Private and Public Collecting

The library of Imperial Count Joachim von Ortenburg and the collecting practice of the library of the Deutsches Historisches Museum

Dr Matthias Miller | 12 March 2025

The blog series on the collection work of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM) deals with core questions such as the decision for or against the acquisition of certain objects, the different ways in which they are found and acquired, the changing research questions posed by the objects in the collections, the provenance and origin of the objects, and many other aspects.

The DHM library collects and preserves works that are of key importance for an understanding of German history and culture. Matthias Miller, head of the library, explains the practice of collecting for the DHM library on the basis of a selected example.

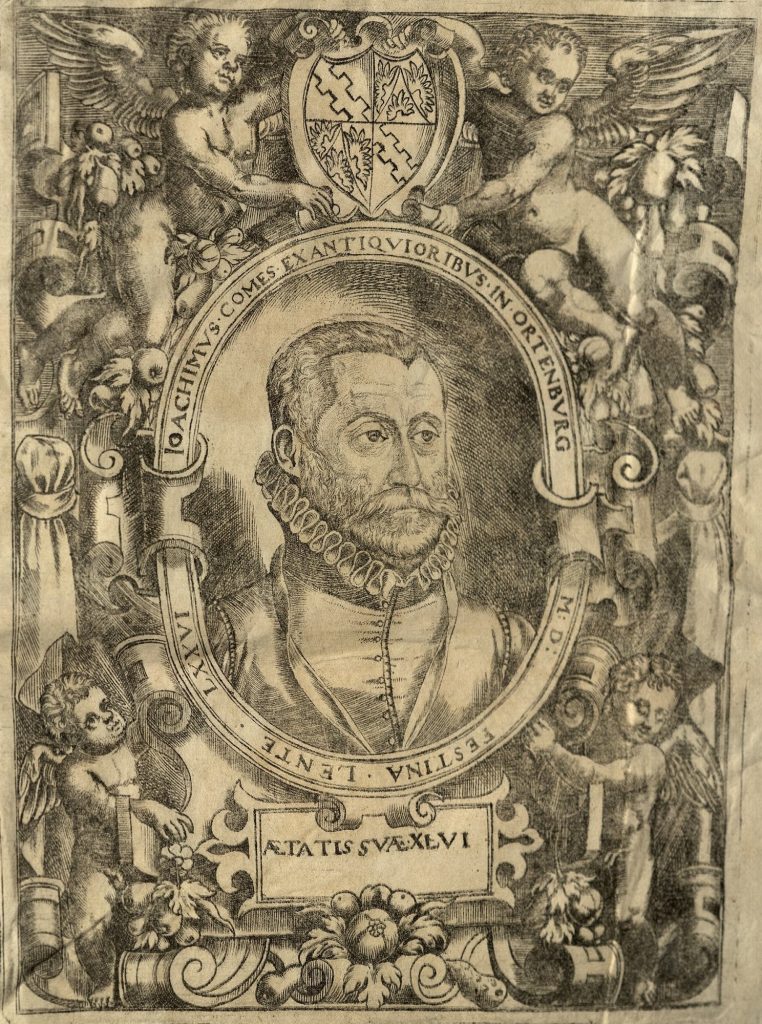

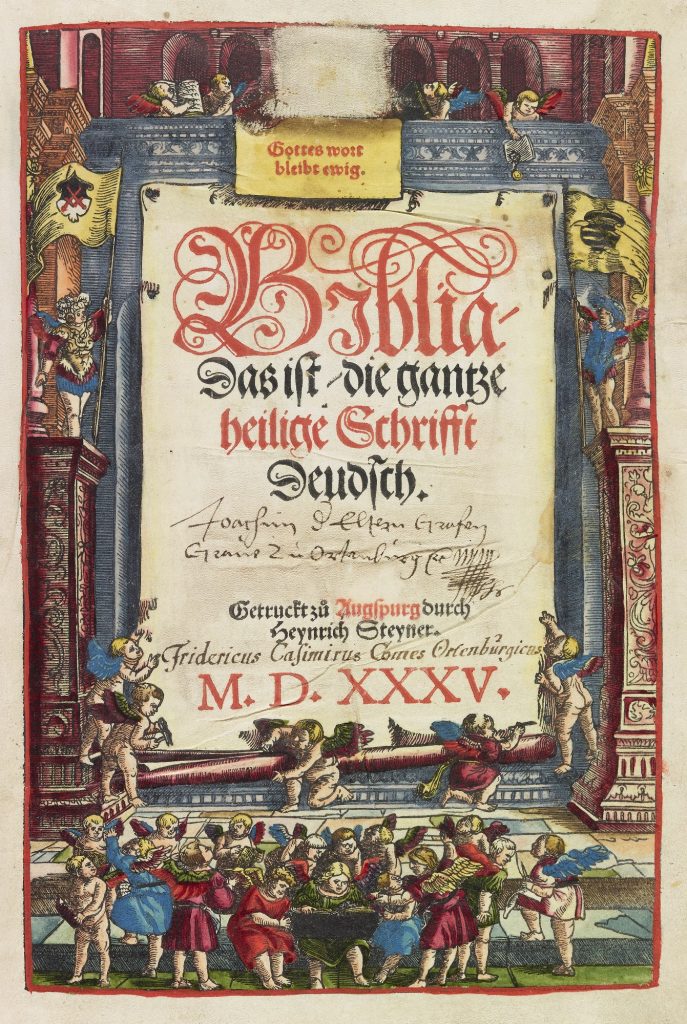

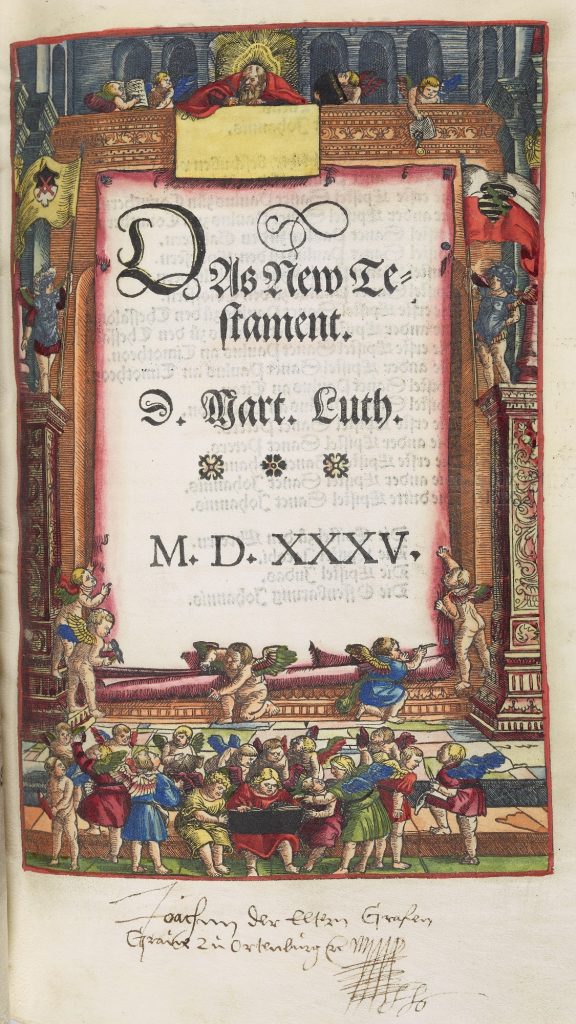

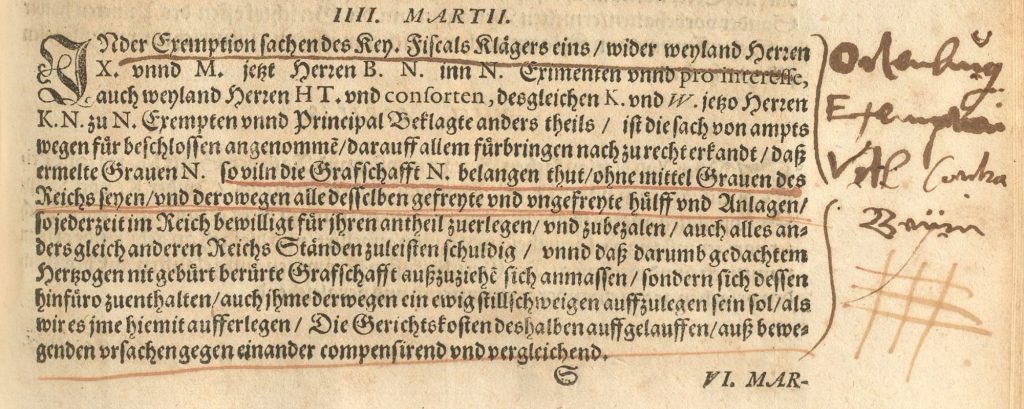

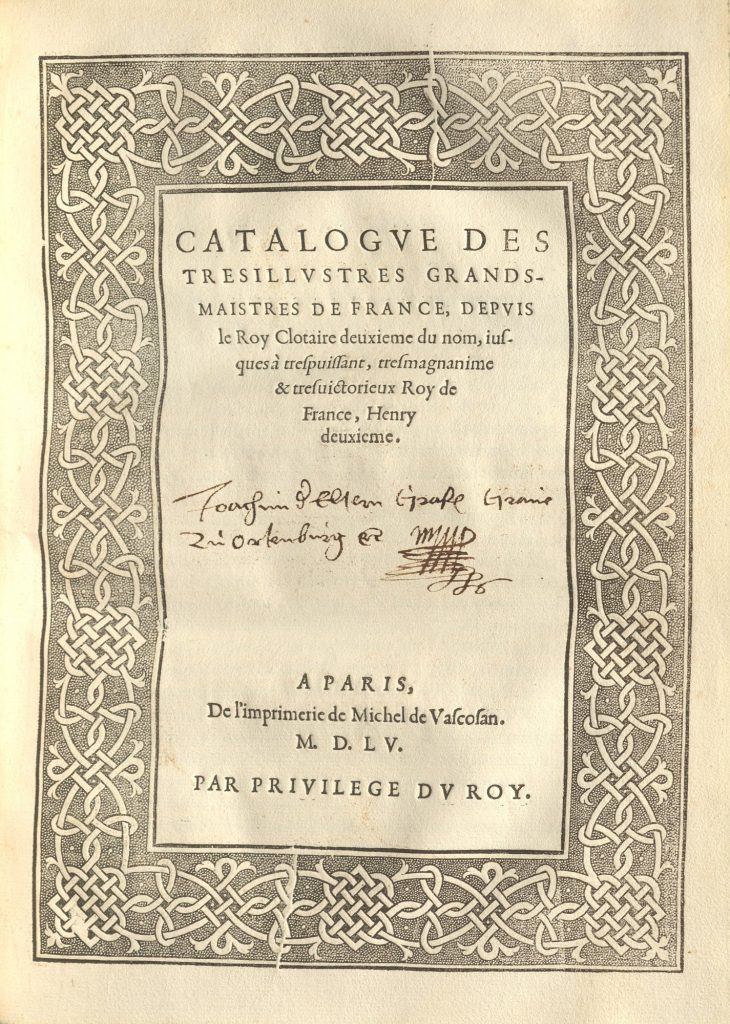

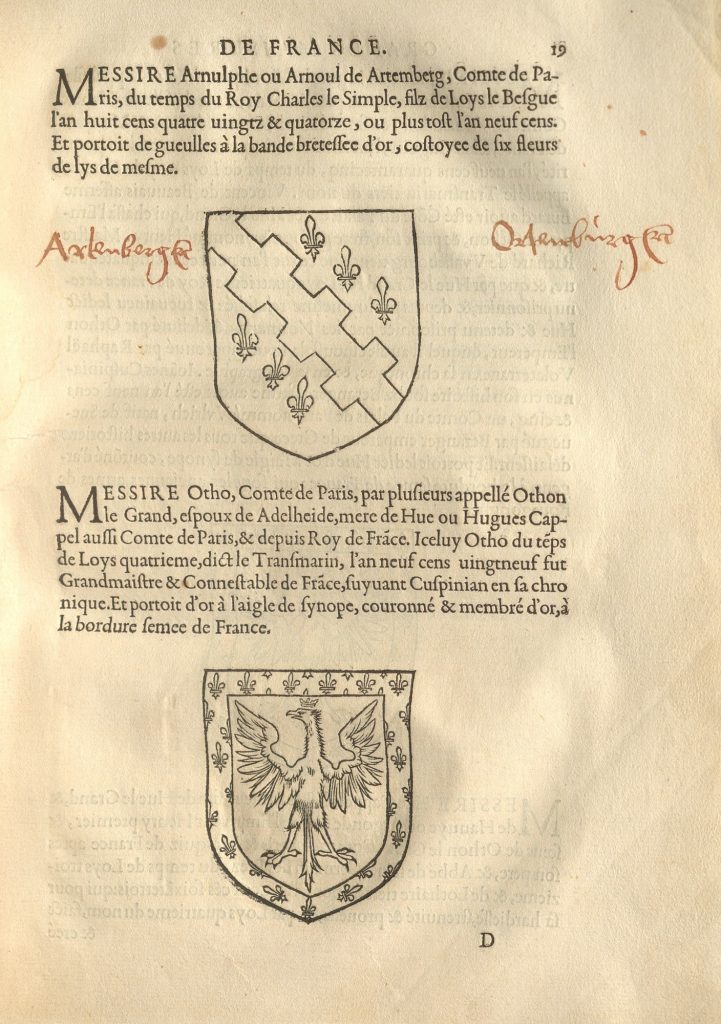

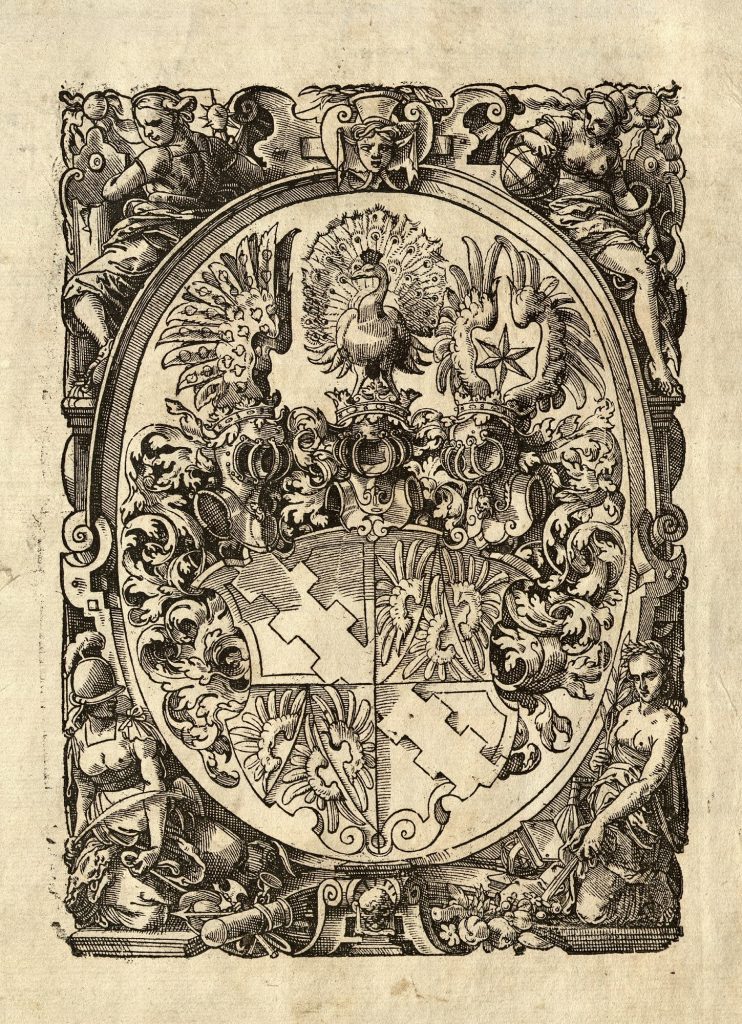

