Liberté, Égalité, Révolution! – The role of political liberty in the 18th century

Harriet Merrow | 26 February 2025

The Era of Enlightenment has many faces: Alongside experimental scientific findings and radical social changes that contributed to establishing a new bourgeois public sphere, its demands for equality and freedom led to the “Age of Revolutions”. Harriet Merrow, project assistant on the DHM exhibition “What is Enlightenment?”, examines its interrelationships on the basis of the struggles for liberty in an increasingly complex, geopolitical power structure.

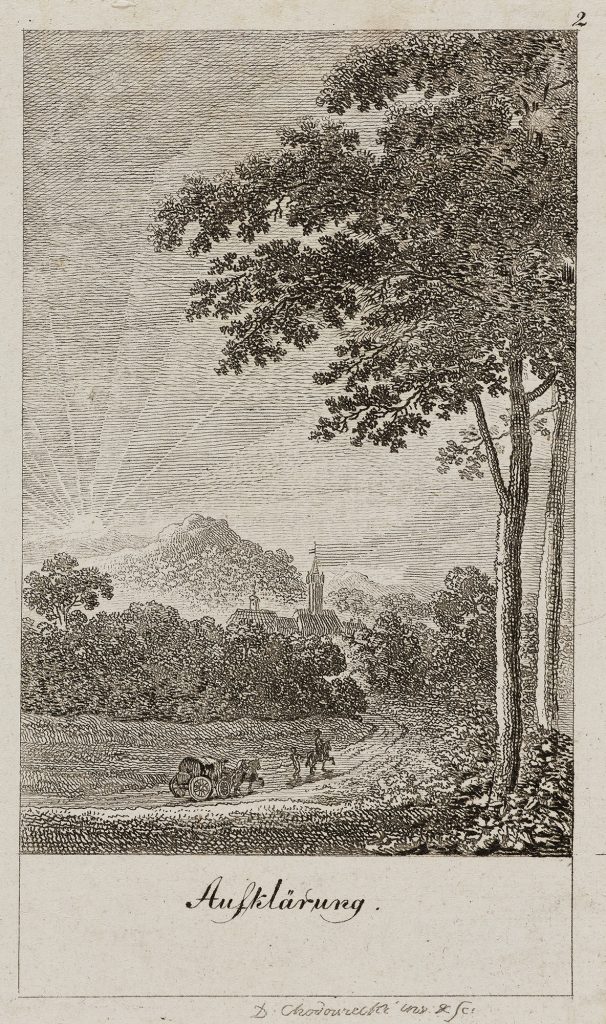

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, illustrator of the Enlightenment par excellence, shows an idyllic landscape with a rising sun that dispels the early morning mist. His allegorical etching “Enlightenment”, published in 1792, represents a meteorological metaphor for the “light of reason”. The print was widely disseminated and is not without reason the first object in the special exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the 18th Century”. It is an example of one of the many contributions to the clever self-stagings by advocates of Enlightenment, who used their illuminating metaphors to make it more difficult for their critics to raise objections.[i]

As it is, the peaceful picture stands in stark contrast to the then prevailing conditions in neighbouring France, where only two years earlier the revolutionaries had stormed the Bastille prison, the very symbol of rule, and not much later toppled the monarchs themselves. Although for contemporaries and the following generations the Enlightenment was marked above all by images of scholarly circles, bourgeois theatre and salons, the epoch was at least as much influenced by struggles for civil rights and political freedom.

