![[Translate to English:] Hannah Arendt und das 20. Jahrhundert [Translate to English:] Hannah Arendt und das 20. Jahrhundert](/assets/_processed_/5/d/csm_HA_Slider_neueWebsite_b051b002e4.jpg)

Hannah Arendt and the Twentieth Century

The twentieth century simply cannot be understood without Hannah Arendt, wrote the author Amos Elon. Arendt significantly influenced two concepts that are essential for the understanding of the twentieth century: “totalitarianism” and the “banality of evil”. Arendt’s insights were rarely left unchallenged.

The exhibition “Hannah Arendt and the Twentieth Century” aims to trace Arendt’s observations on contemporary history and introduce to the public a life and work that mirrors the history of the twentieth century: totalitarianism, anti-Semitism, the situation of refugees, the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, the political system and the racial segregation in the U. S., the student movement and feminism. Arendt frequently expressed her views on current events as a public intellectual, often sparking fierce controversy.

As the exhibition will show this diagnostic appraisal makes the question of the power of judgement particularly urgent today against the backdrop of pluralization, the accelerated change in values and growing populism.

At the start of the exhibition “Hannah Arendt and the Twentieth Century”. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Arendt's Reflections on Rahel Varnhagen: Growing antisemitism in Germany led Hannah Arendt to turn from philosophy to politics in the late 1920s. She decided to write a biography of Rahel Varnhagen, a Jewish woman who held a cultural salon in the time of Goethe. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Arendt's Reflections on Rahel Varnhagen: Salon ensemble from the Romantic period with portraits of Rahel Varnhagen's famous guests, including Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt, Bettina von Arnim and Heinrich Heine. Around 1800, people met in salons to exchange views on art, politics and science, regardless of their origin, social class, sex, or religion. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Arendt's Reflections on Rahel Varnhagen: The life of Rahel Varnhagen was generally seen as an example of successful emancipation. Arendt, however, took a different view. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Zionism: 'For vengeance and redemption!' Poster for the Jewish Brigade, a special unit of the British Army. In 1941, Hannah Arendt managed to flee via Lisbon to New York. There she wrote about current issues connected with Zionism. In the German-Jewish emigrant magazine 'Aufbau' she called for the creation of a Jewish army that would fight with the Allies against Hitler. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

Zionism: The exhibition shows documents relating to Arendt's column in 'Aufbau' as well as objects that Arendt's friend, the religious philosopher Hans Jonas, kept from his time in the Jewish Brigade. After the war, Arendt’s relationship to Zionism became more distanced. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Totalitarian Rule: Model of Crematorium II, Auschwitz-Birkenau. Between 1940 and 1945, European Jews, Poles, Sinti and Roma were murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. The majority of them were killed with the poison Zyklon B. The Polish sculptor Mieczysław Stobierski made this model for the Deutsches Historisches Museum in 1994–95. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Totalitarian Rule: Hannah Arendt's treatise 'The Origins of Totalitarianism' was published in 1951. In it, she described the concentration and extermination camps set up by the Nazis as the most logical consequence of totalitarian rule. There they had tested, as if in a laboratory, how to achieve total domination over individuals. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil: Hannah Arendt during the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem. In 1961, Hannah Arendt went to report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, who had been responsible for deporting millions of Jews. Arendt's report was published in 1963. With her description of Eichmann as 'banal' and her remarks about the so-called Jewish Councils instated by the Nazis, she sparked a fierce debate. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. (JCR): In 1949, Hannah Arendt became the executive secretary of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. in New York. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. (JCR): The organisation’s mission was to trace cultural goods stolen by the Nazis and transfer them to the US or Israel. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Hannah Arendt's Compensation Claim: In 1966, Arendt filed a complaint with Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court. It concerned her claim to a civil service pension: having to flee Germany in 1933 had prevented her from completing the professorial teaching qualification (habilitation) with her postdoc thesis on Rahel Varnhagen. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

The court decided to recognise the thesis by itself as equivalent to habilitation. The exhibition presents extracts from her case file to the general public for the first time. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

American Citizen: Arendt was granted American citizenship in 1951. For her, this was no mere formality, because she saw the United States as the most politically free country in the world. She taught at several universities, including the University of Chicago and the Wesleyan University, as shown here. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

'Reflections on Little Rock': In the mid-1950s, the United States Supreme Court abolished racial segregation in public schools. After a white crowd hindered black pupils from attending school, the U.S. government sent federal troops to escort them safely into the school. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

'Reflections on Little Rock': Most intellectuals welcomed this measure. Not so Hannah Arendt. In her article 'Reflections on Little Rock', she criticised the authorities for intervening. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

'The Hungarian Revolution' 1956: 'If there ever was such a thing as Rosa Luxemburg's "spontaneous revolution" – it was this sudden uprising of an oppressed people for the sake of freedom and hardly anything else ... we had the privilege to witness it.' Hannah Arendt on the popular uprising in Hungary. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

The International Student Movement: Placard: 'Nous sommes tous '"indésirables"' [We are all 'persona non grata'] Placard from the French student movement, protesting at the expulsion of Daniel Cohn-Bendit from France. Hanna Arendt welcomed the student protests of the 1960s in the United States as a renewal of interest in politics. She also expressed sympathy for the protestors of May '68 in Paris, and for one leading figure in particular: Daniel Cohn-Bendit, whose parents had been friends of hers during the period of exile in Paris. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

The International Student Movement: Arendt took a more critical view of the student movement in Germany, which she saw as dogmatic and bogged down in theory. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Donation from Edna Brocke: Thanks to a generous donation to the Deutsches Historisches Museum from Edna Brocke, Hannah Arendt's grandniece, the exhibition is able to present many of Arendt's personal belongings, including jewellery, an elegant fur cape, a cigarette case and her briefcase with the monogram H.A.B., standing for Hannah Arendt-Blücher. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

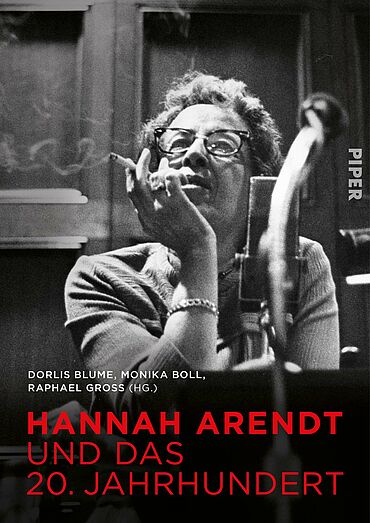

Fred Stein photographs Hannah Arendt. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Minox Camera: In May 1961, Hannah Arendt bought a miniature camera of the Minox brand. From then on, she was seldom without the Minox, whether travelling or at home. She photographed relatives and friends in Israel, New York and Europe. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Friendships: Arendt kept up intense friendships, forming a kind of safety net over the voids left by flight and displacement. Photo © DHM/Gregor Baron

Friendships: A complementary presentation introducing her friends appears at the relevant places in the exhibition. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Friendships: Among them were Karl Jaspers, Mary McCarthy, Martin Heidegger, Heinrich Blücher, Walter Benjamin, Anne Weil, Hans Jonas, Günther Anders, Edna Brocke, Lotte Köhler and Wystan H. Auden. Photo © DHM/Thomas Bruns

Audio guide

in English and German

€ 3 plus admission