The Lower Bavarian Imperial Count Joachim von Ortenburg (1530–1600) was a passionate collector of books. When he died childless on 19 March 1600, he left behind a large library consisting of some 550–600 volumes. At first there were books he needed for his studies in Ingolstadt from 1543 to 1545. Then he acquired works for his law studies (1545–1548) in Padua, and later books related to his family history, history in general, and theology. As a humanistically educated nobleman he was undaunted by Latin or Greek texts. His collection of books always had a purpose. From his father he “inherited” a lawsuit before the Imperial Chamber Court that had been smouldering since 1549, concerning the question of the imperial immediacy of the duchy of Ortenburg, namely, whether Ortenburg was directly subordinated to the Emperor or first indirectly to the dukes of Bavaria. In addition, Joachim von Ortenburg was concerned with tracing his family history back to the so-called ancient nobility, i.e., the noble dynasties that formed part of the aristocracy as of 1400 at the latest. To prove his case, Joachim von Ortenburg undertook extensive research into his family background, which caused him to acquire a book about the French “grands maîtres” from 1555 in which his reputed ancestor Arnulphe de Artemberg, Duc de Paris around the year 900, is mentioned next to an illustration of his coat-of-arms. Ortenburg’s primary interest, however, was religion. Probably influenced by his brother-in-law Ulrich