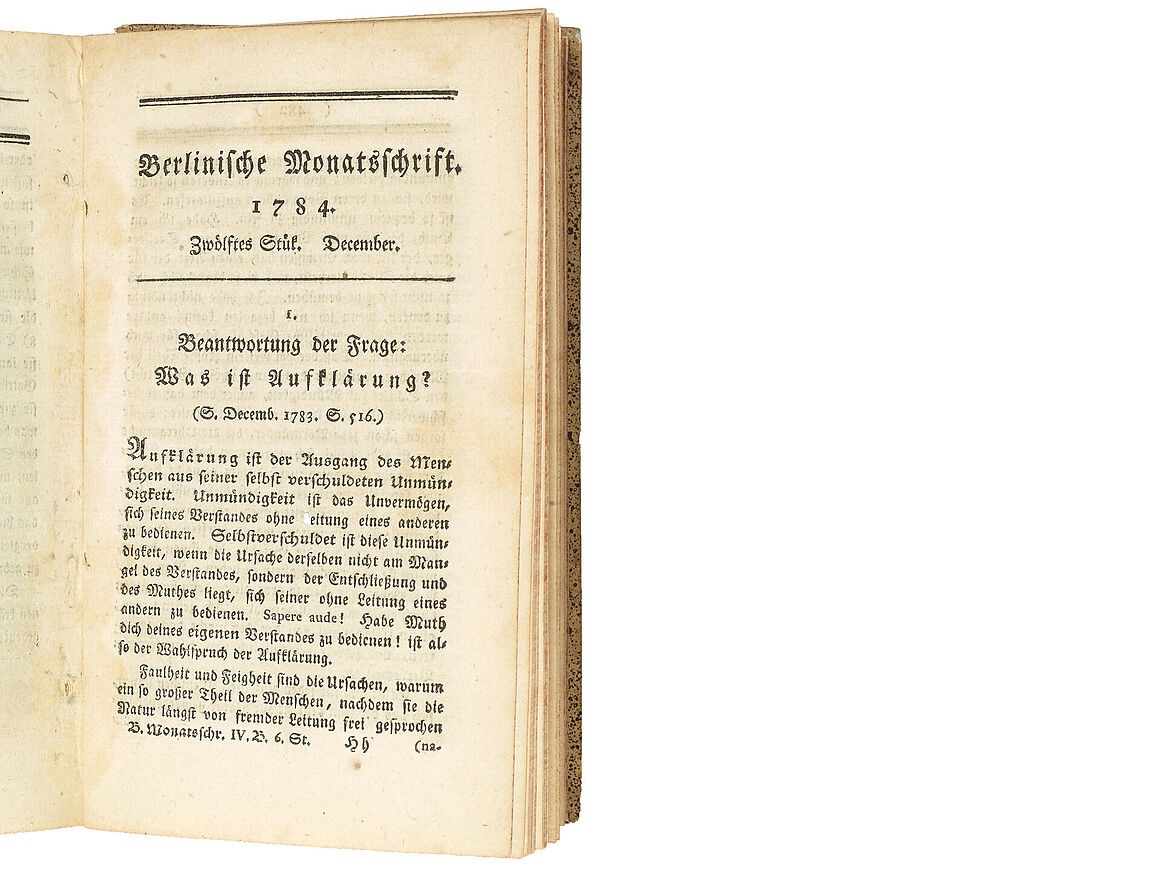

The exhibition examines the question “What is Enlightenment?”, which was first posed in 1783 in the magazine Berlinische Monatsschrift, and concentrates on the important debates of the epoch, including the contradictions and ambivalences that surrounded the discussions. From an international perspective it focuses on some of the main topics of the 18th century such as the search for knowledge and the new science, the order of the world as well as statesmanship and political liberty.

Title page of Immanuel Kant’s essay “Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?”, in: Berlinische Monatsschrift, Berlin, 1784 © DHM