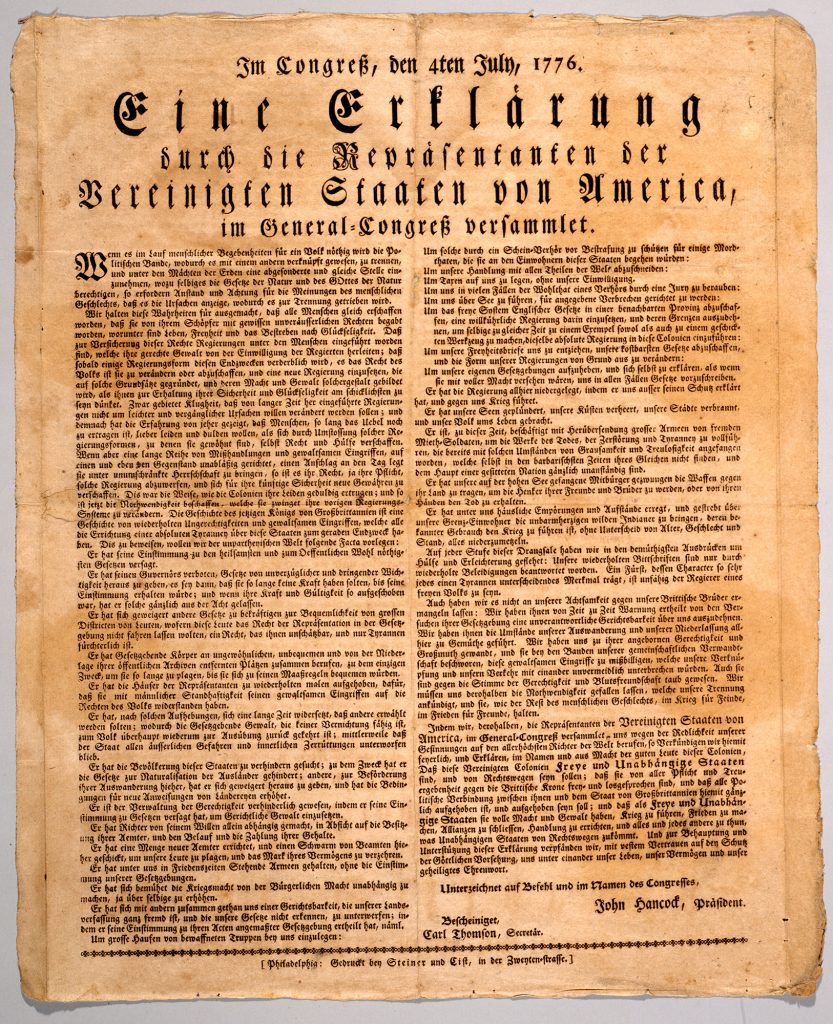

The arrest and later beheading of Louis XVI was no longer experienced by a prominent representative of the Enlightenment: more than a decade earlier, Boston-born Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), whose portrait bust is displayed alongside other important Enlightenment thinkers at the beginning of the exhibition, had had to do with the king. In the wake of the declaration of independence by the 13 British colonies on 4 July 1776, it was US Ambassador Franklin who, in 1778, had concluded the alliance between the USA and France in the Traité d’alliance franco-américaine – a highly risky political signal from Louis XVI to the British king, de facto a declaration of war.

The text of the Declaration of Independence accuses the British monarch, who is “unfit to be the ruler of a free people,” [ii] of being a tyrant, and describes the United States of America as a future democratic republic. Although the French king was aware of the dangers stemming from the enlightened demands of the revolutionaries for freedom and the ideals of equality if he officially recognised the USA, his rivalry with the British monarch finally outweighed all other arguments in the long-drawn-out decision-making process about the Treaty of Alliance of 1778.

The role of political liberty in the 18th century

In the Declaration of Independence, among whose authors Franklin numbered (but which was largely composed by Thomas Jefferson, later President of the USA), the central themes of the highly respected philosophers Montesquieu, Rousseau and Locke were reflected: Their sociopolitical concepts of natural law, the inherent equality of all people and the democratic organisation of the state clearly influenced the so-called “Founding Fathers” of the United States.

A German translation of the Declaration of Independence from Philadelphia is exhibited in “What is Enlightenment?“. Above it on the wall is a small handwritten excerpt from Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book, which lists the names of slaves who were forced to work on his estate Monticello. This juxtaposition here and in several other parts of the exhibition clearly shows that the idea of freedom and the equality of all people qua birth did not, in fact, apply to all people, but only to a privileged section of the (global) population.

Unlike the British “Glorious Revolution” of 1688/89 and the American Revolution of 1765–1783, the French Revolution marked a “dramatic caesura in the consciousness of its contemporaries.” [iii] The course of the revolution in France, which culminated in the grande terreur and a dictatorship, cast the demands of the Enlightenment thinkers for political liberty and their theories on the equality of all people in an unfavourable light. Moreover, the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” from 1789 also had to defend itself against the accusation that it contained “blind spots” and even the intentional exclusion of certain sections of the population. Thus it happened that the illegitimate daughter of a washerwoman came to Paris as a young widow, joined the Revolution, and published her feminist reinterpretation, namely the “Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen”. With her indefatigable fighting spirit, Olympe de Gouges achieved demonstrable improvements in the treatment of women in the French state,[iv] but due to her arrest and subsequent execution experienced little of it herself.

That much on the epoch of Reason – it was multifaceted and contradictory like few other eras. On the one hand, the century brought forth a feminist icon like de Gouges who placed her ability to read and write in the service of the struggle for equal rights of the sexes.[v] On the other hand, she paid for it with her life.

[i] Cf. Fulda, Daniel: „Zur Klärung eines Begriffs, der Vorgriff und Rückgriff zugleich ist“, in: Raphael Gross und Liliane Weissberg (eds.): Was ist Aufklärung? Fragen an das 18. Jahrhundert. Berlin 2024: p. 31.

[ii] Declaration of Independence.

[iii] Meyer, Annette: Die Epoche der Aufklärung, 2. Aufl. Berlin 2018: p. 205.

[iv] Cf. Kuhn, Axel: Die Französische Revolution, Stuttgart 2011: pp. 84-85.

[v] Cf. Stokowski, Margarete: „Freiheit, Gleichheit, Gerechtigkeit“, in: De Gouges, Olympe: Die Rechte der Frau und andere Texte: Stuttgart 2022, pp. 70-78: p. 73.

|

|

Harriet MerrowHarriet Merrow is the project assistant at the Deutsches Historisches Museum for the exhibition “What is Enlightenment? Questions for the Eighteenth Century”. |