Fugger, Joachim von Ortenburg converted to Protestantism in 1563 and, according to the legal principle introduced in the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 known as cuius regio, eius religio – whose realm, his religion –, established this faith in his little duchy, which of course was considered an affront by the Dukes of Bavaria. A gift from Ulrich Fugger in the year 1561, a splendid two-volume Bible in Martin Luther’s translation, printed on parchment in Augsburg by Heinrich Steiner in 1534, might have been the catalyst for the change of confessions two years later (DHM-Bibliothek, RA 92/2968 -1 und RA 92/2968 -2). [Abb. 2,1 und 2,2] We know all this – alongside archival sources – from records of ownership and other marginalia in the books of Joachim von Ortenburg that have been preserved since 1600. For him personally, collecting books not only had political, religious and genealogical purposes, but the works also served him as strategic instruments in the conflicts of the time.

Today, centuries after his death, the library of the DHM is attempting to reconstruct the valuable works of his collection, which were widely scattered as a result of an auction in 1999, and to restore them not only virtually, but also to acquire the books themselves, insofar as they fit into the profile of our collection. This raises questions as to how book collecting then – in the 16th century – can be seen in comparison to the modern efforts of the DHM to bring together and preserve historical collections.

According to Manfred Sommer (Sammeln. Ein philosophischer Versuch, Frankfurt/Main, 1999), collecting can be divided into two categories: economical collecting (with later disappearance), like collecting mushrooms, and aesthetic collecting (with the aim of permanently retaining the objects), such as paintings. Both collections have in common that they want to be shown: the mushrooms before they are cooked as an expression of finder’s luck, the pictures on one’s own walls as an expression of one’s knowledge of art. But in which of these areas do books belong? Are they objects of economical or of aesthetic collecting? Do they want to be shown or should they only stand in the bookcase with the spine of the books visible. And what kind of collecting is the task of a museum’s library like that of the DHM?

While Joachim von Ortenburg’s collecting practices in the 16th century were strongly influenced by his political and religious aims, the library of the DHM has an approach oriented on history and culture. The DHM is the central history museum in Germany and the main concern of its library is academic research and cultural education. The DHM library collects and preserves works that are of central importance to our understanding of German history and culture. As noted, it is the ongoing effort of the DHM library to bring together the scattered books of Joachim von Ortenburg’s library, either virtually or in kind. This task is an exciting challenge because the books that are now widely dispersed represent not only an important part of cultural heritage, but also form a bridge between the collection practice of the 16th century and the modern work of a museum.

From a professional point of view, i.e., the perspective of those whose job it is to care for and expand a collection of books on German history, the collecting as well as the non-acquisition of books covering such a large area as German history represent enormous challenges, precisely because there are no limitations as to content, time or form. It is therefore necessary to specialise in certain areas, especially because book collecting is also faced with financial limitations – not only the actual acquisition, but also inventorisation and indexing cost money, not to mention the ecological hurdles: books have to be transported, stored, and air-conditioned for long periods of time, and often restored, all of which requires further funding.

