike tea parties and salons it was purely a circle of scholars in which only men active in public service took part. Marcus Herz took up the tradition of the Berlin Wednesday Society around 1800 when he began hosting a Wednesday Society oriented on scientific and academic topics, where women were likewise excluded. His emancipated wife Henriette Herz subsequently founded her own society, which she continued to host after the death of her husband. Unlike the Wednesday Society, non-academics and women discussed topics together with academics.

However, King Friedrich Wilhelm III saw in the original Berlin Wednesday Society a political, inflammatory influence in the spirit of the Enlightenment. Following the royal “Edict on the Prevention and Punishment of Secret Societies” from 20 October 1798, the Berlin Wednesday Society was forced to close itself down in the same year.

The eponymous discussion series in the DHM takes up this tradition and continues meeting every two weeks until 2 April 2025. Contrary to the original meetings, there is nothing secret about the DHM Wednesday Society gatherings, and all are welcome who are interested in discussing sociopolitical topics like peace, political maturity, revolution, and the constitutional state with experts.

[1] Günter Birtsch, “Die Berliner Mittwochsgesellschaft“, in: Formen der Geselligkeit in Nordwestdeutschland 1750 – 1820, (Ed.) P. Albrecht, H.-E. Bödecker, E. Hinrichs, Berlin 2003, Boston: Max Niemeyer Verlag, p. 424.

[2] Cf. Christoph Schulte, Von Moses bis Moses. Der jüdische Mendelssohn, Hannover 2020, Wehrhahn Verlag, p. 17.

[3] Tholuck quoted by Birgit Nehren, “Aufklärung – Geheimhaltung – Publizität. Moses Mendelssohn und die Berliner Mittwochsgesellschaft”, in: Moses Mendelssohn und die Kreise seiner Wirksamkeit, M. Albrecht, et al., (eds.), Berlin 1994, Boston: Max Niemeyer Verlag, p. 99.

[4] Birtsch, 2003, p. 423.

[5] Tholuck quoted by Nehren, 1994, p. 99.

[6] Nicolai, Ueber meine gelehrte Bildung, quoted from Nehren, p. 100.

[7] Tholuck quoted by Nehren, p. 99.

[8] Cf. Birtsch, p. 425.

[9] Tholuck quoted by Nehren, p. 99.

[10] Birtsch, p. 424.