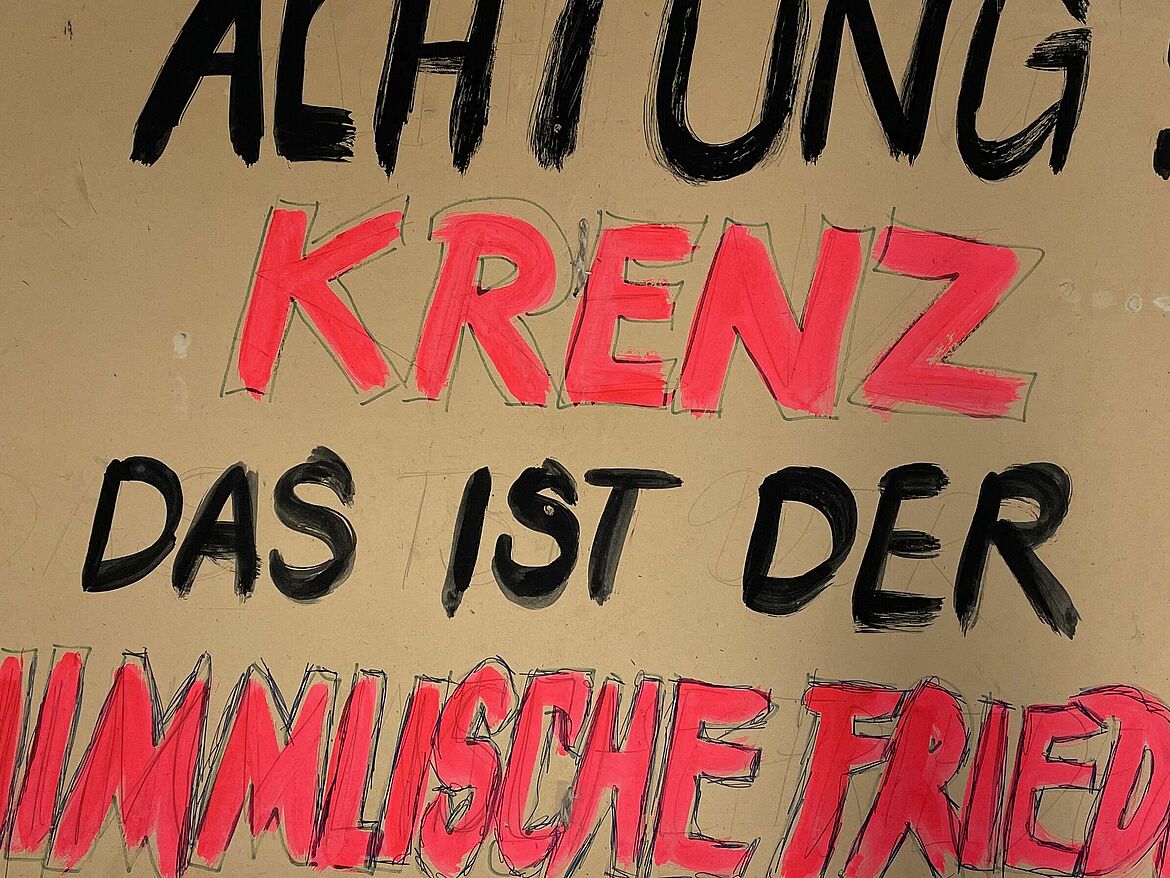

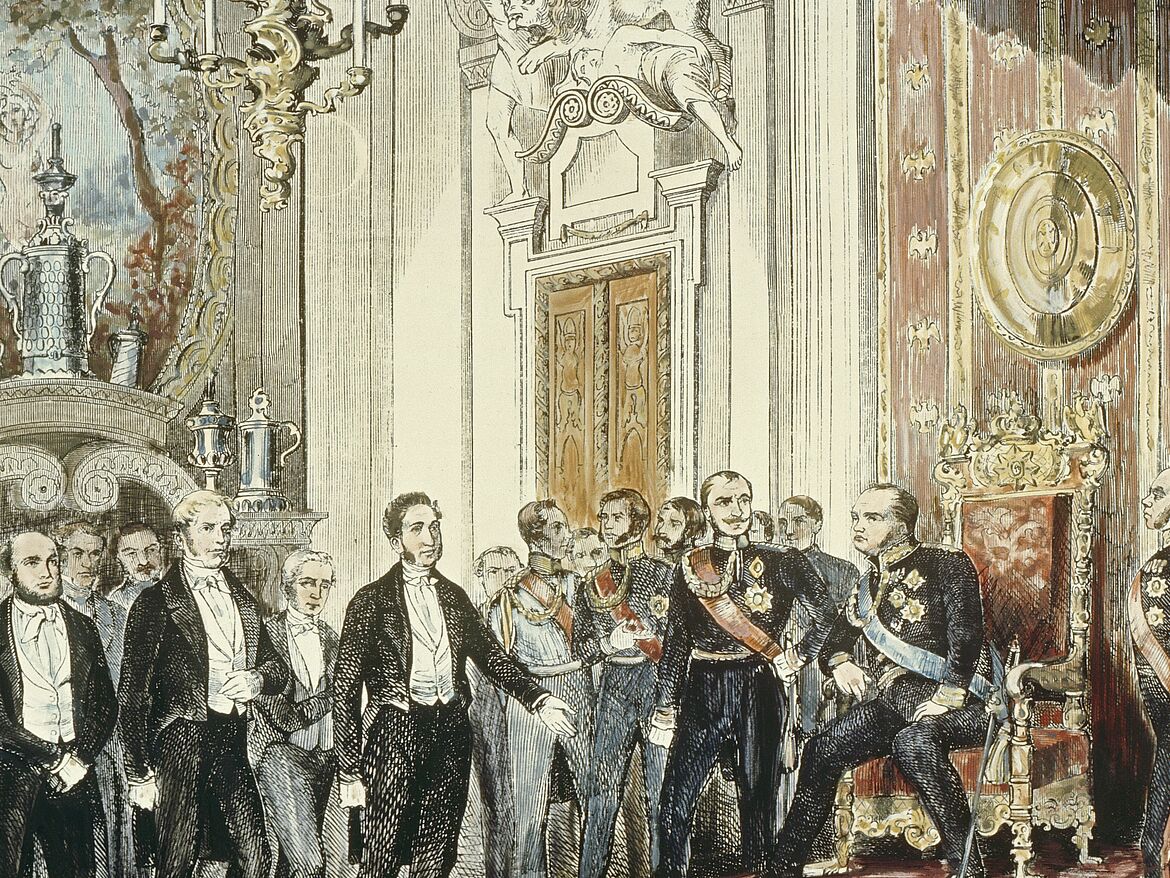

Along a string of 14 important dates in German history, “Roads not Taken” takes a look back(wards) at decisive historical events from 1989 to 1848. The turning points that actually happened are then confronted with possible courses of history that did not take place – without attempting to present an alternative or counterfactual narrative of history. Instead, the exhibition, based on an idea by the historian Dan Diner, is about how likely it is that a development inherent to the occurrence could have sent it off in a different direction. The project manager is Fritz Backhaus; the curatorial team consists of Julia Franke, Stefan Paul-Jacobs, and Dr. Lili Reyels.