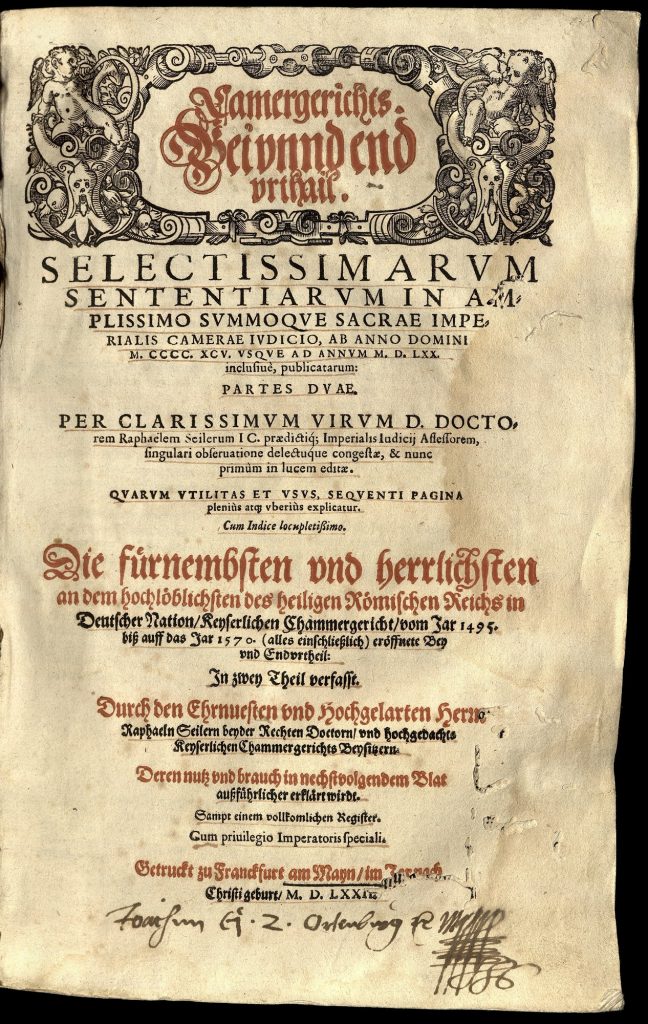

But when it is sensible and doable, objects of suitable and important origin, contents, or form will continue to be added to the library collection. And thus in 1992, the above-mentioned Ortenburg Bible entered the collection of the DHM library and formed the beginning of a small special collection within the large book collection of the DHM. At the above-noted auction in 1999, the DHM was able to purchase a further book from the Ortenburg library. [Abb. 3,1 und 3,2] In keeping with the selective collecting, discarding, and adding new or different works, the cycle of privately owned books and those in the book trade repeats itself every 20 or 30 years. This has to do with the duration of a generation and the dissolution of collections after the death of the collector. Since books from the Ortenburg library tend to show up in the book trade after about 25 years, the DHM tries to purchase them (when the price is acceptable). For the books also reveal new aspects of the life and times of Joachim von Ortenburg, the original collector. A striking thing about his books are the numerous notations of ownership, underlinings and marginalia, for Joachim von Ortenburg always had quill in hand when he read them, and he immortalised himself in this way. Meanwhile, the DHM owns twenty titles from his library, including the purchase in 2024 of the Catalogue des tres illustres Grandsmaistres de France by Jehan Le Féron (Paris: Michel de Vascosan, 1555; DHM-Bibliothek, RA 2024/12), in which Joachim von Ortenburg discovered his early ancestor Arnulphe de Artemburg with the Ortenburg coat-of-arms and noted it in the book. [Abb. 4,1 und 4,2]

While Joachim von Ortenburg always saw his collection as a personal resource which he actively cared for and utilised, collecting and preserving in the DHM is now carried out from the standpoint of cultural heritage and historical preservation. The re-assembling of the scattered works of Ortenburg’s collection by the DHM illustrates the modern approach of “active collecting”: Instead of viewing individual collected objects merely as private possessions, greater importance is now laid on reconstructing and preserving historical collections in order to make the cultural heritage available to a broader public.

To this end the DHM pursues a laborious and often complex procedure that aims not only to acquire books, but also to reunite and preserve a historical collection that was torn apart by auctions and private sales. The collecting of books is thus marked by an institutional interest that aims to preserve knowledge and to secure for coming generations the historical significance of collections and their provenance in the context of the history of Germany. Joachim von Ortenburg’s library was a private and exclusive space where access and use were limited to the Count, his family and his closest advisors. In our time, libraries like that of the DHM are open to the public and serve the academic and cultural education of society. The attempt by the DHM to reconstruct the collection of Joachim von Ortenburg is thus a step towards broader accessibility and the sharing of the cultural heritage. In this sense, aesthetic collecting of books also contributes to public display and exhibition. [Abb. 5]

The library of the Deutsches Historisches Museum

Entrance: Hinter dem Giesshaus 3, 10117 Berlin

Mon–Thu 9 am – 4 pm, Fr 9 am – 1 pm

|

© DHM/Thomas Bruns |

Matthias MillerMatthias Miller is Keeper of the Library – Curator of Manuscripts Old and Valuable Books at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. |